The Algorithmic Image: In Conversation with Karthik KG

Karthik KG is an artist and researcher whose practice enquires the algorithmic culture and mnemonic infrastructures in contemporary societies. His works often explore the everyday use of digital technologies, new modes of knowledge production and the shaping of digital subjectivities. In this two-part conversation, we delve into his process and consider the implications of algorithmic culture on contemporary image making.

AB: Tell us a little bit about your background. Since engaging in multi-disciplinary modes—as an artist, curator, researcher and technologist—what has been your trajectory, and how do you frame your own practice today?

KK: Encountering a new form or thought process, or approaching through different disciplines comes with its own challenges; simultaneously, there is an uncanny pleasure in exploring the newer possibilities they offer, and this is what primarily shapes my practice. I grew up enjoying doodling and making things like paper sculptures, etc., and later the world of computer had a new materiality to offer. Since then, creating graphics, moving images and other coding practices has been a fascination. My formal training in Engineering, Visual Arts and Curatorial Research added more tools to my practice, be it research work or a text or origami or algorithmic procedures or generative animations. These shifts, especially the role of technology that is at play in shaping our everyday experience, form the core of the exploration, and all the resulting works are attempts at a “diagram” of this flux.

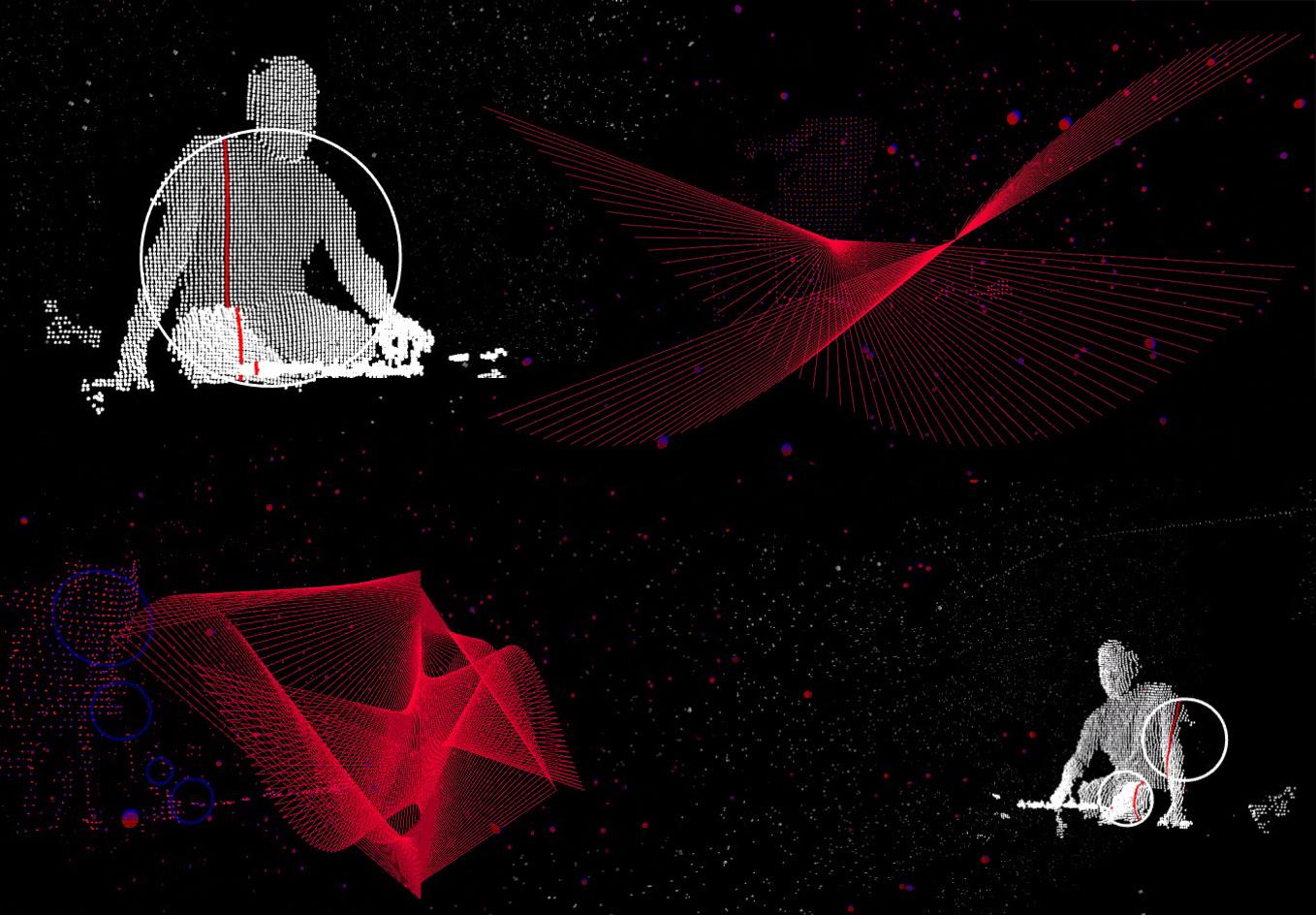

Still from Surveying an Invisible Soundscape, Live Act, 2015.

AB: In multiple projects, for instance Talking Heads, you deal with a kind of algorithmic image making, which seems to change the status and framework of visual images at large. Could you reflect on this a little? How are images made by, for and with algorithms different from the photographic, realist or representational kinds of image making?

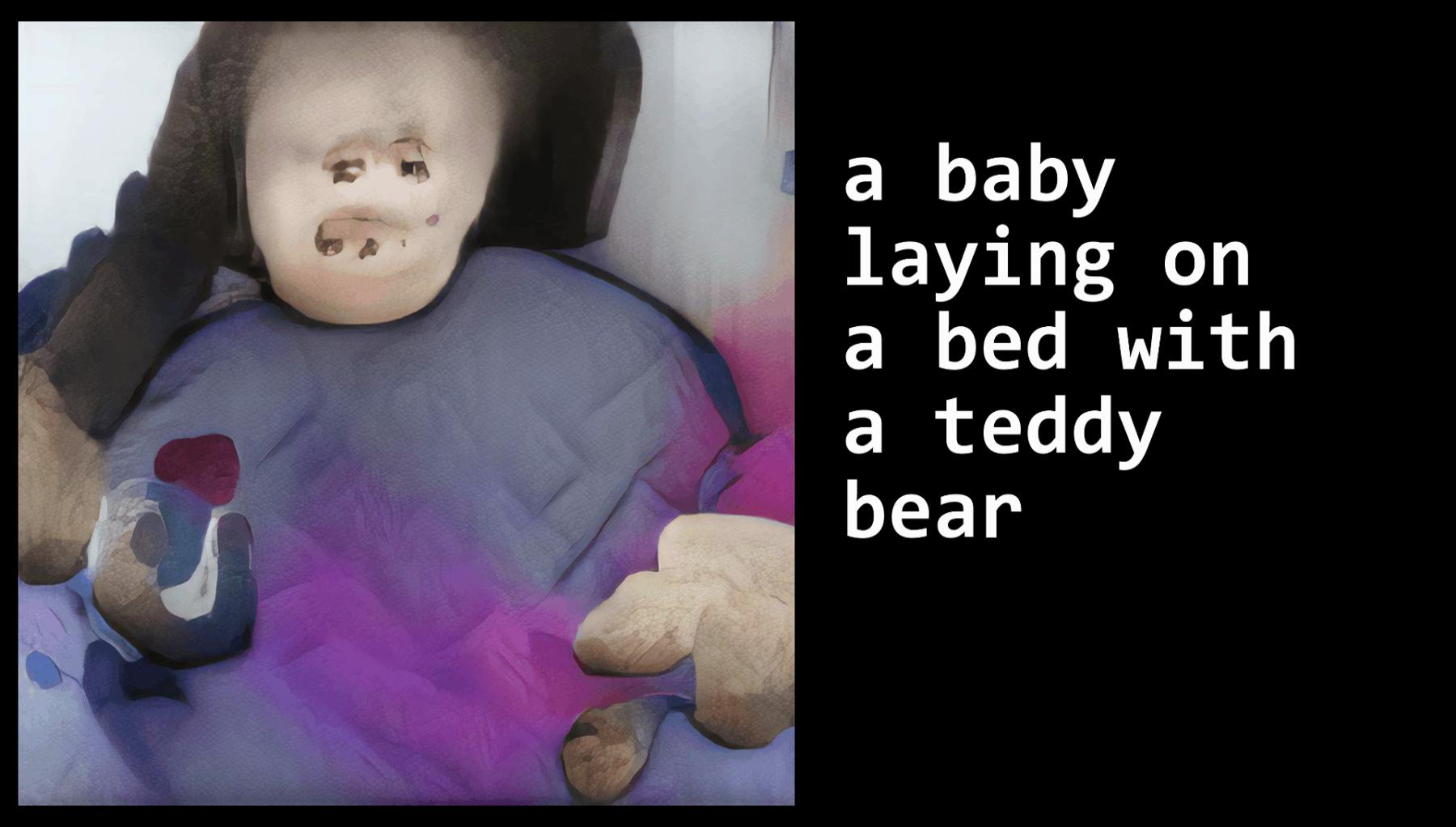

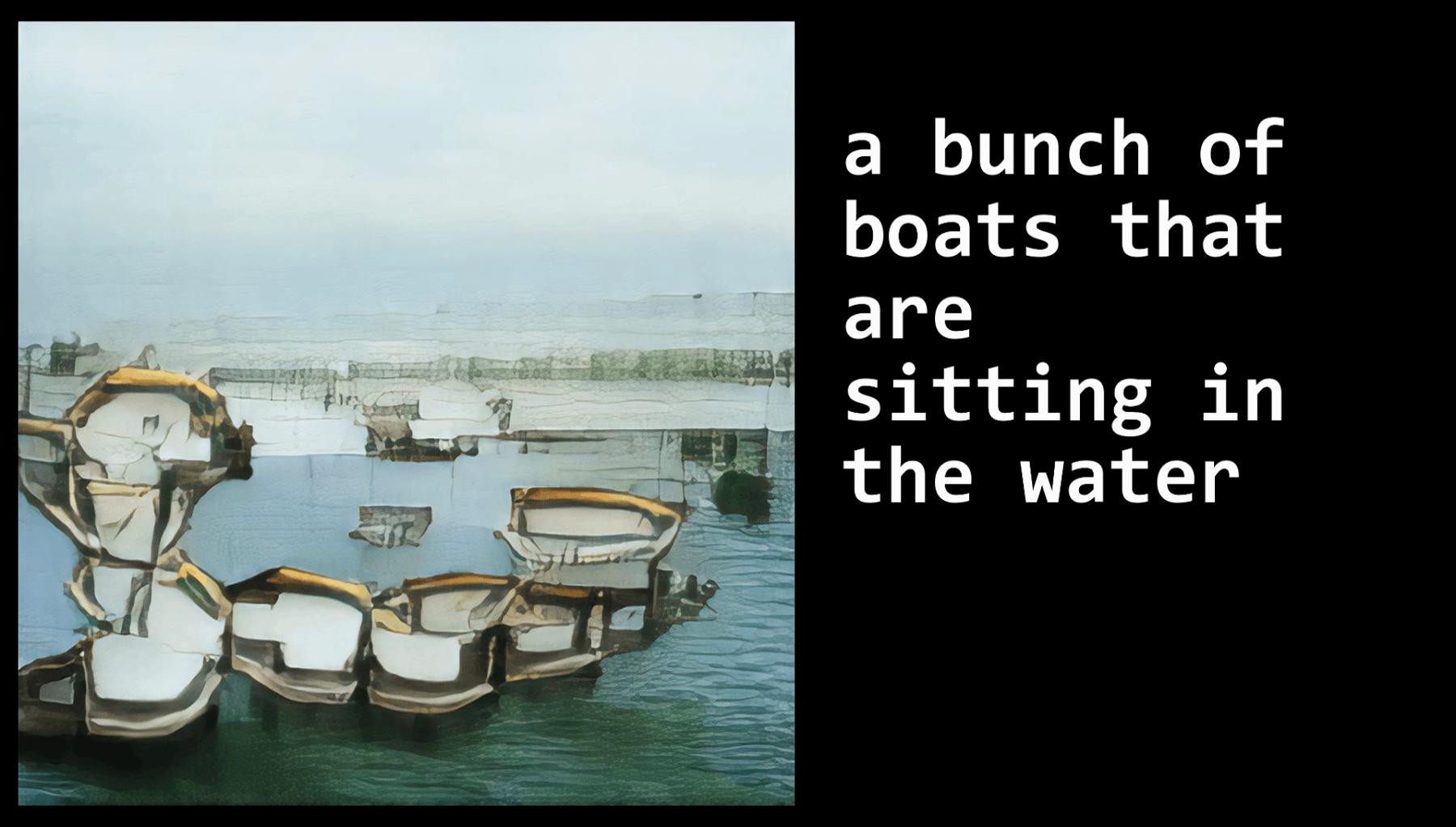

KK: Following the proliferation of digital technologies, any image that is created—photographic or algorithmic—is no more an image in the traditional sense of visual image but remains as specially formatted numbers. When a machine has to read these images, for instance, to detect the characters from a vehicle license plate or apply a filter to the image being edited, the machine reads and manipulates these coded numbers. Only when the image has to be presented to the human eye, these formatted numbers are re-coded as digital light with corresponding RGB values, attaining a momentary status of becoming a visual image. This applies indistinctively to any form of image, and the distinction of photorealism or computer-generated imagery (CGI) remains only for the human eyes. Hence, the status of visual image has already undergone a major alteration. Using this premise, my practice involves making algorithmic images where the process of creating these visuals are differently related—which is neither photographic nor a hand-drawn sketch. The entire image is coded as procedural driven generative visuals that may or may not have a reference to the outside world in any case, thereby avoiding direct representation but can be the visualisation of a sound, or a movement, or a force, etc. In this era of algorithmic computation, data visualisation is the visual paradigm and not a representation of the real world. The Talking Heads video is a conversation between two neural-network artificial intelligence (AI) models. The Im2Txt model describes the images in words, and the AttnGAN model interprets the text into visuals. These neural network models take this entire argument a step further after being trained on tonnes of real-world images, as they try to simulate real-looking images. The entire post-truth deep-fake images phenomenon operates from this paradigm and is now actively shuffling the discourse on the truth claims of photographic realism.

Stills from Talking Heads, Video, 2019.

AB: You have talked about biometrics as a kind of “datafication” of bodies, and the states’ efforts to quantify its populace through national programs like the UID. There seems to be a similarity in these efforts and say, the drive of colonial anthropological photography which, at one level, seeks to define and delimit the colonial subject. How do you see the similarities or differences between this and the current technologically driven efforts to collect biometric data across the world?

KK: I see the Aadhaar project from the Indian government as the beta testing project for biometric-based identification to be implemented in the future, across the world. All the popular science fictions portray a future where bodily traits increasingly become synonymous with access/control or identity, and yet the use of biometrics (specifically the fingerprints) has so far been for very limited purposes, and it works only at the institutional level, for instance, criminal records. After several unsuccessful attempts and controversies in other first world countries, the Aadhaar got implemented for all the residents of India. What a successful biometric system imagines to achieve is to break these institutional boundaries, such that multiple parties can make use of the biometric or the fingerprint data for various purposes, without limitations. But the viability of this needs to be tested, and India is a good testing ground because of its a) population of 1.2 billion, and b) the diversity of people offers a rich sample. We have seen this happen during the colonial era, before the establishment of the fingerprints technique, there was an identification system based on anthropometry—the physical measurement of the size and proportions of the human body, introduced by Alphonse Bertillon, a French policeman, to measure and identify criminal bodies. This system was introduced in Colonial India as an anthropological tool to investigate the basis of caste and race. Thus, a massive amount of bodily measurements were collected from the natives for little, or no money. Around the same time, William Herschel, a British administrator in Bengal, used the palm print as the signature for the first time, while making an agreement with Rajyadhar Konai—a local contractor. Herschel continued his practice of using fingerprints for administrative purposes, implementing it for criminal identification as well. He collected a large number of fingerprints, which later Francis Galton extensively studied to write the seminal book Fingerprints (1892), thus gaining scientific reliability for fingerprints as a unique identifier. Therefore, consciously or not, Aadhaar can be seen following these footsteps when it comes to collecting bodily data to study the viability of identification and control.

In the second part of this interview, we delve into the ways KG’s practice takes on digital activism and awareness building, as well as continuing the discussion on his extensive research regarding the implications of national digital data collection schemes like Aadhar.

All images courtesy of the artist.