Travels with Women: On Courtney Stephens’ Terra Femme

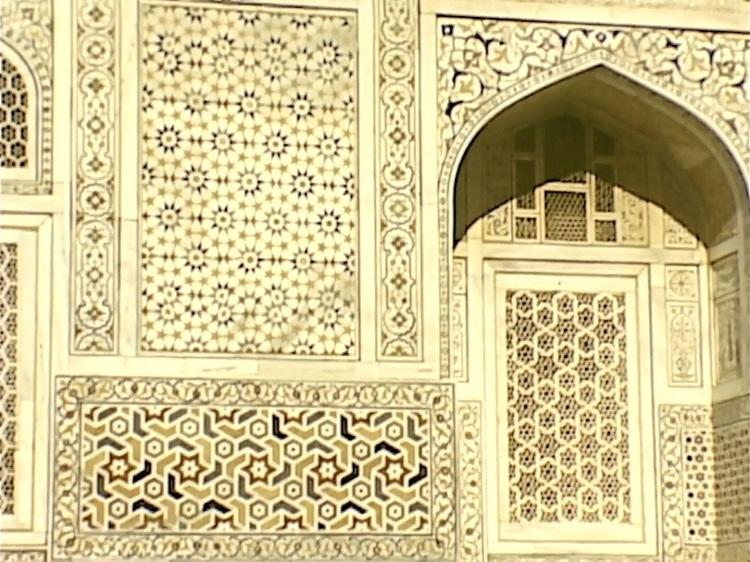

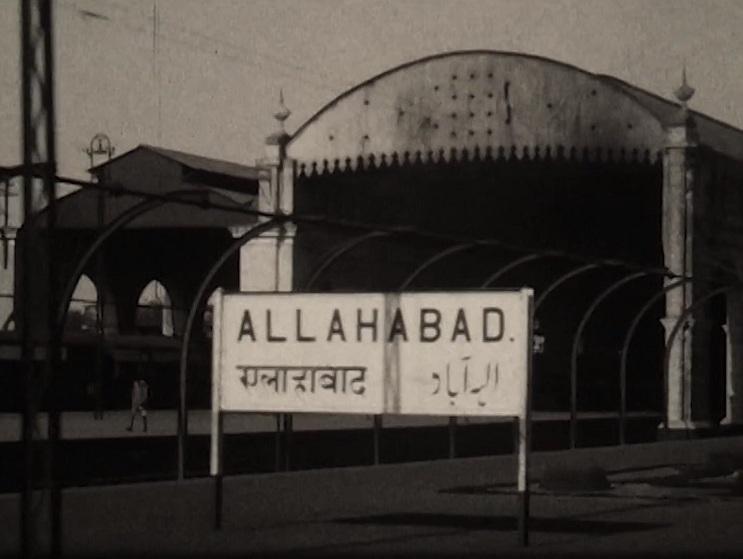

Courtney Stephens’ essay film Terra Femme (2017-21) uses archival and found footage shot almost entirely by amateur female filmmakers between the 1920s and 1950s. It strings together a poetic argument about the possibilities of travel narratives as a form of minor institutional filmmaking. Through narrative assemblages, Stephens attempts to recover such film practices from the more industrial versions of the imperial exotic that ruled Western cinemas until the middle of the twentieth century. The filmmaker travelled to India after being diagnosed with a partial paralysis that created “blank spaces” in her head—echoing Joseph Conrad’s ethic of male adventurism. Seeking to excavate the legacies of travel filmmakers like Ursula Graham Bower and others who framed popular locations like the ghats of Varanasi or the Taj Mahal in personal ways, she ultimately "failed" to imitate their gazes with her own camera.

The films and footage Stephens recovered from archives are largely shot by white women, riding the crest of technological and social advances being made in the early interwar years. This phase had encouraged solo or family travels across exotic locales in the Middle East, South Asia and China as well as Central American countries like Guatemala. The few exceptions include black women filming home movies in the American South, providing a view of how everyday cultures of black America began to spread after the Jim Crow era.

Some of the filmmakers included within Terra Femme can loosely be described as "adventurers" too, such as Bower and Adelaide Pearson. While Bower filmed and wrote early accounts of the changing martial traditions of the Nagas during the looming threat of a Japanese invasion through North-eastern India in the early 1940s; Pearson may have shot some of the earliest moving footage of Gandhi in colour. As can be guessed easily, these films are now admissible into the larger canon of anthropological narratives that were being made since the earliest days of filmmaking. They add to this archive a dimension of informality and spontaneity, while still remaining implicated within the larger ideas of colonial travel (of course, literary narratives of women’s travels in colonial India go back much further in time). Bower’s work, for instance, was still framed within the larger objective of securing the British-Indian frontiers for colonial rule. Other women filmmakers in India, like Nancy Kendall, were typically wives of British civil servants. Their work directs our attention towards almost comic performances of excessive male rituals that were a stand-in for the British display of power in colonial India.

“Do modes of objectification and exoticism differ in women’s films than in those of Western men?” the director asks in her recorded voice-over, as she confronts the difficult legacy of women attempting to find freedoms within the shadows of domination. The film has also been shown with live voice-overs, marking a performative, shape-shifting aspect in the film’s exhibition history.

Stephens seeks to excavate a tradition of filmmaking that can buttress the handy, counter-intuitive myth of the "female gaze" in cinema. She remains aware of the limitations that can frame the production of such an alternative gaze and the privileges that can sanction it. Instead, she focuses on the wealth of details that can circulate around the notion of this myth even as one uses it as a loose, imperfectly defined structuring principle. The director is wary of insisting on transcendental differences between the ideas of female gazing and their male counterparts, which would imply absolute differences in ways of being. Nonetheless, she is interested in pursuing the significance of such "self-propelled" journeys undertaken by women in an effort to see the world differently. What are some of the properties of this mode of looking? Talking about the films of Carry Wagner, who belonged to a Jewish immigrant family in New York and ran an antiques jewellery store which often sent her looking for such items abroad, she says, “Wagner points her camera at in-between spaces and personal decoration. You could even describe her style as anti-monumental.” Elsewhere, describing the scenes of another filmmaker, she remarks on her ability to shoot “…minor spaces, where life goes on unrecorded, outside the flow of historic time.”

The details of life, work and ordinary ways of inhabiting exotic locales accumulate in these narratives. This sometimes lead to a critical mass of "over-photographed" natural locations and spaces, which drew complaints from men about how these travellers wasted film footage on faceless mountains and forests. As these commonly filmed scenes reveal, however, women often lingered with their films—transforming the mechanics of a consuming gaze into something more like a desultory stare (or “excessive looking” as Stephens suggests). Their work often allowed such locations—and the people they contained—to stare back at the filmmaker in various states of conscious and unconscious resistance, ranging from boredom to impassivity. It is in the nature of these films, ultimately, as Stephens suggests, to provide the means to look for gentler modes of gazing and wonder if that could shape, and perhaps even "produce", the world differently onscreen.

To read more about the films screening at the 2022 edition of the Dharamshala International Film Festival, please click here, here and here.

All images from Terra Femme by Courtney Stephens (2017-21). Images courtesy of the director and the Dharamshala International Film Festival, 2022.