Representing Lived Histories: In Conversation with Supriya Dongre

The Serendipity Arts Residency is an intensive studio-based residency for emerging artists in India, providing a space and resources to develop their practice, work on a new project and interact with the broader arts community in New Delhi. Supriya Dongre, currently pursuing a Masters in Photography Design from the National Institute of Design, Ahmedabad, was one of the four artists-in-residence for the current year.

Over the last three years, her work has touched upon themes of suffering, trauma and reconciliation. Anchoring herself in human conditioning and personal records through anecdotal research, Dongre conducted a visual study, focusing on semiotics and semantics as fundamental tools in understanding image narration. Her research is presented as an untitled installation at the Serendipity Arts Festival 2022.

In the first of this two-part conversation, Dongre discusses making the switch from being a chemical engineer to a visual arts practitioner, and also how caste plays into every sphere of life in India.

Installation view of Supriya Dongre's installation at the Serendipity Arts Festival at the Old GMC Building, Panjim, Goa. 2022.

PD: You have previously studied and worked as a chemical engineer before joining the National Institute of Design (NID) in Ahmedabad. Could you talk about how studying photography in an art institution has affected your visual art practice?

SD: Growing up in a Dalit family, every day is a representation of resilience. In a space like NID, I was able to introspect about where I come from, because I was introduced to critical analysis and the phenomena of body politics.

I feel that every transaction in life—from getting a private English education to practicing art—is tinged by connotations of caste. One such major transaction was getting into one of the top-most institutes for engineering, because that felt like an accelerator of shame for carrying a lower caste identity. The system is structured such that a tool for social reformation becomes a matter of privilege and a large segment of the minority communities still struggle with accessibility.

Discrimination and gaze are the norm in competitive institutes of national importance. This unresolved tension between academia, perpetuating the importance of education to mobilise socially and the position of a Dalit individual therein was something I wanted to reconcile with, and perhaps find a comfortable space for myself. Engineering became a major point for me to turn to design and art. It was the inception of wanting to find validation in lived experiences and work with exploring systemic realities.

NID also introduced me to trans-disciplinary approaches using multiple mediums of communication, to form a cohesive format of storytelling. For instance, when I used touch and materiality in my second installation, I was intrigued by how the politics of my identity helps enforce touch as a medium of connections and narrative building.

Still from Informational Redundancy. Video Loop. 3 minutes 50 seconds.

Still from Depersonalized. Video Loop. 3 minutes 4 seconds.

PD: What was your initial idea for the Serendipity Arts Residency? Can you also elaborate on the kind of research you have been conducting for the work you have put up?

SD: Being a second-generation educated Dalit woman, I grew up seeing my parents invest in socio-political activities, raising awareness and educational liberation for the community. Although most of my knowledge has been second hand, I came to the realisation that it is important to speak about ideas of resilience, identity, aspirations and their intergenerational transfer.

When I applied for the residency, I hoped to bring forth personal narratives of Dalit families and youth, anchoring myself to the strength of the community against the disguised form of discrimination prevalent today. My initial research was entirely observational, reflecting on the stories and anecdotes from my family. I took notes from my parents and grandparents about their understanding of caste and the Dalit identity. During this phase, I realised the traces of pain and conflict they carried, as well as the dignified and autonomous ways of living that my family strived hard to gather.

The following phase was initiated during the residency, where I started conversing with first, second and third generation Dalit youth. My interviews dealt with questions about how and when their caste identity was made evident to them, and how that felt. I was able to get a closer look into the various affiliations that people have with caste. Some felt that being Dalit was a lived reality and others seemed to be struggling with the personal versus the outside world.

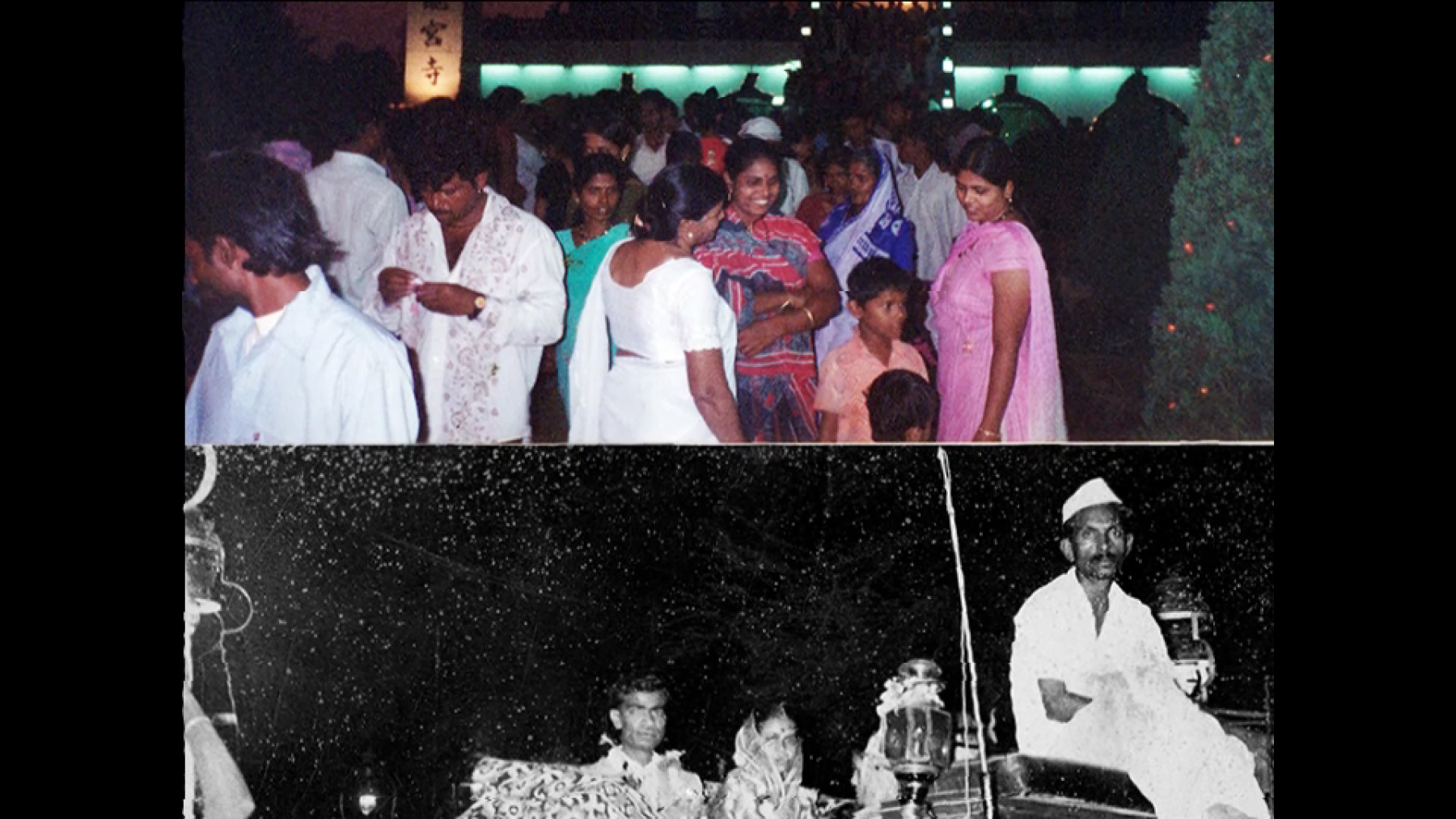

Installation view of 'Family Archive' at the installation at the Serendipity Arts Festival at the Old GMC Building, Panjim, Goa. 2022.

Still from Family Archive. Video Loop. 5 minutes 7 seconds.

For instance, a friend told me that college was the first time he realised the politics behind the words Dalit and Scheduled Caste; it made him feel small, and he constantly felt the pressure of proving his worth. He started getting comfortable after a close friend confided to being a follower of Ambedkarite philosophy, pushing him to learn more about where he came from and the power of a colloquial Jai Bhim amongst friends—an assertion of dignity. A conversation with another person led me to work with family archives because she was tired of the aestheticisation of pain and struggle and wanted to seek confidence and strength in personal and community histories.

With these narratives, I found commonalities in experiences, like there was a definite fear of being looked at differently or misjudged for our capabilities. This became my cue to work towards the notionality in caste borne out of human conditioning and perceptions.

To read more about projects from the Serendipity Arts Festival 2022, click here, here and here.

All images courtesy of the artist.