Troubling Empire: Bakirathi Mani on Seher Shah

Trained in architecture and fine arts, Seher Shah is concerned with the legacies of built structures and the genealogies of power embedded in constructed matter. Her practice explores the complex relations between architecture and its representation through mediums such as photography, drawing, printmaking and interventions with archival documents and sites.

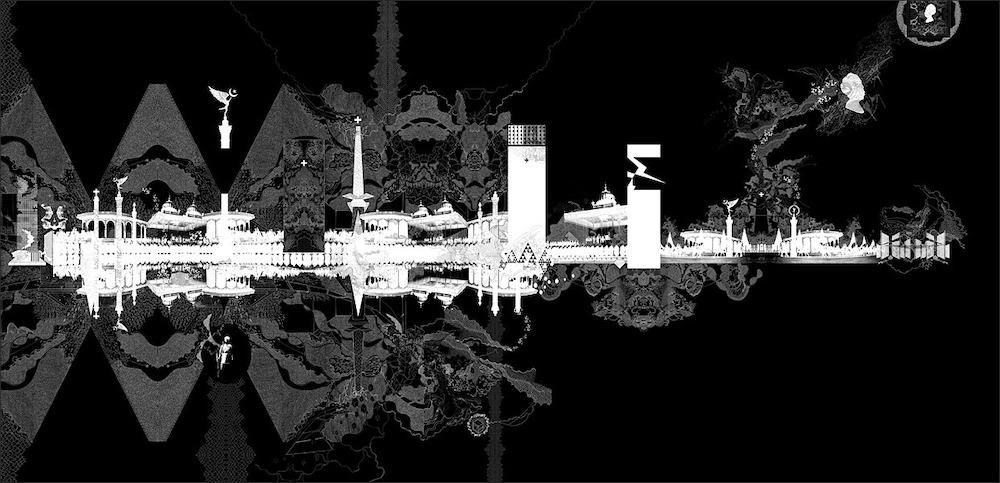

Geometric Landscapes and the Spectacle of Force. (Seher Shah. 2009. Archival Giclée Print. 58 × 120 inches. Image courtesy of the artist and Nature Morte Gallery.)

In the essay “Archives of Empire: Seher Shah’s Geometric Landscapes and the Spectacle of Force,” first published in Social Text and subsequently updated in the volume Unseeing Empire, scholar Bakirathi Mani unravels the challenges to “nationalist frameworks of viewing” present in Shah’s work. Mani focuses on a single work, “Geometric Landscapes and the Spectacle of Force” which contends with the visual traces of the Delhi Durbar of 1903, the American neo-imperialism of the late twentieth-century and the politics of the archival image. Mani uses the conceptual arch of the term “iconomy” developed by Okwui Enwezor. In an essay titled Archive Fever: Photography between History and the Monument Enwezor uses the term in the context of the 9/11 attacks to describe how the circulation, repetition and consumption of select images in the media supplants the event, creating an “iconomy” that exceeds the purpose of documentation to become “…a vast economy of the iconic linking archive to traumatic public memory.” The power of the “iconomy” to distill the iconography of hundreds of images into the enframing of the moment of collision in the 9/11 attacks is reinstated even when the conditions of image-making are reversed. Chinar Shah’s project Bin Laden Situation Room depicts how the absence of documentary access to the execution of Osama Bin Laden creates an invisible or absent archive.

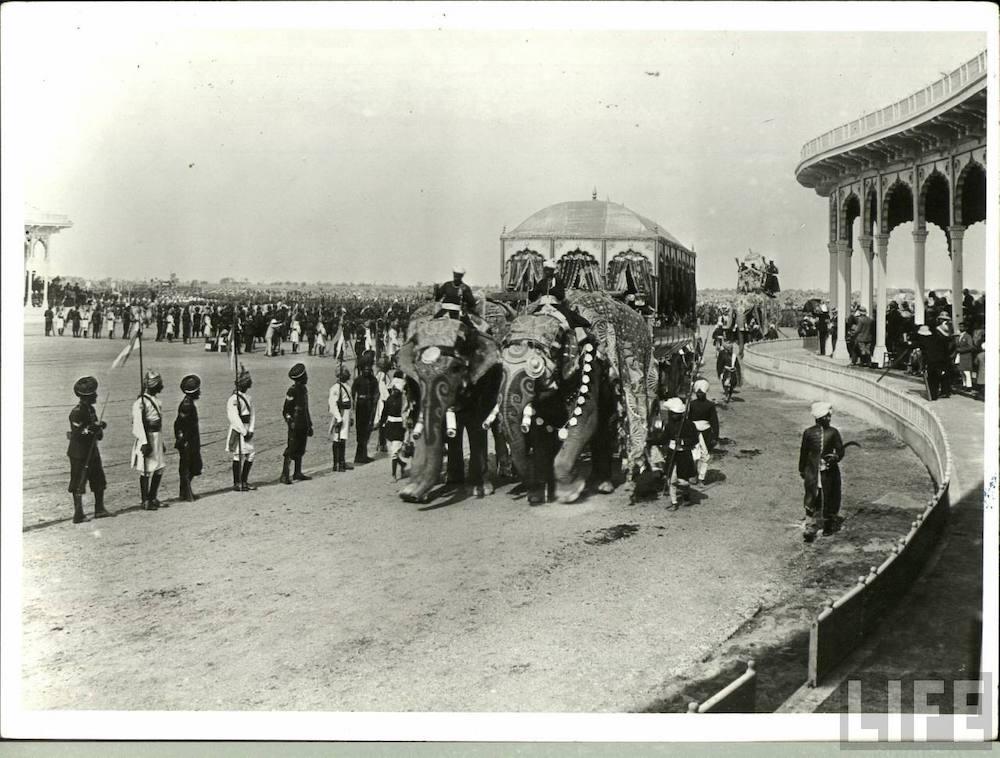

Photograph of the Delhi Durbar of 1903. (In Life Magazine, Sourced via Wikimedia Commons.)

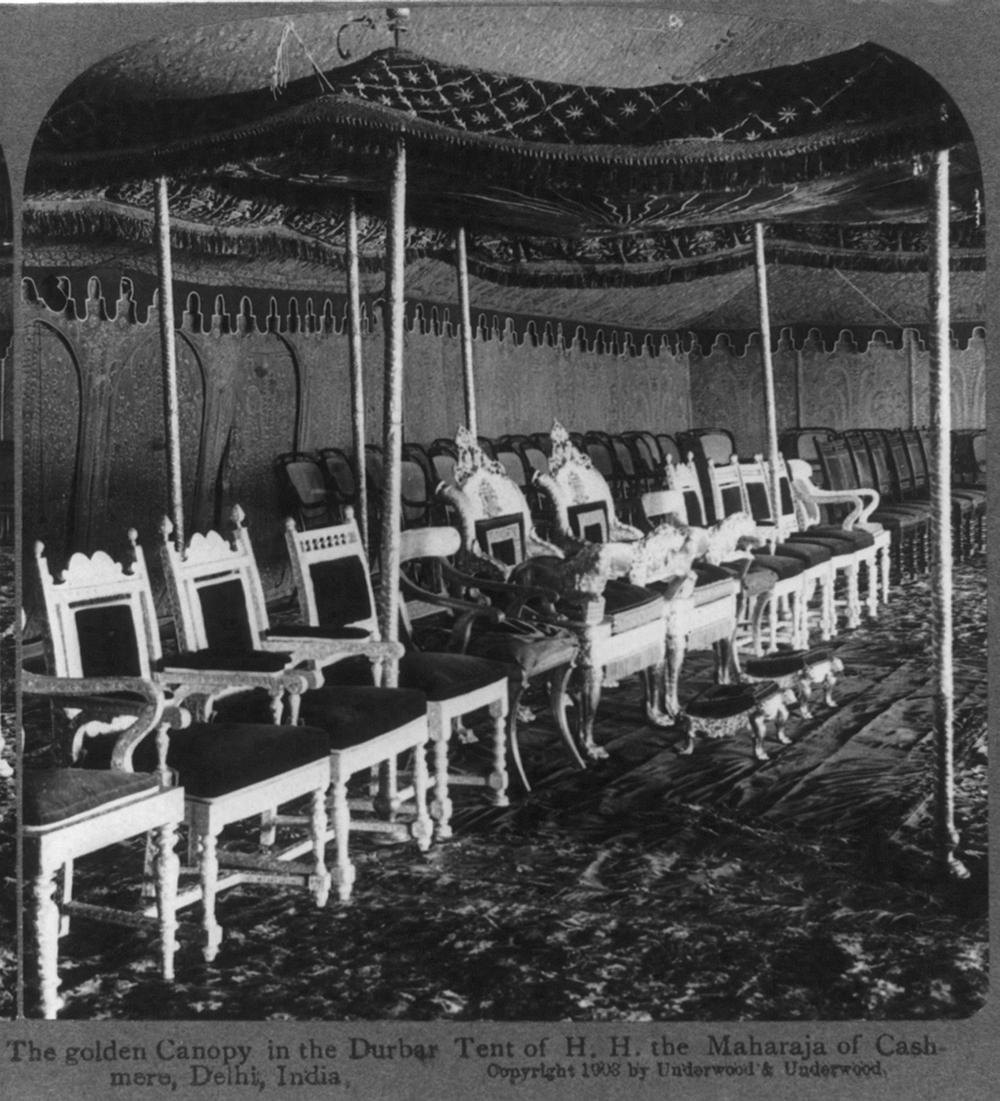

Stereograph of “The golden Canopy in the Durbar Tent of H.H. the Maharaja of Cashmere, Delhi, India.” (Created by Underwood & Underwood. [c. 1903]. From Library of Congress Prints and Drawings Online Catalog.)

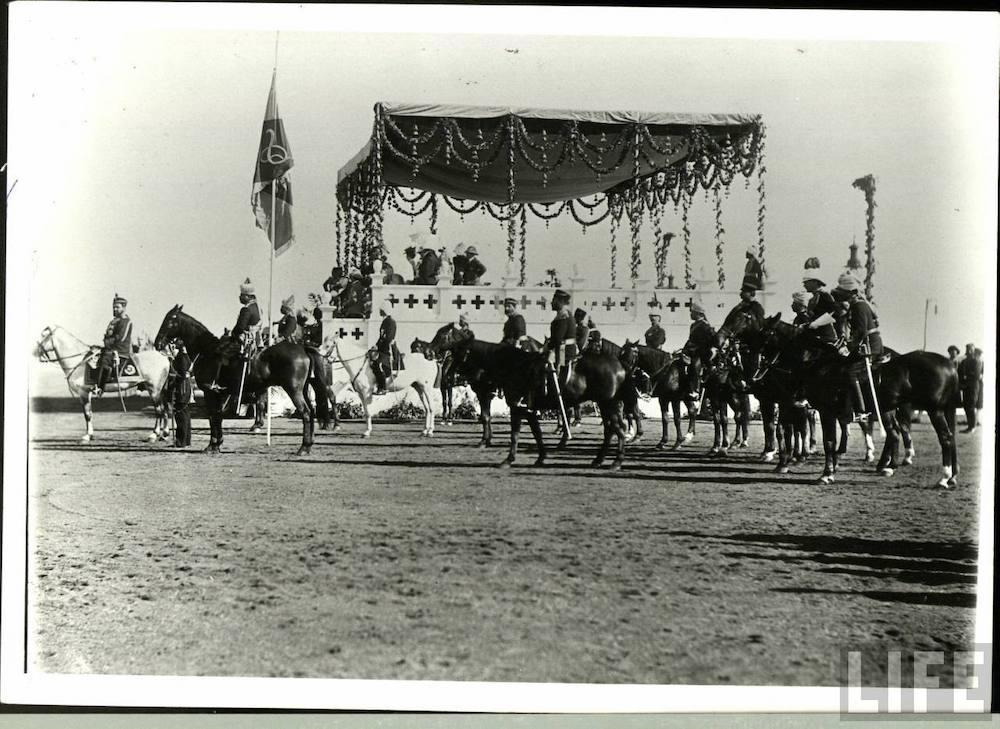

Among a series of rituals conducted since 1877 to instate British monarchy as the legitimate source of rule in the colony and to mark new succession to the throne, the persisting image of the Delhi Durbar of 1903 is one of unparalleled extravagance. The spoils of empire scaffolded by pavilions and tents created a temporary yet declarative space for the performance of empire which Bernard Cohn notes in “Representing Authority in Victorian India” was an effort to “... construct a ritual idiom through and by which British authority was to be represented to Indians.” In Shah’s double negative print, the promenade, amphitheatre, select attendees and objects are reproduced in ornate detail, mimicking the style of the Durbar that Cohn terms as “Victorian Feudal.” Seamlessly woven in are motifs of skyscrapers, cenotaphs and obelisks—gesturing towards a different landscape of memorialisation. Mani focuses on the location of the 1903 Durbar pavilion structure with the revealing symbol of a coffin draped in the American flag, to highlight the transhistorical linkages between two empires, as indicative of Shah’s interest in probing the persistence and transformation of extractive, settler and colonial modes of power and their symbolic reflection in the built environment.

Photograph of the Delhi Durbar of 1903. (In Life Magazine, Sourced via Wikimedia Commons.)

Photograph of the Delhi Durbar of 1903. (In Life Magazine, Sourced via Wikimedia Commons.)

“Geometric Landscapes and the Spectacle of Force” was first shown in a solo exhibition at Nature Morte in New Delhi titled From Paper to Monument. The exhibition title is evocative of the movement that Foucault gestures to in stating that “…in our time, history is that which transforms documents into monuments.” In Archive Fever, Enwezor argues that Foucault is establishing the relationship between temporality and photography, that monumentalisation is a process of succession that erases the fragility and temporal limit of the document, akin to the mediatised perception of events in an “iconomy.” Mani cites Shah’s concerns with the techniques of monumentalisation inherent to archives, methods of preservation and replication that position the work as a challenge to the edifice of public memory and history as “monument.”