Screen Geographies: Split Screens in Perceptual Transfers

Still from River in the Eye (2022) by Hetal Chudasama.

Perceptual Transfers, curated by Najrin Islam, brought together moving image works by more than 20 women artists from the Faculty of Fine Arts, Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda. The overall curation gave viewers a broad sense of the themes and preoccupations that artists have engaged with through the medium of video while also providing an insight into individual perspectives and personalities. One aspect that stood out in the programme was the use of split screens across several films.

The use of the split screen as a formal device within the context of moving image practices is not new, as digital media has enabled greater ease in manipulating the moving image. It has been deployed in several films, art installations and in the presentation of news. In a post-pandemic world—where our everyday interactions are frequently mediated through the form of a grid on Zoom—it has become an almost ubiquitous form.

Still from I Saw a God Dance (2018) by Ayisha Abraham.

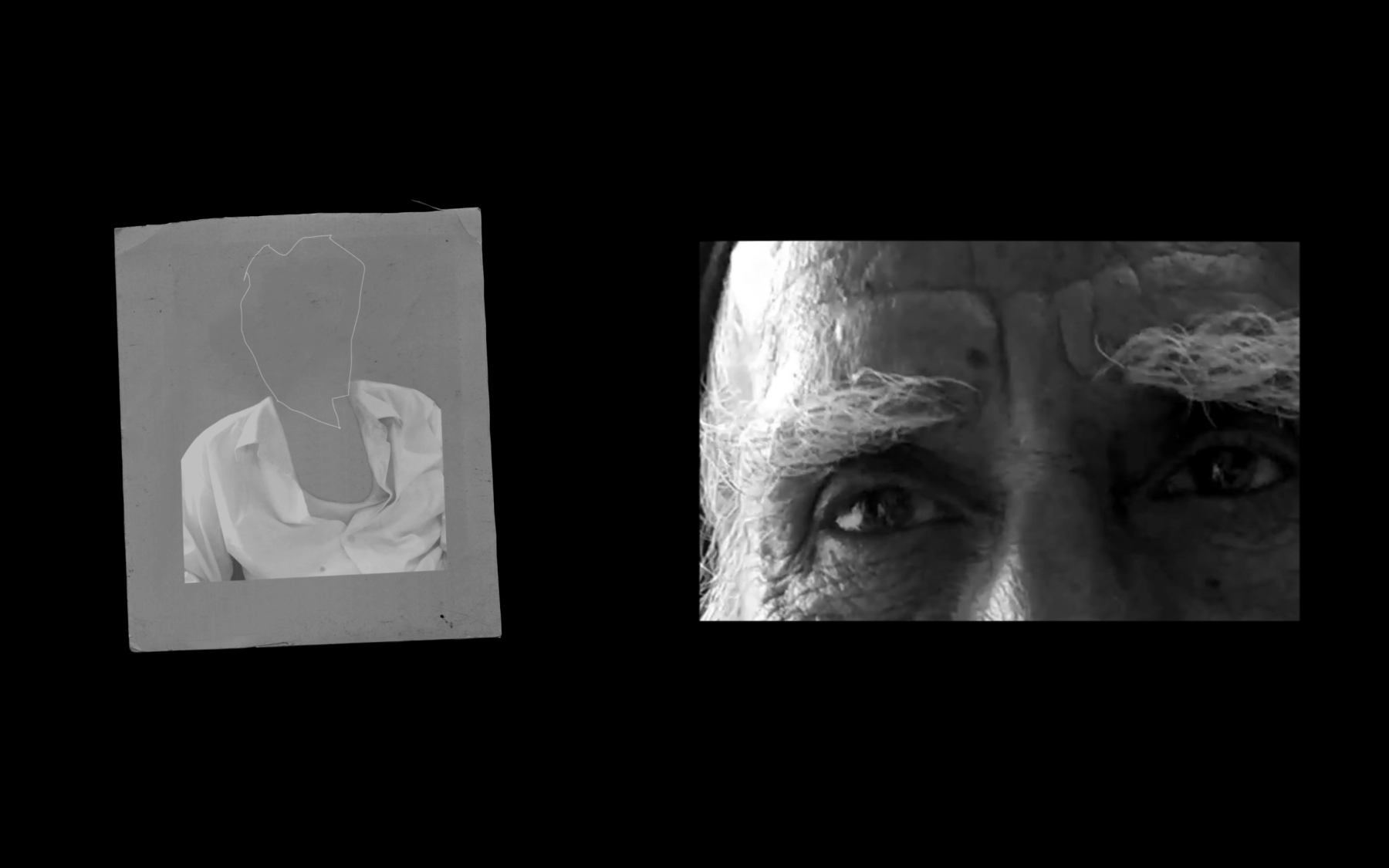

A thematic concern explored in one of the segments, mentioned by Islam in a conversation with the writer, was that of screen geography and the occupation of space. Formally, one can make several connections to this notion across the programme through works that make use of the split screen. Pahul Singh’s Ikk Kambdi Lakeer (A Quavering Line, 2022) deploys the split screen in several excerpts within the series. The use of the form evolves organically from the content as the artist explores a family history of the 1947 partition. The split screen also works at several other registers, indicating a disjunction between past and present, language and silence, personal and collective. The two sides of the screen speak to one another as they visualise the missing link—that of the voice of the testimonial witness. We watch an old man speak through extreme close-ups of his face, as a boundary line demarcating a state quivers in response to the intonations of the voice that remains unheard. Singh’s work plays with such fragments, allowing the viewer to piece together a larger picture, much like a jigsaw puzzle.

Still from A Quavering Line (2022) by Pahul Singh.

The experience of partition finds reference in Gargi Raina’s Black Box (2019). The film focuses on an interview with Homai Vyarawalla, shot in Vadodara in 2004. Here, she recalls photographing the decisions that led to the partition of India and Pakistan as well as her experience of its violent aftermath. The last set of photographs by Vyarawalla we see in the film are of a Ramlila procession and a Taziya procession, both taken in Old Delhi. As Vyarawalla talks about how no one really wanted the partition towards the end of the film, Raina deploys the split screen to display video footage of crowds gathered for Muharram and Dussehra in the present day. The use of moving image in a split screen, with its dynamic rhythms and scale, betrays the underlying tensions that are present, especially in a state like Gujarat with its own recent history of communal violence. The act of splitting here alludes to rupture and violence.

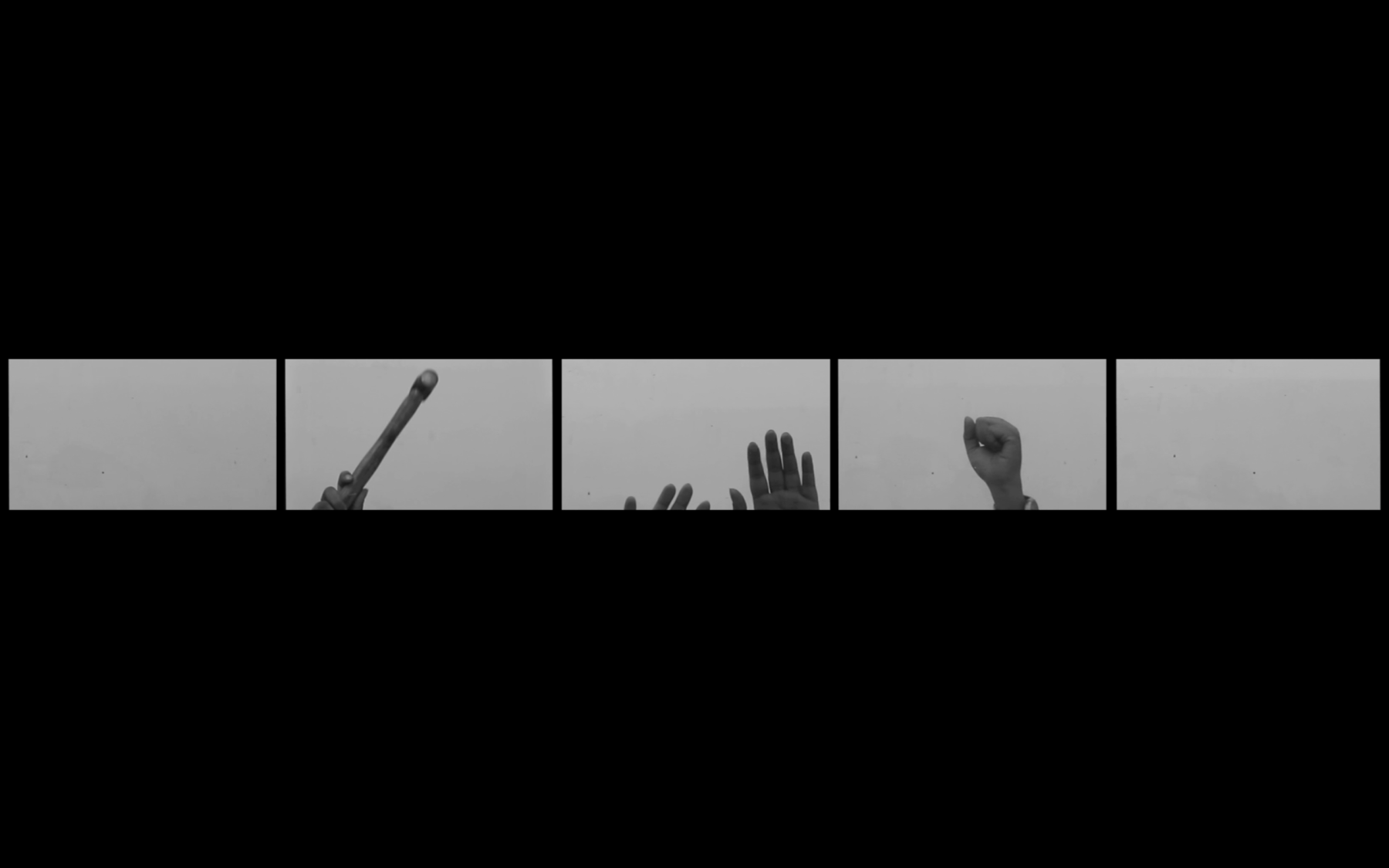

The notion of violence is implied in Kunathraju Mrudula’s Try… Try… Try... (2016). Dividing the screen by breaking it into five panels presented horizontally, the screens appear as windows or panes of glass upon which women’s hands beat, knock or draw attention to with increasing desperation. The compact nature of the shots creates a sense of suffocation and an inability to escape. While the work was made before the pandemic, one is reminded especially of the lockdown with reference to the increase in incidents of domestic violence as women were confined in their homes and often lacked access to other support systems. The nature of repetition within the work signals ways in which splitting the screen is not always a divisive one, as multiple instances of the same experience are collectively referenced.

Still from Try…Try…Try… (2016) by Kunatharaju Mrudula.

The existence of multiple screens forces viewers to interact more with the simultaneous narratives being presented. The act of deriving meaning from such forms is unifying, as a viewer may interpret the several fragments as a whole. This logic is apparent in Katyayini Gargi’s The Centre Does Not Hold (Patterns Emerge) (2020). The screen is presented as a line of four segments, which appear looped and in constant motion. The instability of the pandemic finds expression as we are offered a glimpse through four windows into different worlds. The title of the work leads one to search for patterns that connect the different segments, as one assumes a unity in narrative or a co-existence in time.

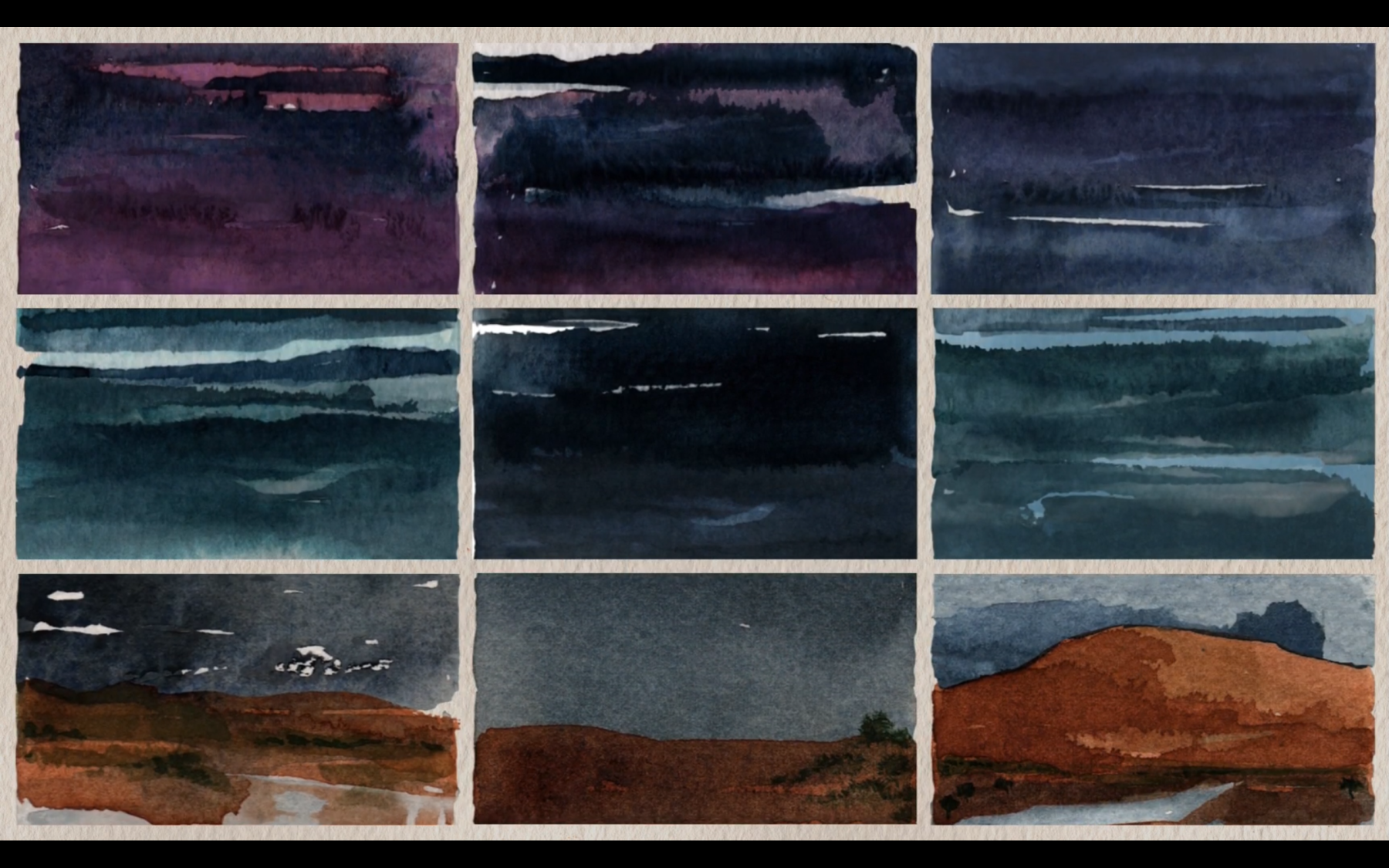

Another work made after the pandemic is Fleeting Moments (2022), in which Nina Sabnani animates watercolour paintings by Shrilekha Sikander. The work plays with the elasticity of time and space to evoke the transitory and transient nature of spaces. Based on memories of journeys made to and from Mumbai and Murud-Janjira in Raigad over a period of forty years, the work meditates on views of the sea and the coast in monochrome and colour. It opens with a 3x3 grid of images and then morphs into different configurations of the grid before finally returning to the 3x3 format again. The work collapses and compresses time and space as both duration and distance become relative and are open to interpretation.

.png)

Still from The Centre Does Not Hold (Patterns Emerge) (2020) by Katyayini Gargi.

In The Language of New Media (2001), Lev Manovich references the split screen as a technique of spatial montage, where the traditional sequential mode of linear time is replaced by the spatial and the simultaneous. Manovich writes: “Time becomes spatialised, distributed over the surface of the screen. In spatial montage, nothing need be forgotten, nothing is erased.” As our present becomes increasingly complex and differentiated, the singular screen can no longer contain our current reality. In this context, spatial montage becomes a resourceful device with the radical potential to expand film to better represent the fragmented nature of experience.

As our world becomes increasingly mediated through the screen, it begins to bifurcate, shifting in scale along the axes of space and time. This fluidity is also in play as the split screen represents both a sense of division or rupture as well as a sense of simultaneity, unity or connection. The pattern of using a split screen that emerges from the VASCA archives perhaps indicates a shift to the exploration of the surface of screen as more complex grid lines are needed to map experience. Art, as it anticipates the future, is perhaps imbibing a new visual culture where perceptual transfers occur on multiple registers and defy simple forms of classification, organisation and interpretation.

Still from Fleeting Moments (2022) by Nina Sabnani.

To read more about Perceptual Transfers, please click here.

To learn more about Video Art by South Asian Contemporary Artists (VASCA, formerly VAICA), please click here, here, here, here and here.

All images courtesy of Video Art by South Asian Contemporary Artists (VASCA, formerly VAICA).