Short Films, Long Tales: Pooja Gurung and Bibhusan Basnet at PhotoKTM5

As part of a curated film programme titled “Short Films, Long Tales” at PhotoKTM5 on 28 February 2023, the filmmakers Pooja Gurung and Bibhusan Basnet shared a few words about their practice. Having produced films for over a decade, Gurung and Basnet have amassed a cult-like following for their short films that deal with sensitive issues with the utmost care. Combined with their cinematography, which renders each frame a puzzle full of hidden meanings, their films have tugged at the hearts of audiences at prestigious film festivals such as the Venice Film Festival, the Sundance Film Festival, and the Toronto International Film Festival, among others. Before screening their films The Contagious Apparitions of Dambarey Dendrites (2013), Dadyaa: The Woodpeckers of Rotha (2016) and The Big-Headed Boy, Shamans and Samurais (2020), the filmmaker duo briefly introduced their work, with Gurung concluding, “The films we have produced are now yours. What you see means whatever you want it to mean.”

Their first film, The Contagious Apparitions of Dambarey Dendrites, shows the trippy, fast-paced and action-packed adventures of Dambarey, a person without a home. In Nepal, huffing Dendrite glue (a popular brand of adhesive) to get high is unfortunately a common practice among people without a home, especially children. The protagonist and his friends, in a daze of hallucinations induced by Dendrite, follow dollar notes through the slums and streets. The film ends with the protagonist standing beside a child, gazing at an animated fox that beckons them to follow it. This ending, in a way, sets the scene for the second film.

Dadyaa: The Woodpeckers of Rotha opens with a long shot of an old couple in the Jumla district of Nepal as they watch their son leave them without any notice. A sombre portrayal of a commonplace occurrence in rural Nepal, the short film is a masterclass in framing and effective mise-en-scène. The old man and woman are set in contrast throughout the film as they are spatially distanced within the same frame. As the couple quarrels about being left behind, they debate whether they should build a wooden effigy in the likeness of their son—a traditional practice prevalent in the region, to replace the villagers who have left.

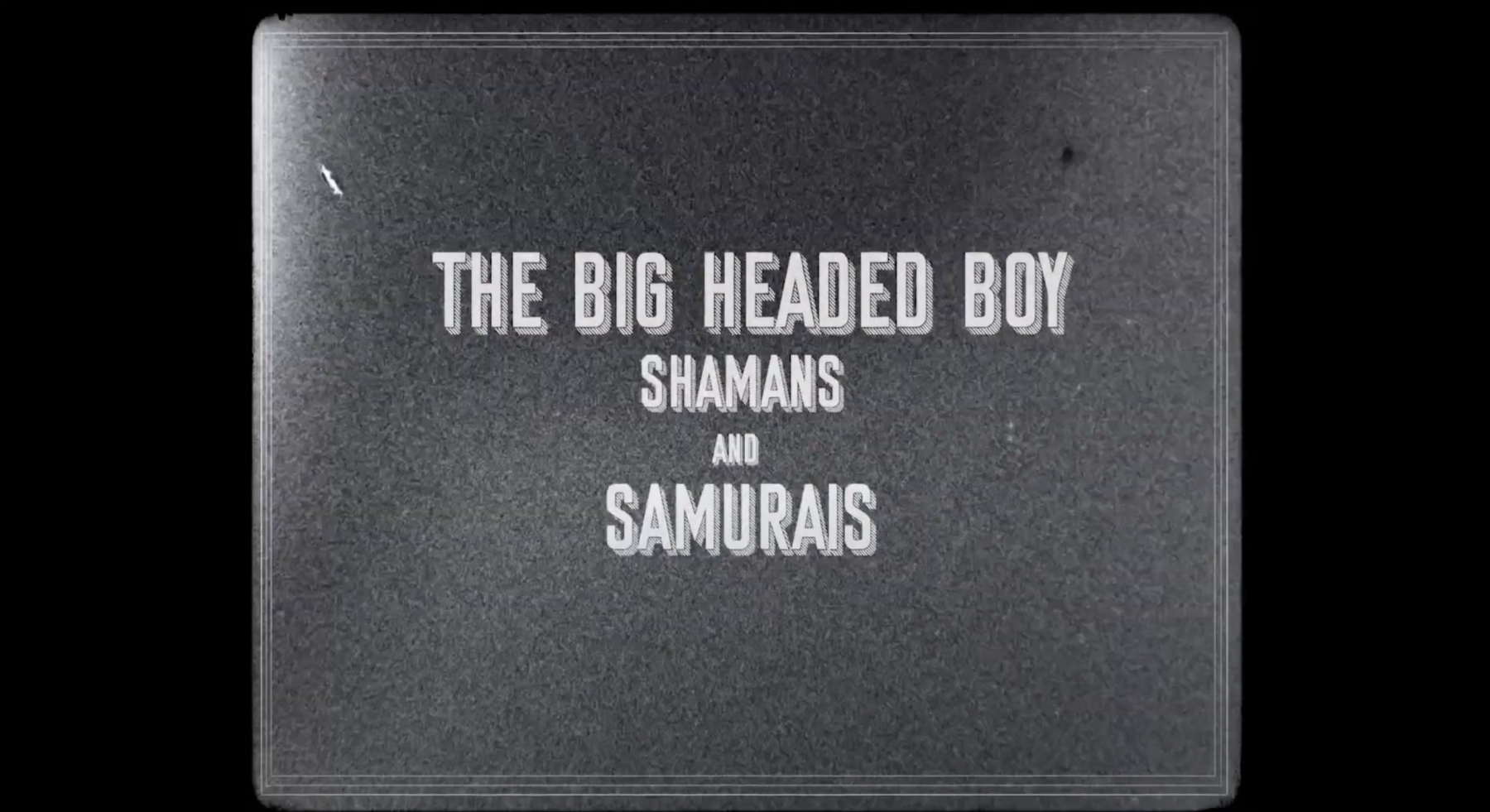

The final film of the day, The Big-Headed Boy, Shamans and Samurais, is arguably the duo’s most ambitious and experimental work. The film is shot almost entirely in black-and-white on 8 mm film. It is a deeply meditative narrative that revolves around a film crew’s journey into rural Nepal in search of the perfect child actor for their upcoming film. A tribute to Akira Kurosawa, the film adopts many of the auteur’s cinematographic quirks, such as jittering frames, the innovative use of motion and dynamic dialogues. While the film’s visual language is similar to an ethnographic film, it breaks away from a positivist approach to infuse the filmmakers’ perspectives of the events as they unfold. The narrative provides a commentary on the filmmakers’ experiences as they negotiate with their craft, even as non-diegetic sounds—like radio broadcasts—proclaim a violent and unstable political environment.

Apart from the storytelling prowess in the three films, a common thread that links them is the theme of longing. While Dambarey chases wealth and riches through hazy hallucinations, the old couple in Dadyaa longs to be reunited with their kin. The film crew that is searching for the last remaining key to their film also longs to find meaning in their craft throughout the film. In an interview with The Kathmandu Post in 2020, Gurung shared how important relatability and intimacy are for the duo: “We can’t even write the first sentence of the film if we can’t make it personal.” As their shared practice walks a fine line between the dichotomy of public and personal, the filmmakers use their films as vehicles to share deeply personal stories of grief, regret, violence, hopelessness and longing. Yet they also encourage their audiences to find their own meanings and interpretations. In doing so, they give enough autonomy to the audience to make the personal universal.

ASAP | art attended the opening weekend of the PhotoKTM5, where we spoke with the KTK-Belt Project and Monica Alcazar-Duarte about their works on display; Srizu Bajracharya wrote on the power of fostering community, as poignantly depicted in Fazal Rizvi and Aziz Sohail’s lecture-performance. Lastly, revisit Anisha Baid’s essay on the online iteration of The Skin of Chitwan, which is on display for the first time in its physical form this year at the festival.

All images courtesy of Pooja Gurung and Bibhusan Basnet.