An Event and Its Recalls: Evocations by The Fifth Wall

The Fifth Wall, a digital archive based on Navina Sundaram’s work and life, was recently mobilised by a series of multi-city screenings, thematic walkthroughs and discussions organised by the Sher-Gil Sundaram Arts Foundation and Goethe-Institut, India. In the session held at the Goethe-Institut, Bangalore, Merle Kröger (who developed the archive with Mareike Bernien) introduced the collection using the axis of media ethics and political potentials by presenting excerpts of films, letters, texts and commentaries.

The documents encapsulated Sundaram’s negotiations with the German mediascape in her forty years of work for the broadcasting channel NDR. Speaking from a migrant situated knowledge, she incorporated documentary and narrative forms into her work, rather than providing mere reportage. In a 2021 commentary on Sundaram’s film, So long as there are tears (1972), Lutz Mahlerwein, her colleague at NDR, recalled her steadfast commitment to not let the situation in India be presented in an ambiguous manner or from a Western perspective. The film encompassed Sundaram’s critical views on the twenty-fifth anniversary of Indian Independence. During the discussion that followed the introductory session, panellist Deepa Dhanraj mentioned how Sundaram’s operation outside of India’s media circle gave her access to important events like the Emergency and the Babri Masjid demolition, something that was far more difficult for Indian media back then.

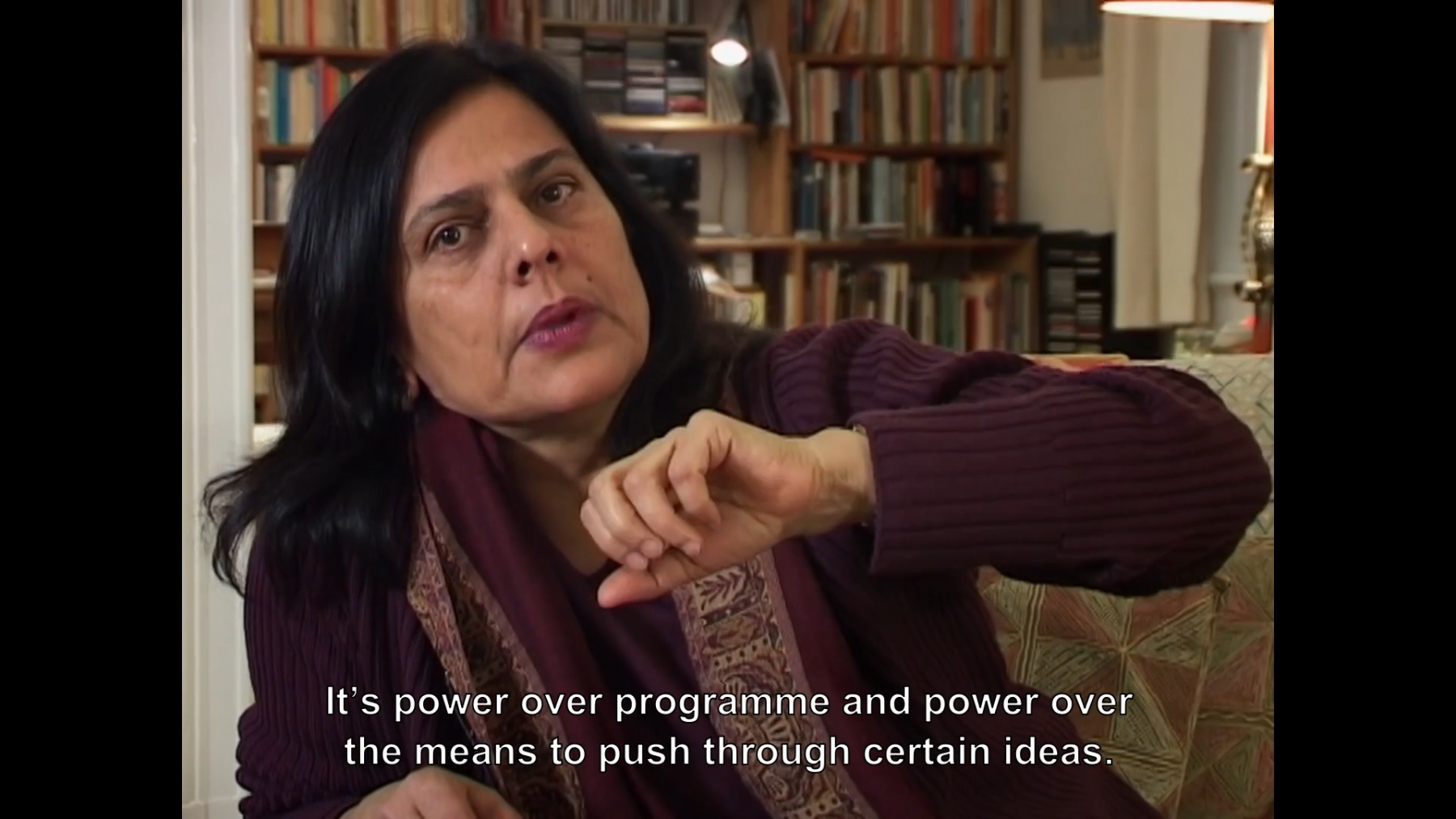

Sundaram reflects on her power as Editor at Weltspiegel (World Mirror). She mentions the envy she faced due to her status—as a multi-lingual Indian woman, who would rather work with contradictions than overlook them—which did not sit well with the Germans. (Screenshot from Power over programme [2004].)

In a letter to her parents from 1964, Sundaram described Germans as “nice and polite” while also recounting her first encounter with racial bias when looking for accommodation. The document asked for revisitation as it spoke to her report Binational Marriages (1982), which focused on the threats faced by immigrants and minorities, as well as German women who married foreigners and were deemed “impure.” In hindsight, what becomes apparent is the German media’s conservative attitude, Sundaram’s resistance towards being asked by her fellows to de-ideologise, and an awareness of the radical possibilities of media reportage as well as its shortcomings.

NDR afforded Sundaram an access that was quite rare at the time. It allowed her to cover not just decolonisation and its aftermath but also highlight the need of decolonising the self, evident in much of her work. (Screenshots from the report Binational Marriages [1982].)

Focusing on political potentials, Kröger deliberated upon the archive’s “nowness.” She revisited the Yugantar Film Collective’s archive through a conversation with one of its members, Deepa Dhanraj. Kröger contextualised Yugantar and The Fifth Wall within the framework of Archive außer sich, a project that was invested in seeing the archive as a site of co-production, speculations and the formation of alliances.

Kröger stressed on how The Fifth Wall goes beyond the biographical, becoming an important resource of access. This is crucial given how “public” television and media archives in Germany are barely accessible or affordable, with contributions by women correspondents often being forgotten. Many of the session’s attendees shared the sentiment that social spaces continue to exude machoism. The Fifth Wall also reminded some audience members of Susie Tharu’s Women Writing in India and CS Lakshmi’s archive SPARROW, where archiving itself became a feminist intervention.

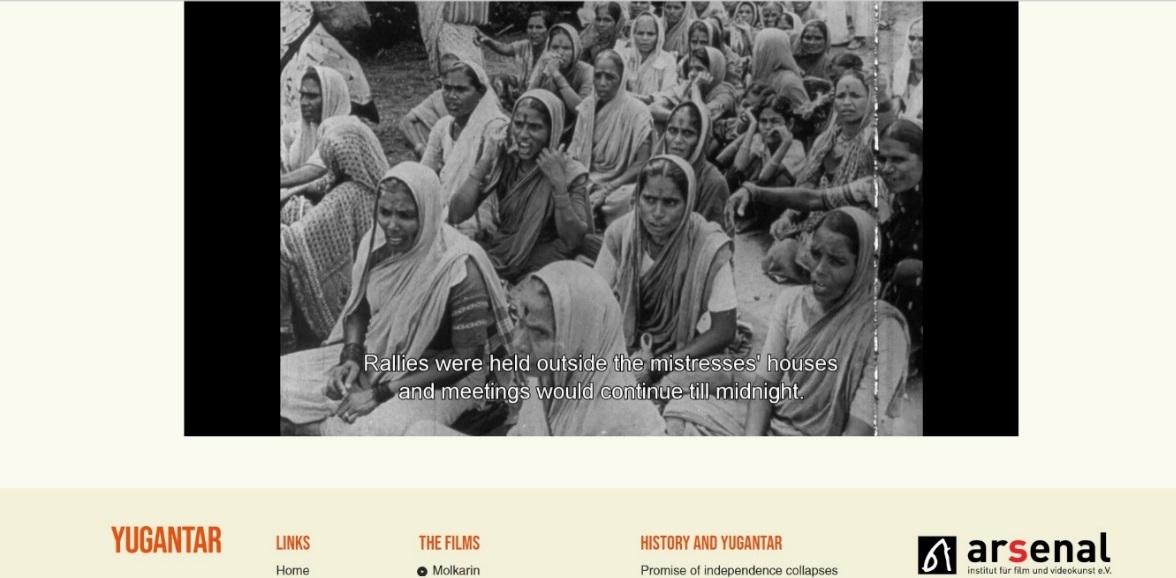

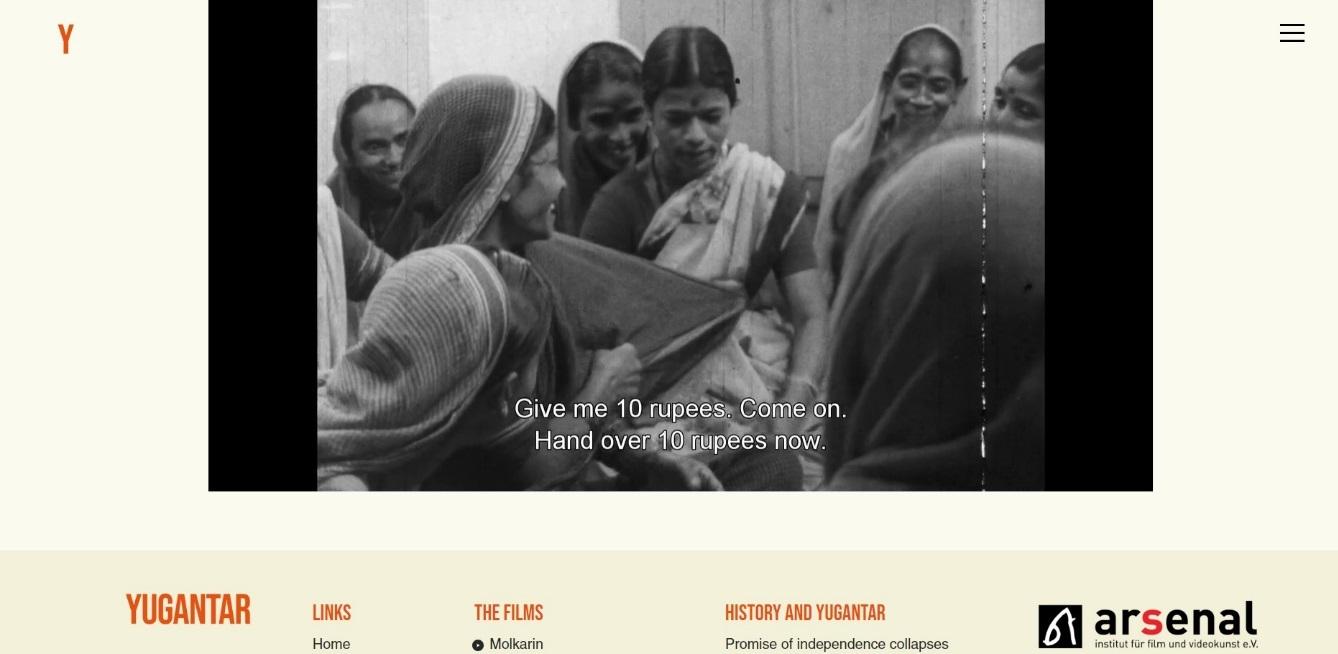

Founded in 1980, Yugantar made four films that were shown extensively between 1980 and 1985. Intent on creating a record of women's leadership within the workers’ struggle, they focused on the process through which solidarities are built. (Screenshot from Yugantar’s first film Molkarin [Maid Servant, 1981], from their website.)

For Yugantar, documentary filmmaking became a vehicle for political mobilisation, leading to a collaboration with women union workers. Historical re-enactments were an important part of their films, with women dictating how their working conditions should be portrayed on screen. Chapters on the Yugantar website detail their situatedness—revisiting the autonomous women’s movements of the 1970s in a post-emergency period. Upon the films’ long-drawn process of restoration with Nicole Wolf’s help, Dhanraj gained insights and noticed lapses in their process. This led her to probe their current relevance in terms of their distance from the actual context and its publics.

Dhanraj mentioned how initially, Yugantar’s films were intended for women’s groups in urban and rural informal sectors. The person behind the voiceover was often part of the group being addressed. While their restored films are being screened at film festivals, she is also working towards activated screenings in places where digital accessibility is limited, in an effort to rethink their audience as the films lead new lives. Dhanraj shared how communities have started to take charge of screenings in educational institutions, where women’s groups, sanitation workers, and union members constitute the panel. Instead of the traditional Q&A session, they discuss the film with the audience and respond to their questions, often reflecting on the needs and difficulties of political self-organisation today.

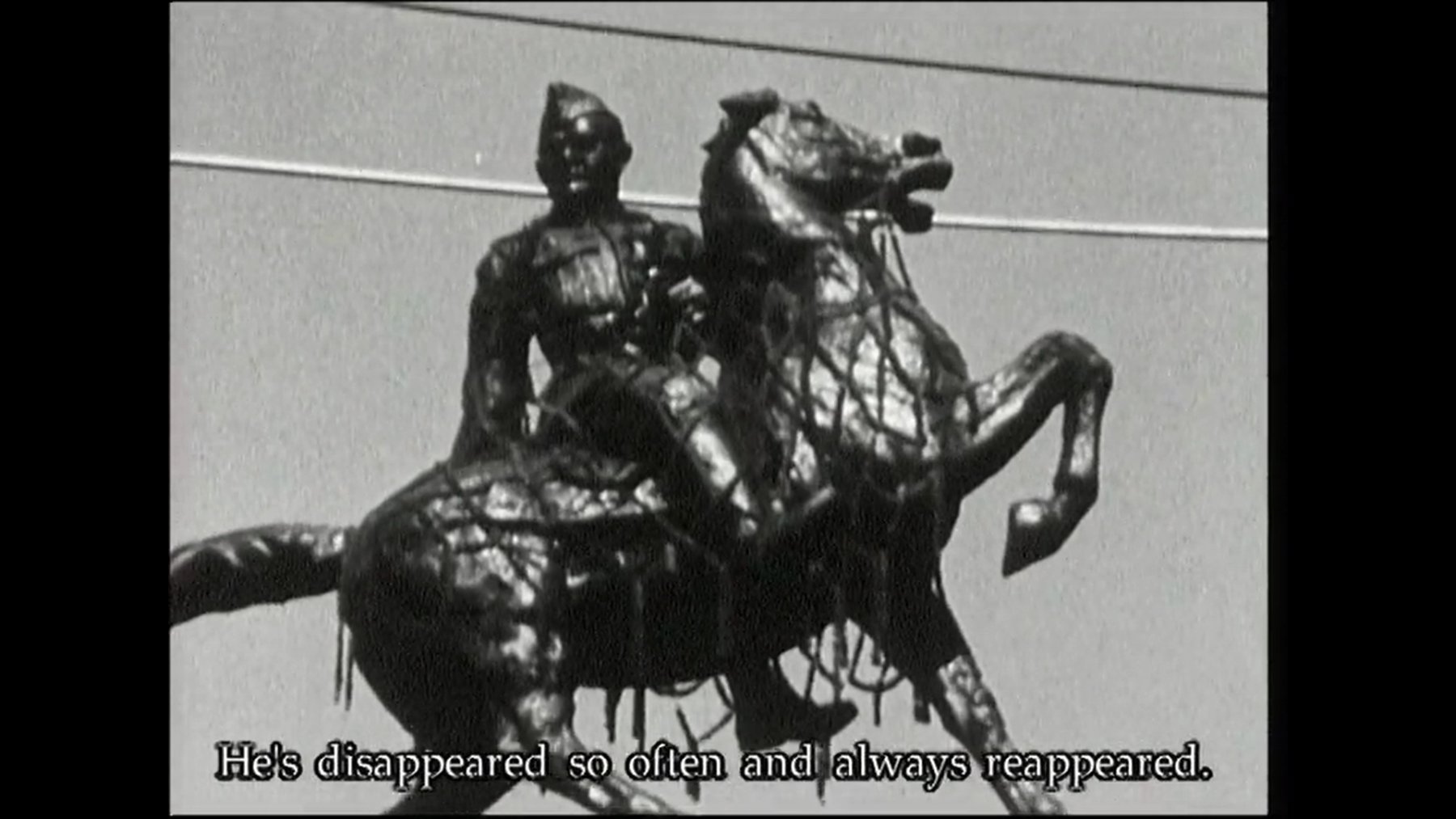

Building on demands placed by the present on an archive, Kröger introduced Portrait of a Patriot: The Saga of Subhas Chandra Bose 1941–1945 (1971). Sundaram’s film mobilised documents from various archives (in Britain as well as Europe) to trace Bose’s negotiations with political leaders while on asylum in Germany, when he formed the first Indian Legion. At the end of the film, Sundaram remarked on Bose’s legacy and how he has been periodically cited, eulogised and deified.

The translation of the original film from German to English—as part of building the archive—gave Sundaram an opportunity to finally lend her voice to the narration. She had been disallowed from doing so in the original on the grounds that her voice would not be taken "seriously enough." (Screenshot from Portrait of a Patriot: The Saga of Subhas Chandra Bose 1941–1945 [1971])

Following the screening, panellist Madhusree Dutta spoke on the current state of prisoners of war, identity confusion, and strands of nationalism when seen alongside fascism in the film. During the discussion, Dhanraj stressed on how Bose has been recast by the people in power today to fit their agenda, often by sidelining Gandhi’s stand on violence. Dutta added that Bose’s revival vis-à-vis registers of nationalism, intolerance, and militarism has to be reviewed. This gains significance given how a singular perspective of nationalism is being propagated today through ideological militarism, enacted upon and by ordinary people.

Screenshot from the film India - Hindus and Muslims (Sudaram, 1992).

Humour and role-play become potent political devices that enable women to share the alcoholic behaviour of their husbands and the subsequent harassment they face in all its intensity, otherwise too dark to relive. (Screenshot from Yugantar’s film Molkarin [Maid Servant, 1981], from their website.)

Towards the end of the programme, the room was heavy with an air of political disappointment from observing the broken social contract between people and the government and the escapist state of TV media today. The critical space of media has gradually given itself away to manipulation, with politically-partisan channels echoing the state, whose decisions are further influenced by private entities. Still, a few persevere in the face of frequent crackdowns and censorship by the state. The archives under consideration seek to be affective, rather than being definitive and prescriptive. They hold space for contradictions, sarcasm, humour, hope, and scepticism, as documents are retrieved for varying ends.

To read more about The Fifth Wall, read Madhubanti De’s piece on the radical vulnerability of the archive, Shivani Kasumra’s piece on the India launch of the archive and Ankan Kazi’s piece on the launch of a few films from the archive in 2022. Also revisit Ankan Kazi’s essay that locates the work of Yugantar in the context of collective documentary filmmaking practices in India.

All images courtesy of Merle Kröger, Mareike Bernien from The Fifth Wall and the Sher-Gil Sundaram Arts Foundation, unless mentioned otherwise.