Looking Beyond the Cinematic: Sabeena Gadihoke’s Selling Soap and Stardom

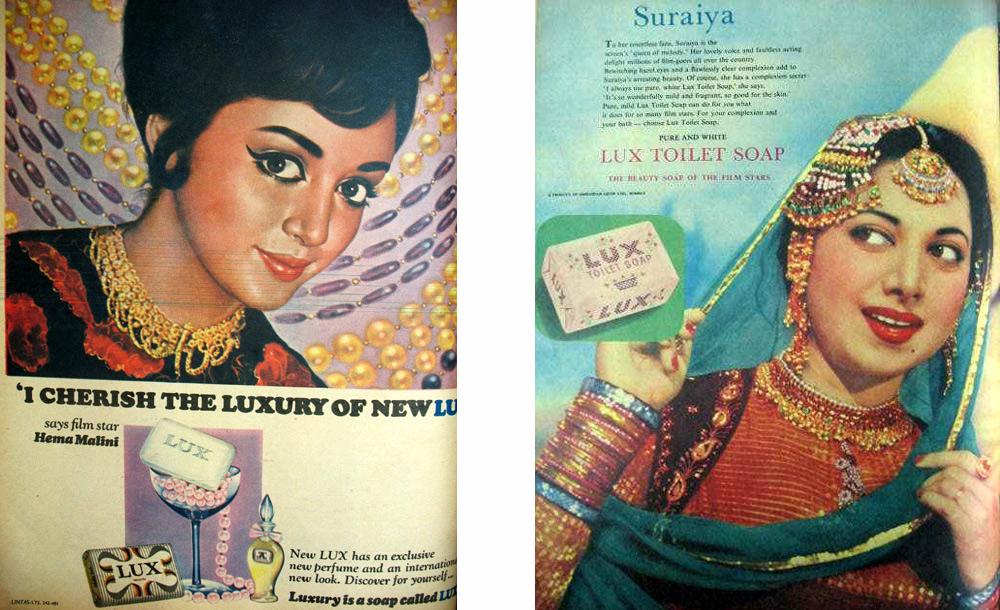

Left: ‘I Cherish the Luxury of New Lux' Says Film Star Hema Malini. (Print Advertisement for Lux Toilet Soap. 1969.)

Right: Suraiya. (Print Advertisement for Lux Toilet Soap. 1958.)

“…despite its repetitive nature, the Lux soap advertisement provided an autonomous space for showcasing the glamour of the female star in Indian cinema through hybrid forms of portraiture… Tracking the Lux advertisement allows us to map the parallel movement of several stars as they appeared on the horizon, shone brightly and faded away, some to be lost forever from public archives and memory.”

- Sabeena Gadihoke, Selling Soap and Stardom: The Story of Lux

In 2010, Tasveer Ghar: A House of Pictures invited scholars from around the world to comment on entrepreneur and art connoisseur Priya Paul’s collection of popular Indian art, which was digitised in 2008. Among them was film scholar Sabeena Gadihoke, whose reading of old advertisements from the collection as well as other sources reveals the fascinating story of popular soap brand Lux and its enduring representation of female stars from various regional Indian cinemas. “Appearing in a Lux advertisement was indeed a ‘must do’ thing for a female movie star in India, a way of announcing her arrival in the industry,” writes Gadihoke in Selling Soap and Stardom: The Story of Lux (2010). Her essay tracks the evolution of these depictions in Lux advertisements, from the time of its entry in India in 1929 to today, through a lens of cinephilia, locating them as extra-cinematic cultural artefacts that “sold stardom more than soap.” She compels us to consider these artefacts not simply as symbols of a history of commodity advertising, but as stories of female stardom in Indian film history. Historical print ephemera, in their redefined role as art objects, find new meanings and modes of interpretation. Gadihoke’s essay thus provides us with an alternative archive of cinema through the visual iconography of female stars.

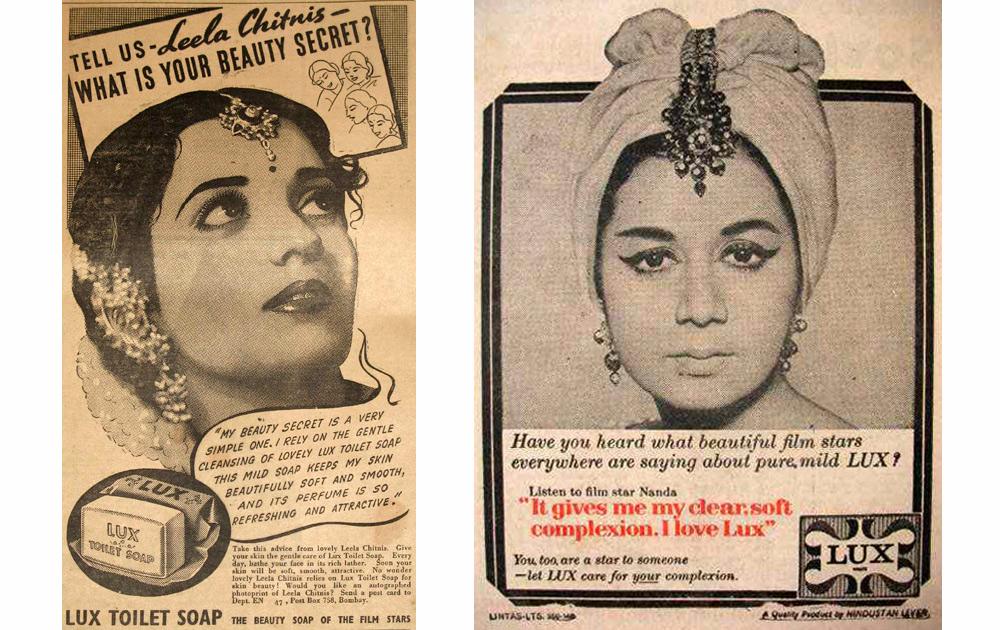

Left: Tell us--Leela Chitnis--What is Your Beauty Secret? (Print Advertisement for Lux Toilet Soap. 1941.)

Right: Listen to Film Star Nanda. (Print Advertisement for Lux Toilet Soap. 1970.)

Early Lux advertisements relied on illustrations: painted portraits of Hollywood and Indian actors, and devotional or mythological imagery that several international and local soap companies relied on at the time. The entry of photographs in advertising culture, however, allowed a shift in the kinds of subjects being depicted:

"…as public women, female performers could provide an easy replacement for celestial models. Photographic indexicality, the possibility of capturing an exact impression of a subject, created a secular identification with other kinds of personhood, particularly the ‘known face’ or the celebrity. Photography allowed for the fixing of identity: it had to be the image of a particular person."

In 1941, Lux began using female stars from Mumbai and other film industries in its advertisements. Several actresses would appear multiple times in the span of their careers, allowing us to trace the trajectory of their stardom through the shifts in their visual styles. Interestingly, the way they were depicted represented the specific phase of their career.

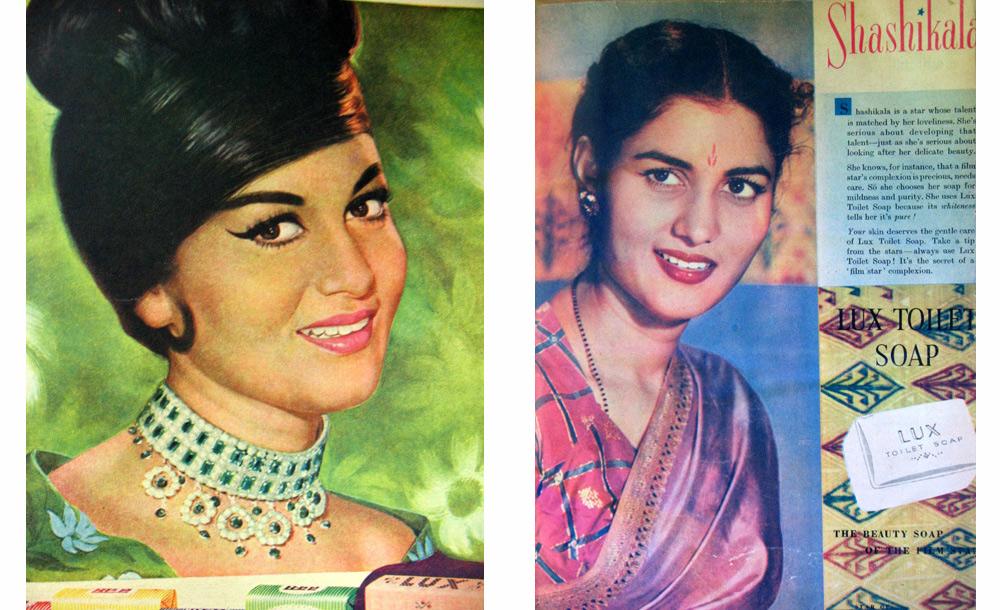

Left: Shashikala, 1965 (Print Advertisement for Lux Toilet Soap. 1965.)

Right: Shashikala, 1969. (Print Advertisement for Lux Toilet Soap. 1969.)

Describing two visually distinct Lux portraits of actress Shashikala from 1965 and 1969, Gadihoke says:

“Since a star like Shashikala appeared in Lux several times during her career, her changing iconography in Lux also gives us insights about the self fashioning of the star image over time. While the actress appears as a glamour girl in (sic) clad in (one figure) there seems to be an effort to transform her image as a serious actresses (sic) clad in a sari in (the other).”

The “fixing of identity” enabled by photography, as Gadihoke mentioned previously, happened at two levels as the specificity of the photographic image in commodity culture served as a vehicle for evolution of the star.

Today, reading photographic advertisements of the past involves several layers of investigation. As they operate within an ecology of cinephilia as objects of what Gadihoke calls “pastiche and nostalgia”—to be circulated in digital forms on social media, sold online and coveted by private art collectors—they allow us to find within them extra-cinematic narratives of stardom and glamour, often missing or limited in official archives. Gadihoke’s analysis of Lux and its culture of celebrating the aura of female stars provides an important inroad into the study of ephemera as an alternative mode of film study.

All images courtesy Sabeena Gadihoke.