All the World’s a Stage: On The Chapal Bhaduri Story

The history of traditional folk theatre across Bengal goes back centuries, with the earliest references to Bhakti processions in the fifteenth century. Locally referred to as jatra, this form of popular theatre involved the use of folk music to drive the plot of the story, which usually revolved around Hindu mythology and local lore. And in the earliest instances, jatra troupes, comprised primarily of male performers, would travel from one village to the next. Given the public nature of these performances, women were necessarily excluded. Indian theatrical forms, at this time, thus relied heavily on female impersonation, which was prevalent across diverse folk and classical art performances such as Ramleela, Kathakali, Bhawai and Jatra. It was only in the 1920s and 1930s that women were welcomed into the fold. Even though this meant the stage was more accepting of women as actors, it resulted in the dwindling fortunes of female impersonators within the popular art form.

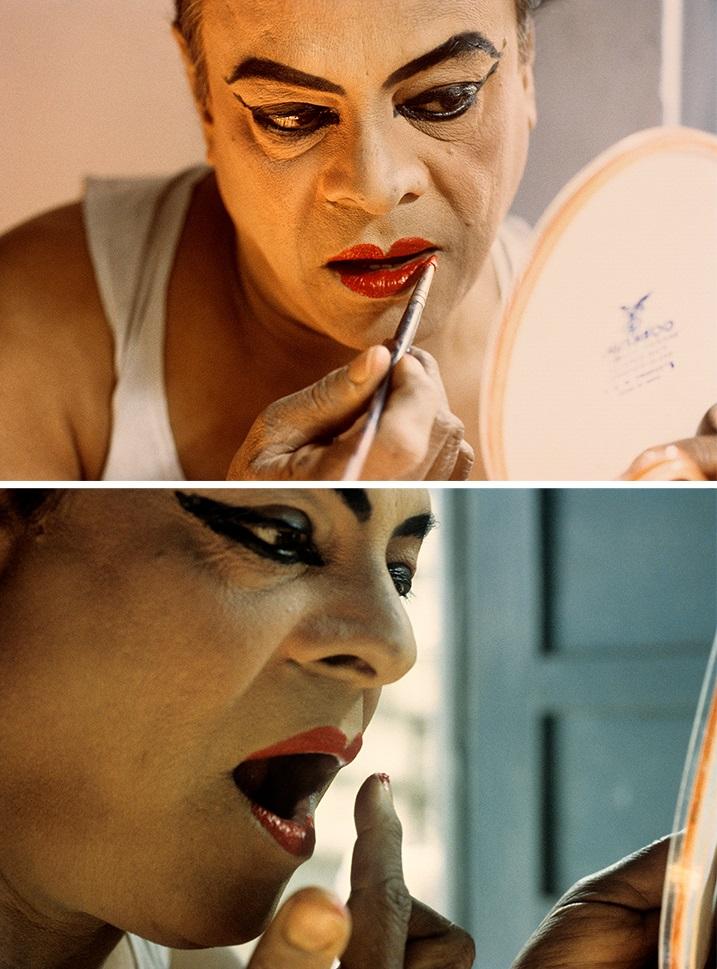

Naveen Kishore. Performing the Goddess, 1999. Digital print on archival paper. Edition of 5.

One such performer was Chapal Bhaduri, also popularly known as Chapal Rani owing to his widely successful portrayal of female characters. He made his debut as a jatra actor at the age of eighteen and remained one of the few actors of his time to continue playing women’s roles on stage, long after jatra’s transformation into what we know as present-day folk theatre. One of his iconic performances was his portrayal of the Devi Sitala, a pre-Aryan goddess traditionally worshipped by several marginalised communities in West Bengal, Orissa, Assam and Bihar. Revered locally as the deity who cures fatal epidemic diseases like viral fever or pox, Sitalapala enmeshes Brahmanical religious rituals with theatrical performance and is usually performed by troupes across the region during the months of March to June.

Performing the Goddess (1999) by Naveen Kishore is an intimate peek into the life and work of Chapal Bhaduri. The performance of gender and theatre are interlinked through the series. A set of images puts into perspective the act of transformation that takes place in the green room, outside of the purview of jatra audiences. The theatre performer’s lived reality—of becoming a woman every night on stage—is the crux of the narrative. The accompanying film, The Chapal Bhaduri Story, with a run time of 44 minutes, shines a light not only on what it takes to physically transition into character each evening but also on the inherent performance of gender when it comes to theatre and, above all, life outside of conventional society.

Naveen Kishore. Performing the Goddess, 1999. Digital print on archival paper. Edition of 5

Sharing anecdotes and performing monologues throughout, Bhaduri owns the screen space he occupies. The actor opens up about his earliest influences, bringing up the importance of play and performance, which were an inherent part of him from childhood. In a sequence, Bhaduri reminisces about his childhood home in Kolkata, sharing how “I would take a cloth and twist it round and round to form a bun. And I would drape a second cloth over my shoulders and start singing.”

Naveen Kishore’s imagery is poignant, as the powerful set of photographs immediately draws one into the story of Chapal Bhaduri. Yet the camera is merely a tool. It is Chapal Bhaduri, with his unflinching devotion to his craft and to each persona that he must portray, that takes centre-stage. Despite a few brief glimpses, the audiences are not familiarised with the actual plays for which Bhaduri is captured transitioning into character. Kishore, instead, focuses on the personal experiences and Bhaduri’s own recollections of his earliest memories on stage. One is privy to his individual negotiations with gender and heteronormative societal pressures and his enquiries into the ways in which gender identities pan out on stage.

Naveen Kishore. Performing the Goddess, 1999. Digital print on archival paper. Edition of 5.

Released in 1999, Performing the Goddess was a powerful piece of queer documentary that was ahead of its time. Offering a critique of the lack of support for the popular art form, Kishore’s series probed the performative nature of gender identity at a time when the LGBTQIA+ community faced widespread ostracisation, especially in the wake of the global HIV/AIDS epidemic. Chapal Bhaduri’s story also raises multiple questions with regard to the lack of monetary support for artists, societal taboos and the current state of the languishing local folk theatre. But above all, it leaves the viewer ruminating on bigger questions around gender and multifaceted identities linked to its performance in the everyday. In bringing together the first-person narrative of Bhaduri along with the series of photos that break down the intimate transformation into character, Kishore humanises the performer in Chapal Rani and the wide spectrum of fluid identities that he so effortlessly embodies. Even though the artist’s focus is on piecing together a portrait of one jatra performer, it is the sense of rootedness in the kitsch that is modern-day India that makes this such a gripping narrative relevant to discourse around gender expression in the country even today.

To read more about the performativity of gender, revisit Anisha Baid’s curated album from Habiba Nowrose’s photographic series and Sukanya Deb’s essay on the lives of mujra performers in Saad Khan’s Showgirls of Pakistan.

All images courtesy of Naveen Kishore and Chatterjee & Lal.