Resisting the Image: The FTII Protests in Kshama Padalkar’s The Strike and I

Kshama Padalkar’s film The Strike and I (2019) documents the filmmaker’s close encounter with the historic Film and Television Institute of India (FTII) strikes of 2015. The students of the premier film institute had organised a protest against the appointment of a new Chairman who was widely perceived as a proxy appointee by the Central government, thus compromising the autonomy of the institution. The film’s documentation of the protests is especially pertinent with the subsequent appointments of actors like Anupam Kher and most recently, R. Madhavan in 2023.

The film employs a mix of diaristic, personal and impressionistic approaches. This allows Padalkar to follow the protest without losing touch with the individual voices of dissent, disagreement, or self-critique that continually informed the protesting students’ actions. A predominant use of voices and faces asserts a stark sense of power over the image of the protest. Cracks in that image—as they unfold over time—are also explored. In a notable sequence, women point out the overwhelming male presence in the protest leadership, including the physical codes of performance during such protests that tend to favour qualities like noise and strength.

The politics of image-making is a part of the problem as well. Students expect a faithful narrative of the events of the protest, which allows Padalkar, as a student of the institution herself, to shoot the events as they unfold. It soon feeds into concerns around surveillance, as the film could become a form of evidence against the administration’s narrative of imagined violence and conspiracy of the students. Some members think the protest’s image needs to break out of an outdated model inherited from the “1960s/1970s”; and a strong concern emerges against being perceived as “political”, “Congress-driven”, or, worse, “Leftists.”

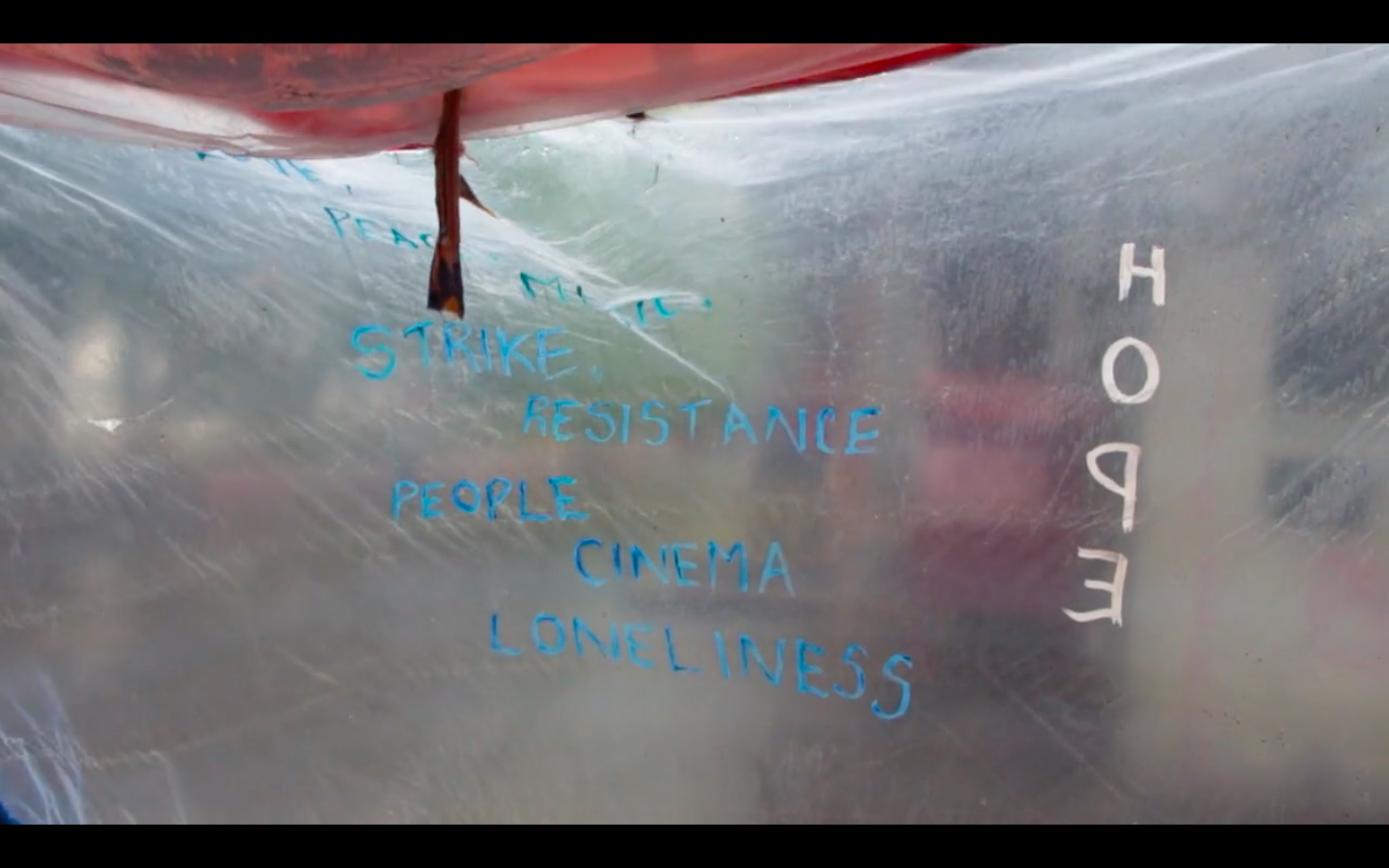

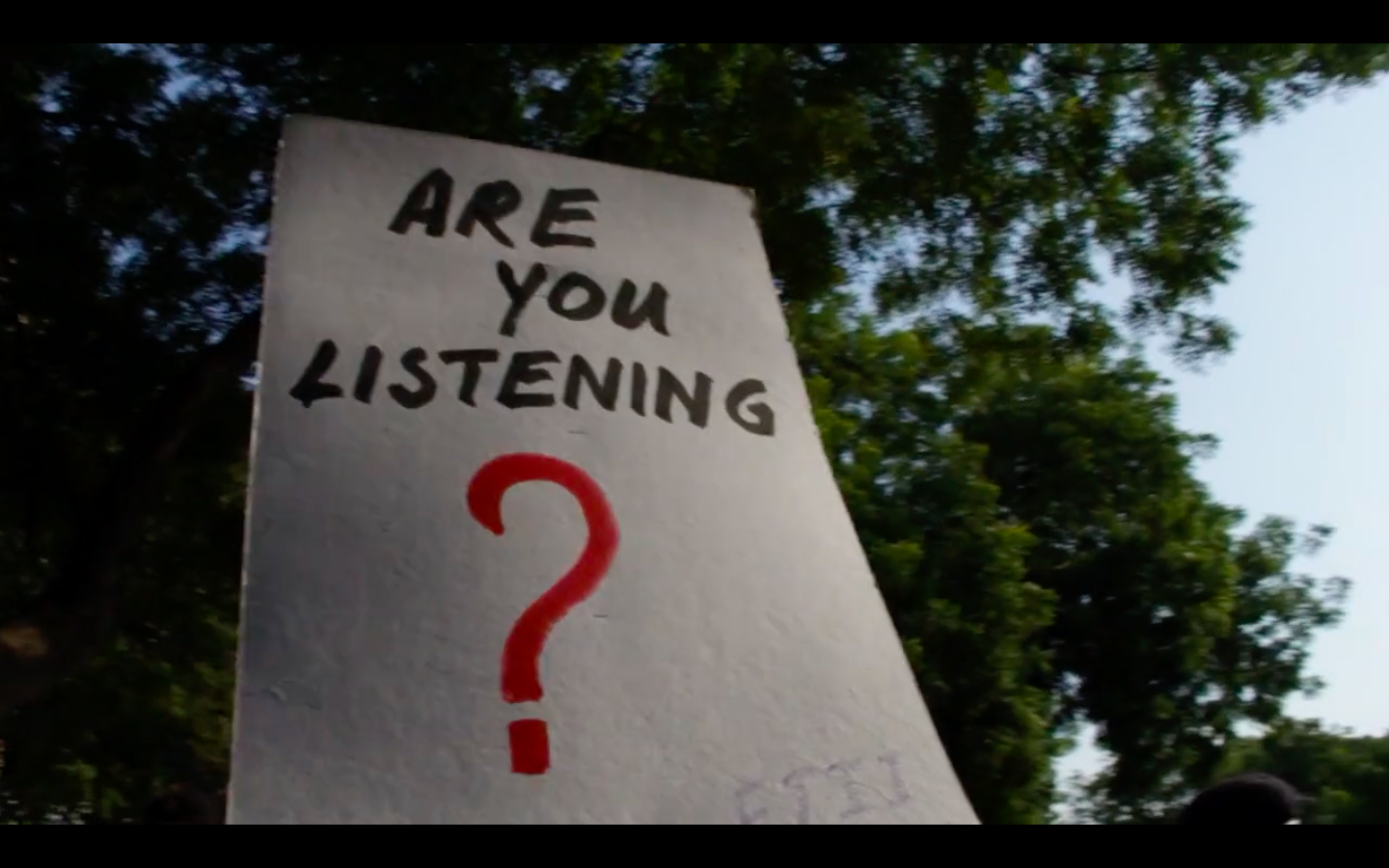

The search for a new image may require the displacement of earlier ones, but the language of the protest borrowed heavily from the atmosphere of debate and opposition, fostered at the time by the actions of the Central government. The atmosphere of dissent emerged as a response to unique identification models (like Aadhar) and the newly elected government’s drive to politically influence institutional bodies in education, culture and information through proxy appointments. Towards the end of the film, as the protest seems to move towards an inevitable decline—in large part due to the mute intransigence of Central government bureaucrats and the Director of the Institute—one might mistake it for an unhappy, “unresolved” ending. But the film’s quiet triumph lies in its ability to show the site of protest as a multi-disciplinary one, encompassing music, painting, poetry and cinema. It puts forth the strong suggestion that these multiple visions, methods and practices are meant to contribute towards a richer understanding of the ways in which the art of image-making has always remained deeply political—whether in the present moment or indeed, “in the 60s/70s”.

To read more about representations of the FTII student protests, revisit Najrin Islam’s reflection on Payal Kapadia’s A Night of Knowing Nothing. The protests also serve as the provocation for Ashish Rajadhyaksha’s public talk “John-Ghatak-Tarkovsky: Taking it to the Streets” hosted by ASAP | art.

All images from The Strike and I (2019) by Kshama Padalkar. Images courtesy of the filmmaker.