Looking Inwards to the Future: In Conversation with Sukanya Ghosh

Spanning painting, photography, animation and the moving image, Sukanya Ghosh’s artistic practice reflects her long-standing engagement with layering, erasure and collage. Her first solo exhibition The Parting of Ways, curated by Rahaab Allana, is on view at the Cymroza Art Gallery in Mumbai until 17 October. Working across a diverse range of found images alongside painting and animation, Ghosh juxtaposes different parts of the image, transforming them into a play of line, tone and colour to a point of abstraction. The artist’s knack for experimenting with layers of analogue and digital images is reflected in the show, as she quips “…new landscapes of criss-crossing meanings and overlapping connections emerge from within these.”

In this edited excerpt, Ghosh enumerates her fascination for all forms of bricolage, new experiments in opticality and the importance of looking inward in order to look forward towards the future.

Shadow lines (Archival silver gelatin photographs with mixed media, 14 x 11 inches.)

Ankita Ghosh (AG): I would like to begin by bringing attention to the title of your solo exhibition. Could you share a little bit about what The Parting of Ways symbolises, and how this connects with the artworks featured within the space?

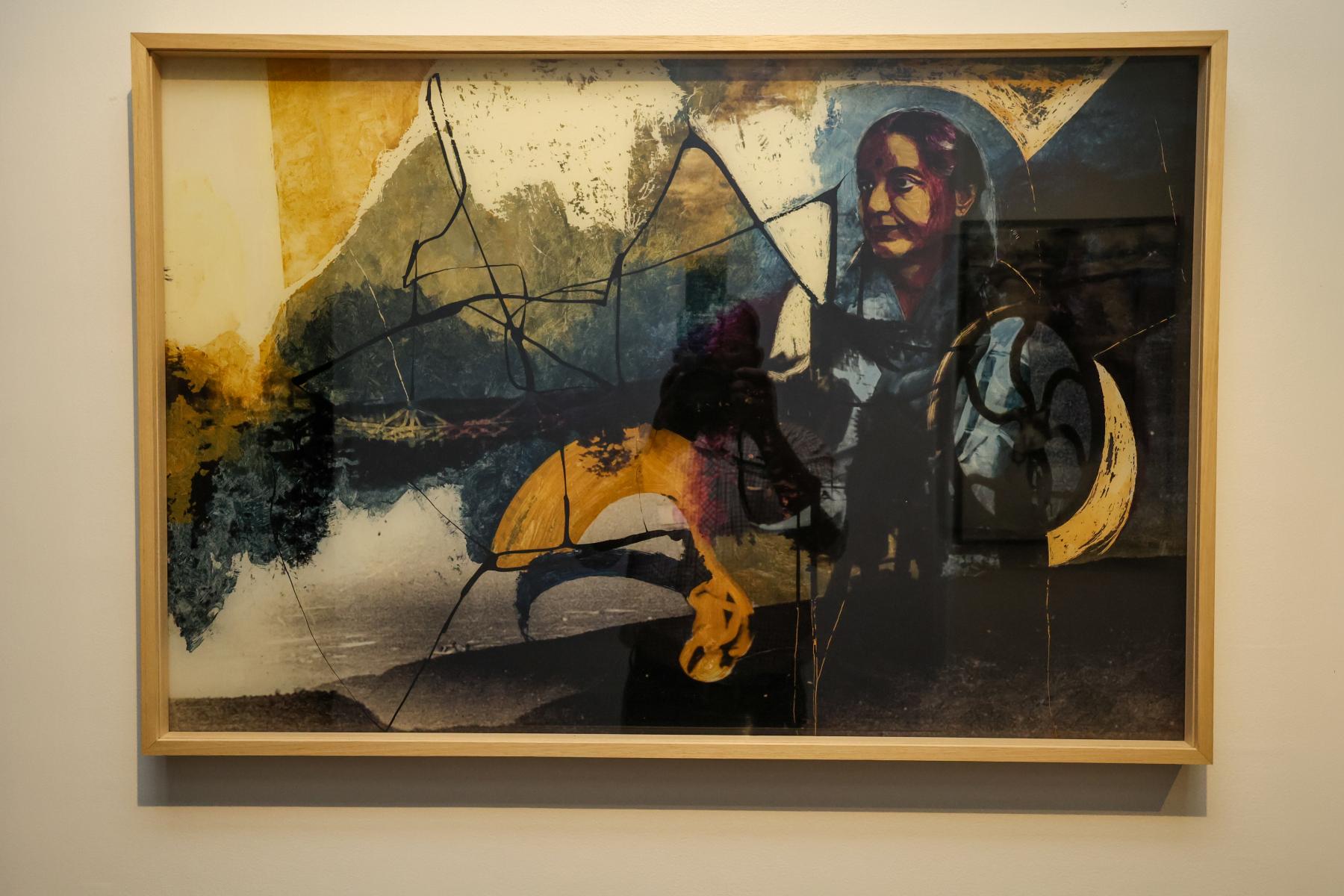

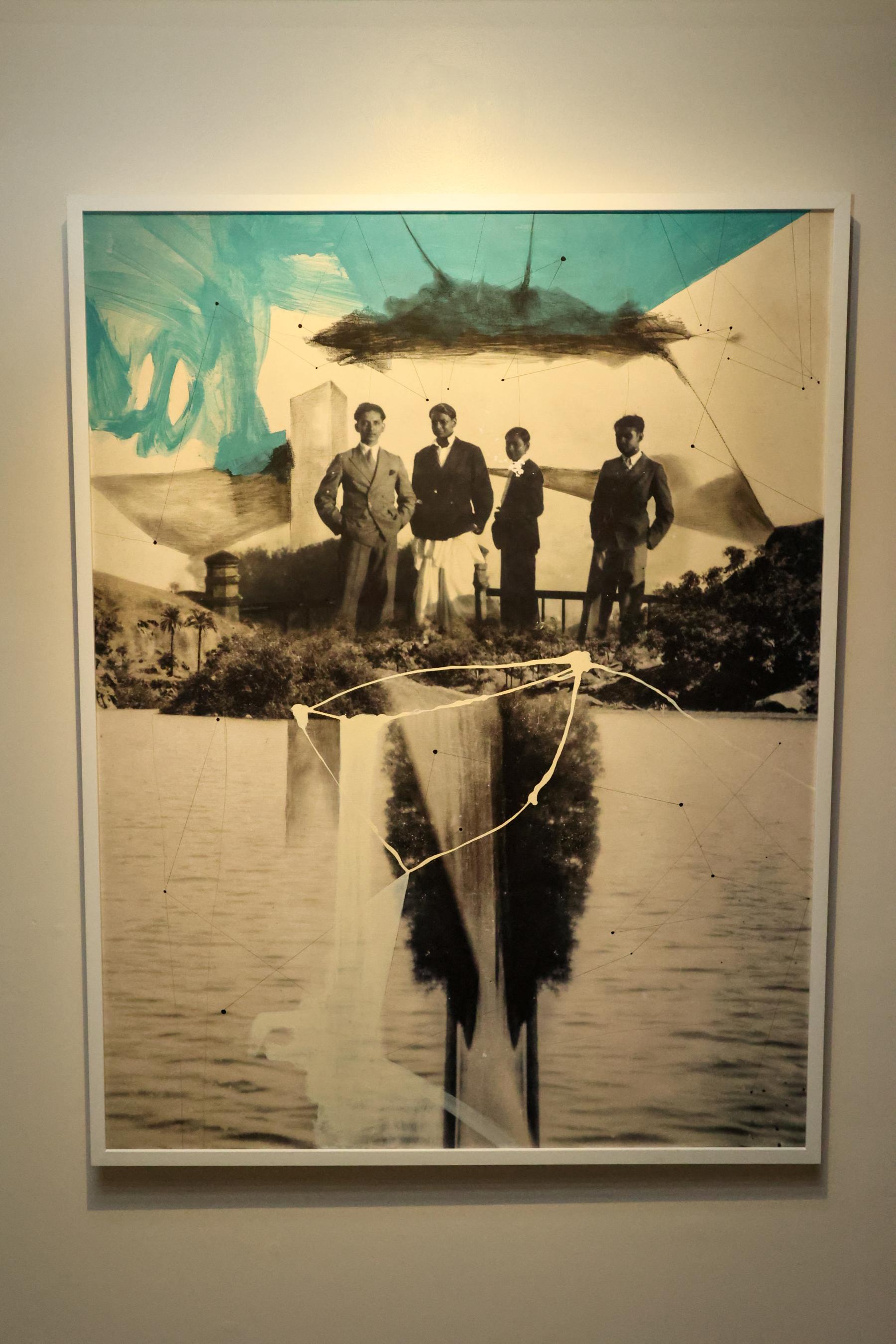

Sukanya Ghosh (SG): This whole idea of working with archival photographs is, to me, a way of working with history in some sense. It is like using these images to create a new context. But what it also means is that there has been a time rupture in the original photographs, in terms of the spectral image. These are events that took place a long time ago. There has been a pause between when these images were originally taken and now, when I am approaching them in a fresh light. This idea of a rupture is a kind of parting from memory. What I am trying to convey is that right now we are headed in a particular direction, perhaps using the elements from the past to reflect on the things that are happening around us in the present moment. Even though it is not an obvious connection, I think it comes across within the body of work I have presented in this exhibition.

I think that is where I keep coming back to in my artistic practice as well—this idea of removing the specifics of time and place from an image and then interrogating the ways in which that particular image changes. What does that change tell us about identity or about location? What does that tell us about how an image is constructed? When I work with multiple images in conjunction to build an artwork, I step out of the intended and associated meanings of photographic images to recreate new possibilities—a sort of “parting of ways” formally.

A lot of the works, especially in this show, are quite figure-centric. In many ways, I have focused on the people within these photographs—many of whom were a part of my family, but I have probably never known them during their lifetime. So, there has been a total disjuncture. We do not know who these people are or what their contexts were at all. In effect, these works try to conjure what I think of as “landscapes of loss,” both in literal and metaphorical senses. There is essentially a parting of ways, a leaving behind, moving away and, by extension, beginning again.

Niley Robi (UV print and reverse painting on acrylic, 24 x 36 inches.)

AG: How did you come across the particular documents that you have worked with in this exhibition? Since these originate from within your family archives, how did they make you feel as you started to incorporate them into your work?

SG: My art practice has always been very much about layering, collage, and using found objects and things. I have been doing that since the very beginning of my art practice. My family also knows this. So, there was a time when we found a whole bunch of these old photographs as my family was cleaning out my grandmother's cupboards. They came across all these photographs that nobody wanted to keep because they had no direct connection to anyone in the family and would probably be thrown away. I think that is when my mother, knowing about my fascination with photographs, decided to hand them over to me.

And then in 2016, I started looking at them with the express purpose of tearing them up and doing some kind of collage work with them. This ultimately led to the body of work I have presented in the show. It has been almost a decade of working with the photographs, because the more I work with them in various ways (and across various mediums), I am kind of going into the innards of it and really exploring all the things I possibly can through this lens. It is still a work in progress, I would say, and I feel like I have a lot more work to do.

The parting of ways (Giclée print on canvas with acrylic and ink, 52 x 40 inches.)

AG: Many of your works are labelled “optical collages”. Could you elaborate on this term, along with the particular methods that you like to veer towards when you work with collages or with found objects?

SG: “Optical collage” is a term that I coined to reflect on the particular kind of work I was pursuing, which often drew on a variety of mediums. I think because I studied animation and have a particular interest in working with images, I thought of creative ways of putting them together—this idea of animation with the sequential image. I experimented with using a single image and stringing it together to make a moving image.

I started doing that, but then I did not want to call it animation because there is so much more that is happening. I felt that the word was not quite able to express what I wanted to convey. Many of these works are installed pieces, so there is a lot of play with light. Then, I thought “optical collage” would describe it best as it references something that is a stream of images, each embedded on layers upon layers, which eventually give way to a sequential flow of events.

In this very show, for example, there are a couple of different formats that I have worked with—I have scanned and used analogue photographs to create digital collages as well as physical collages. I have also drawn, painted, done printmaking, taken UV prints and then reverse point-painted on acrylic. I have sat in the dark room and used some of these old negatives to create different images. So, I would say, my practice spans a variety of mediums, and that is an exciting thing to play with. I quite enjoy exploring these different media and disciplines and trying to see what one can get out of them.

Man, Reflecting: Series : Vanishing Point

(Digital collage archival photo and acrylic paint, 25.25 x 35.25 inches.)

AG: In this particular show, you premise the history of photography in India, its connections with Kolkata and how that shows up in your family archives. Would you like to share a bit more about this?

SG: When I look at the photographs I am working with, I often end up wondering who is behind the camera, what the camera is being used for, and how it has evolved over the years. There are all kinds of images in my archive—from the small, square portraits to big ones as well. I also have a collection of the folders in which negatives would come in. In that respect, of course, it is talking about the history of photography at the turn of the century, as well as access to a camera.

As far as knowing directly however, I would say there is a very great chasm of time between then and now. In many ways, I am unaware of the realities the people in these photographs went through. This is exciting for me because I can give free reign to my imagination and come up with my own interpretations.

I have some studio photographs in my collection, which are, in some sense, posed, but there are also very intimate family photographs. I also have landscape photographs of popular tourist sites. The best part about these images is that, in those days, there was no concept of deleting the photos or editing them to crop someone out or change the exposure. So, there are certain photographs, which I love, where someone’s head is cut off or there is a double exposure. I like the defects or the kind of features that run through the negatives. These things fascinate me, and I enjoy building connections on my own based on what is happening within these photographs.

Jyoti (UV print and reverse painting on acrylic, 24 x 36 inches.)

AG: You mentioned that the ideas of time and location really intrigue you within found objects and images in your artistic practice. Could we unpack that a little more?

SG: There is this idea of the unheimlich, which I keep coming back to because I love that word. It was used by Freud to talk about the spectral or the uncanny. It caught my attention because this is exactly the kind of thing that I am building into my works, where you see something that is familiar but at the same time there is a strangeness to it.

There is something that is odd, inverted or skewed within these images, even though they look like run-of-the-mill family photographs. For me, each image is constructed with multiple photographs meshed in various different ways. There are interventions and interpolations with ink, paint and much more. So, the feeling you get is of the uncanny. It is something that is recognisable, but maybe not; it is familiar, but not the same.

In many of my works, one may think they see something familiar. However, upon looking closer, it becomes much more layered and not exactly what one expects. These are things that I like to play with because, in many ways, I try to question the kind of history they originate from, or the idea of memory or recollection. What we remember is always augmented and informed by our lives and our interpretation of certain experiences.

Similarly, and especially in this milieu, where we are rewriting history literally around us, my work is an exercise in re-imagining the past in many ways. When I am working, I am also aware that I can reconfigure the past and use my practice to talk about the present. Whether it is in terms of geopolitics or personal identity, who we are and where we come from are universal questions that everyone has at some point. And archival photographs are quite universal across time and space. Be it in terms of quality, identity, or historicity, all of these things tie into the work I do with found images within my practice.

Often, it is not just an exercise in nostalgia but also about probing our own history and the ways in which we look at it. And while it is very intensely personal and intermittent in many ways, it is also communal in that it speaks to many people in different ways. There is an interplay of media and its many entanglements with history, geography, style and space. The process of creation, then, is a formal experimentation with media, of which I am the agent.

L to R: Pheroza J. Godrej, Sukanya Ghosh and Rahaab Allana.

To read more about Sukanya Ghosh’s work, revisit Mallika Visvanathan’s reflection on the use of medical imaging in three video works screened as part of the VAICA festival.

All works by Sukanya Ghosh. Images courtesy of the artist, Cymroza Art Gallery and Godrej Archives.