Chronicle or History? Looking at Anglo-Indian Photography

.jpg)

Book Cover of Irwin Allan Sealy's The Trotter-Nama.

Indian literatures in English and the vernaculars contain a potent archive of thinking on photography. Through fiction, voices can be manipulated in creative ways to make a reader see what they are looking at when they approach narratives—whether of nation or a community. Through a series of posts here, we will examine how literary representations of photography influence our understanding of the practice and its social history among several communities in India. Along with fictional texts, we will also look at individual or studio practitioners who have made an impact on these ideas.

The evolution of sophisticated visual technologies—in writing and practice—was accompanied by a need to fill gaps in the archives of national memory by the end of the 1970s and ’80s in India. In these accounts, the Nehruvian consensus was fragmenting under the oppressive pressure of a national memory that was increasingly getting homogenised by a dominant, cultural imagination of Hindutva. Under this rubric, several minor traditions were losing their singularities. The famous generation of 1980s novelists included writers like Irwin Allan Sealy and Salman Rushdie who insisted on expanding these archives, while using frivolous, ludic narrators to show what this melancholic condition of hyphenated belonging meant to several Anglo-Indians in their own nation. Sealy, in fact, revises Rushdie’s more famous novel Midnight’s Children and suffuses the Indian national imagination with the historical condition of the Anglo-Indian in The Trotter-Nama. And in his account, the lead is taken by the image over the textual traditions of historiography:

"This foul substance is called what?

The foul substance is called History.

And its opposite?

Is the Chronicle.

Which may be illustrated?

Profusely.

Is colourful?

In the extreme.

Has flavour?

Honey in the mouth, honey in the belly…”

For Eugene, the narrator of this novel, attempting to piece together the excessive, unruly chronicle of the Trotter family into a linear narrative, perspective is central to the issue of writing. With his unhistorical chronicle, however, he also means to realise the loss implied by the transition from the miniature to the photographic studio. And so, there is a mocking lament at the passing away of miniature:

“Who killed the (miniature)? When? What was the weapon?

Full marks—the camera. The nineteenth-century camera, and behind it the Montagus of this world. Dry, literal, joyless, prowling shutterbugs. Smash their cameras for them and you get no gratitude. Instead of kissing you and embracing the world, they creep off somewhere and grow another.”

The slipperiness of seeing in miniature, giving one the ability to detach vision from perspective, is the syrup that is lost and lamented in Sealy’s novel of mock-nostalgia. This ironic narrative of "loss" informs the anxiety around cultural authenticity which relies on singular sightlines of community and belonging. When we gained our sense and practice of a singular perspective, Sealy’s narrator seems to imagine, we also lost our ability to be many people at once.

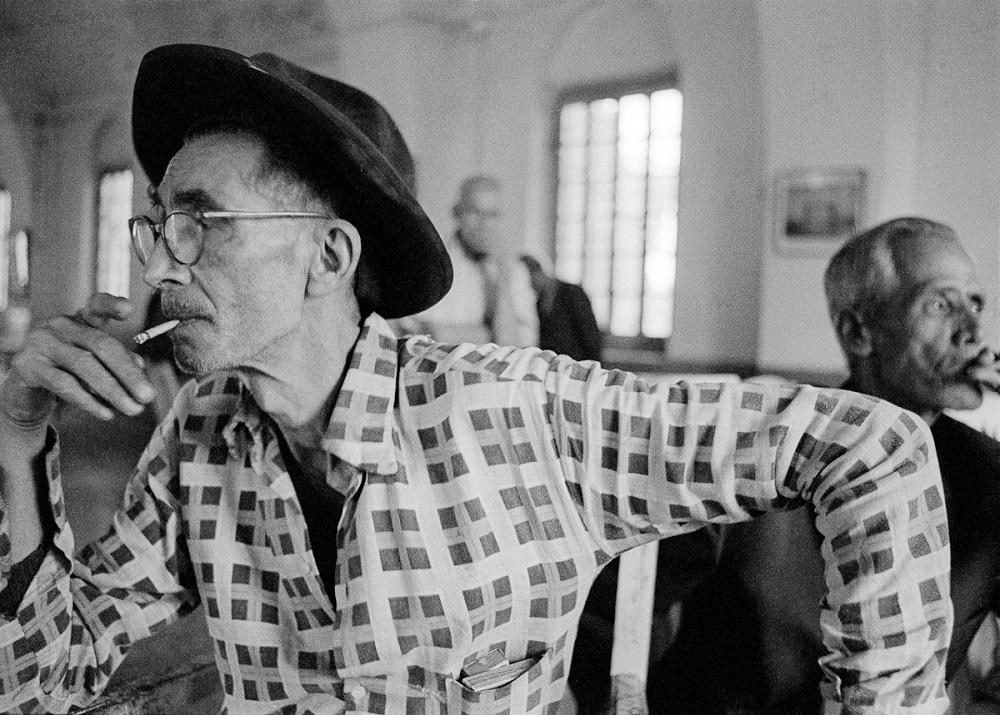

Mr. Carpenter. (Photograph by Karan Kapoor. Kolkata, 1981. Silver Gelatin Print. Courtesy of Tasveer.)

The early Anglo-Indian photographers who took to the camera were not only the dry Montagus of the world, whose “...appetite for photography grew until he began to stink of bromide as well as ammonia… (as he) hunt(ed) for objects to wave his lens cap at.” It passes eventually to fit comfortably into the social performances of Alex Kahn-Trotter, for whom it symbolised a part of living an easy, colonial lifestyle—photographing gardens, porticoes and pillars, while enjoying the parties thrown by the elite of Nakhlau.

But Kahn-Trotter’s images soon begin to get suffused with the ominous marks of memory struggling for rational definition:

“He was tolerated because of his name and connections, but then certain telltale clouds began to loom. There were never any in the blue skies of his canvases, but when he developed the photographs there invariably hovered, just above the subjects’ heads, a small blank balloon sometimes with a trail of tiny bubbles leading up to it, as if the whole company were posing underwater and someone had let out a breath. At first the clouds were easily disguised (Alex put them down to grains of silver on the photographic plate) but later they grew bigger and more numerous, eventually turning into blotches and smears that would spell, among other things, an end to his second career.”

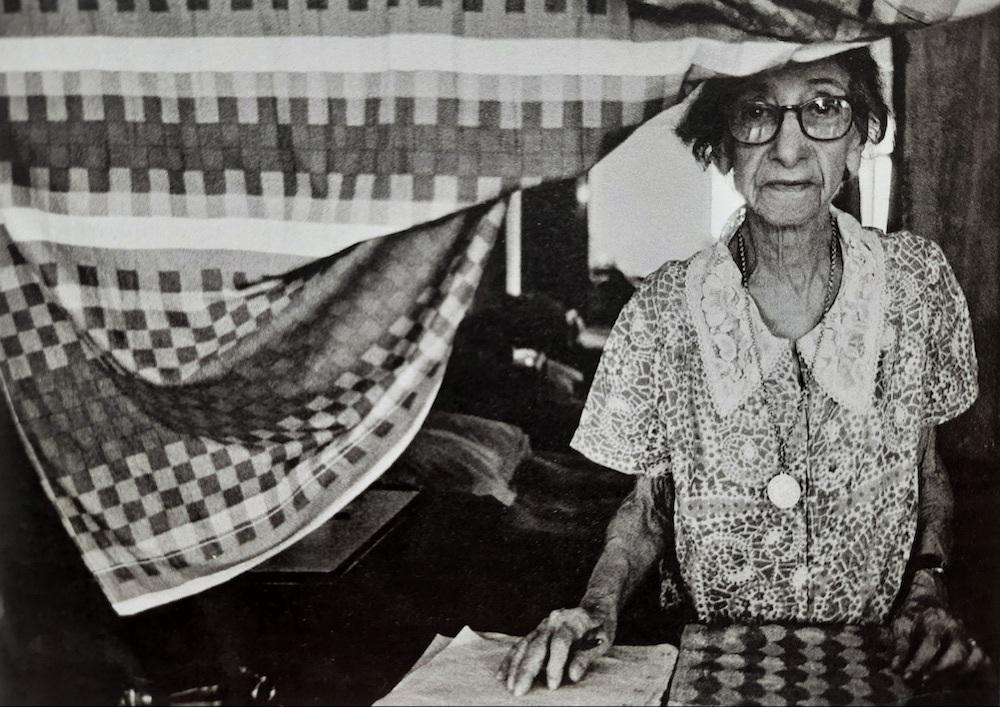

Andheri, Mumbai. (Photograph by Karan Kapoor. Mumbai, 1981. Silver Gelatin Print. Courtesy of Tasveer.)

Memory gets submerged, as blotches and smears render the image illegible and unworthy of attention. The community holds its breath as the archive bristles against its presence, which has always troubled the imagining of the nation in terms of the expression of some "homogeneous cultural authenticity."

To read more about Anglo-Indian photography, please search for "New Practices of Narration: Looking at Anglo-Indian Photography" in the Stories section.