Reading the Body: In Conversation with Sandeep TK

Exploring his caste, class and queer identity through photography and moving images, Sandeep TK presents the personal as political in a confident, playful way. Radiating a raw emotional vulnerability, the artist’s work draws attention to his world and his experiences—from what it meant to grow up as a queer person in a small town in Kerala, to living as an artist in Bengaluru. He considers much of his work as ongoing, necessitating a process of revision and reflection on who he is as an artist and as a person. In this edited interview, Sandeep speaks about how he developed his practice, his approach to photoperformance, engaging with forms of representation and critically examining the world around him.

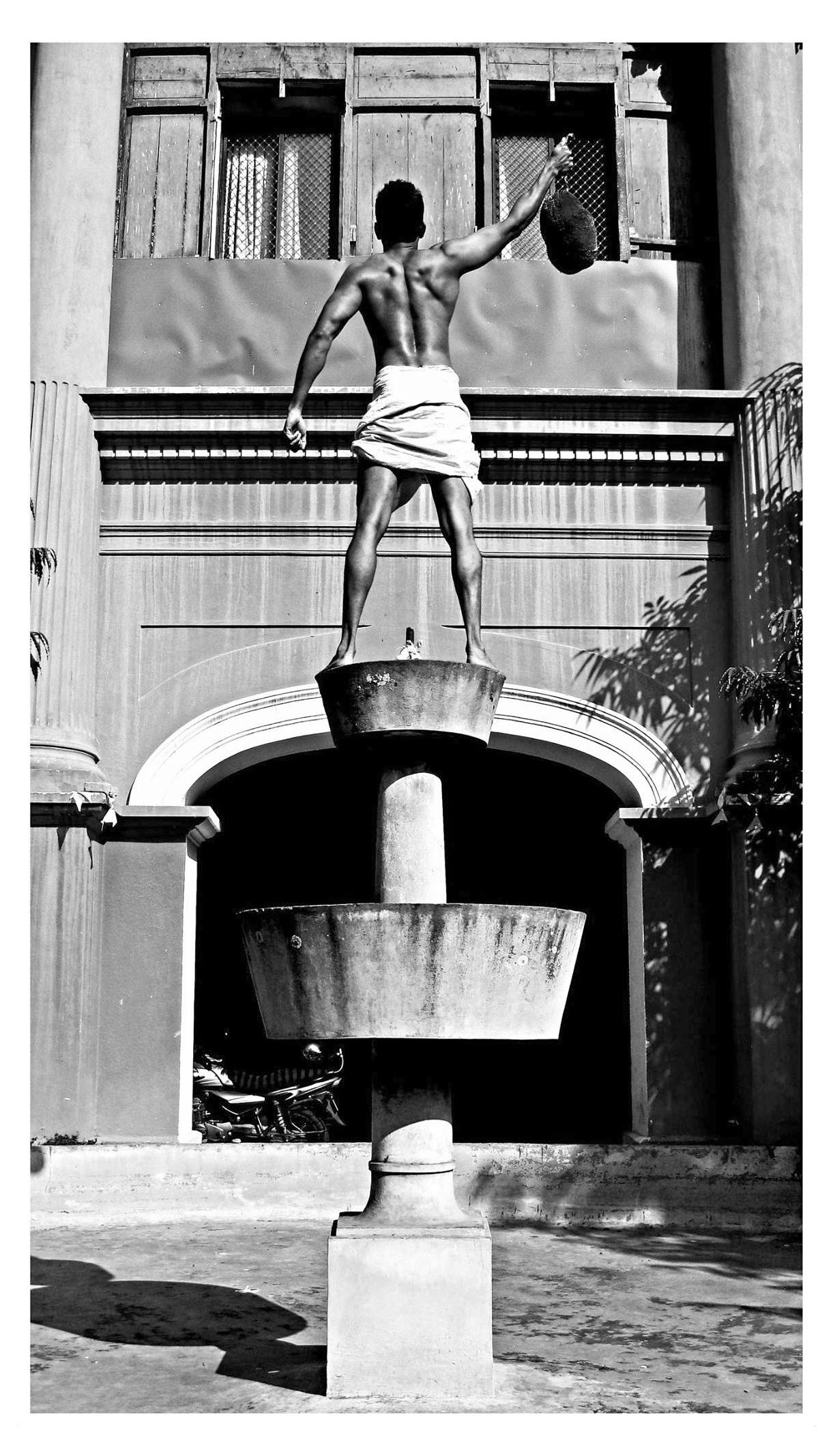

Toy boy from Malabar and his journey to wine cheese and chocolates (2023).

Mallika Visvanathan (MV): A strong motif in your practice, the body appears to be both liberating and restrictive. How do you approach the idea of the body, especially the queer body, in your work?

Sandeep TK (STK): For as long as I can remember, I have wanted to be a visual artist.

I was raised in a loving, working-class family in a small town on the Malabar coast of Kerala. My father had a government job but was asked to retire from it when I was six-years-old. My father found it difficult to do menial jobs because he was educated, so we struggled to survive financially. Geographically and culturally, we were a long way from any metropolis, even in Kerala. We were also lower caste—even though I did not fully understand that while growing up, since everyone around me was from the same caste as I was. As I moved away from home to Hyderabad and then Bengaluru and beyond, I began to slowly realise how much of an outsider I was in the sophisticated world of art and culture.

And so, I wanted to create my own identity and display myself in a way that brings recognition and respect to me—to my body, my class, my caste and my humanity. I had this strong sense that I deserved a place in the world of art, and I wanted to make it myself—without listening to the orders and commands I used to get at the beginning of my journey.

Years ago, I went to the opening of a photography exhibition in Bengaluru. I did not feel like I belonged there, I felt no connection to the visitors, the space, or even the artist, and I certainly did not have the confidence to talk about the work. But I felt a deep connection with some of the models in the photographs—dark, muscled boys—and the settings they had been placed in. I thought they must be from villages. And then I started thinking about who these boys were, what kind of work they did, why they decided to pose for these photographs— had they photographed themselves instead, would the works would have ended up exhibited in a white cube?

That same year, a photographer approached me to pose for him. He wanted me to stand in the street and flex my muscles, wearing only my underwear. I asked the photographer to pay me a fee, and he found somebody else to pose for him for free. That was when I decided I would rather do this on my own. I began to photograph myself for the series that eventually became Let me add something in my own melody (2022) to tell my story—and the stories of people like me.

I am queer, and much of my work is informed by this aspect of my identity. I push my body to be perfect, I want to be desired, and I strive to meet the standards set by popular media, and yet I realise that my body also carries the marks of physical labour, the stains of belonging to the wrong class and caste, which, I suppose, contradict my efforts to be perfect. I play with the tension between these contradictions, which I find simultaneously liberating and restrictive.

Let me add something in my own melody (2022).

MV: In Let me add something in my own melody, you have accessed archival letters to recreate photographic history. Can you tell us a bit about your process of engaging with the archive and how this project evolved?

STK: The Basel Mission was an influential missionary organisation in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, and it played a significant role in the Malabar region, where I am from. Some years ago, through a Pro Helvetia residency, I had the opportunity to spend some time in their archives in Basel.

Going in, I was not sure what I was going to find. The Basel Mission was a Christian missionary operation, a European venture with all the imperial overtones of the time. But they did bring fresh eyes to the region and could see the situation of untouchable castes for what it was: oppression. And to the extent they were able to help, people were grateful, however much the exercise was propelled by the fervour of religious conversion and the civilising mission. As someone from the same untouchable castes they affected, from a family that did not convert, I had an understandably complex reaction to their legacy in my homeland.

To my delight, the archives ended up exceeding my expectations. I found hundreds of letters written in Malayalam, from people in the Malabar region, recounting their experiences with the Mission. Currently, I am creating visual representations of these letters and playing with words I found in them, because I find that much of the meaning expressed hundreds of years ago is still resonant and lends itself to a dramatic, poetic and poignant set of expressions.

Let me add something in my own melody (2022).

MV: How does Kerala as home invest itself in your work since you have been living and practising in Bengaluru for the past decade?

STK: I deeply love Kerala but do not call it home. My memories of Kerala are pleasant and filled with my parents and family and the friends I grew up with, but I am aware that my upbringing did not give me enough to be able to break free and become the person I aspired to be.

I also do not call Bengaluru my home. Bengaluru—as well as some of the other cities I have been lucky to visit—gave me the material to grow by exposing me to mentors, lovers, friends, well-wishers, ill-wishers, and more, including heartbreaks and breakthroughs. Above all, I suppose, Bengaluru gave me access to the kinds of discourses and institutions I needed to expand myself and move up in the world, something I am not at all ashamed of saying I sought and achieved. I am grateful for the mobility I have had and for every opportunity I have received.

Now, Kerala is the place I go back to in order to relax, and Bengaluru is the place that excites me and gives me hope. Both places are a part of my existence; Kerala gave me the questions and Bengaluru provided me with some of the answers.

How are you? I am fine (2019).

MV: How does photoperformance as a form allow you to think of and question the representation of marginalised identities?

STK: The scenarios I create in my photographs are not alien to me. Some of the portraits I made for the series Toy Boy from Malabar (2023) come directly from my experiences, so staging them was not difficult. However, the series is not solely a representation of what I experienced as an individual, but rather a distillation of the collective experience of other people like me, of outsiders to the world of cultural elites, of people from the wrong castes and the wrong class. Of course, not everyone who has stood on the outside is ready to talk about their experience because it often involves pain, but for me, photoperformance as an art form has been a little like talking to a therapist. Therapy is a privilege, and I feel like I bought myself access to it long before I could afford actual therapy by playing around in front of the camera and restaging events from my life—except, this time, on my own terms.

Photoperformance has also allowed me to take my own experiences seriously without waiting for anyone else’s permission to do so, to give my life value, and to express it, aesthetically, poetically and confidently.

Let me add something in my own melody (2022).

MV: While all your work is personal, text and writing in the form of diaries, conversations, or memories often add a powerful layer to the image. Toy Boy from Malabar and His Journey to Wine Cheese and Chocolates, which was recently showcased as part of the Serendipity-Arles Grant in 2023, draws on your diaries to critique the jargon of the “artist statement.” Can you tell us about your approach to the role of text/writing in art?

STK: Toy Boy from Malabar is about the excessive flaunting of art-world jargon to some extent, but it is also about the projections so many of us employ to create an elevated impression of ourselves. It is about the power of articulation and image-making, as well as the dense layers of privilege, training and confidence that lie underneath it all.

It is about my own resentment—and, if I am being perfectly honest, envy—of the kind of people who grew up with libraries in their houses and the kind of people who seem to have lived their entire lives as libraries.

When I first started making photographs, I did not have the confidence to show them to anyone. And when I was allowed to show my work to someone I admired, I did not have the vocabulary to articulate what the work was about. For a while, I stopped taking photographs and instead started writing about the photographs I wanted to take.

Now, writing has become an important part of my practice. I do not take images every single day, but I do write down a few sentences every day. And when I have enough words, I take a break and translate them into photographs. I am working on myself to be able to convert instinct into articulation; to give my work the depth and meaning I feel deep inside and have always known was there, but which, until recently, I have not been able to describe in words.

Toy boy from Malabar and his journey to wine cheese and chocolates (2023).

To learn more about the Serendipity-Arles Grant in 2023, read a short report on the exhibited projects. To know more about other artistic interpretations of the photoperformance, read about the works of Anoli Perera and Habiba Nowrose.

All images by Sandeep TK, courtesy of the artist.