New Practices of Narration: Looking at Anglo-Indian Photographs

The 1980s were the decade in which both Sealy’s novel The Trotter-Nama (1988) and Aparna Sen’s film 36 Chowringhee Lane (1981) made an impact on the representative traditions of and for the Anglo-Indian community. In Sen’s film, this is realised as an image of isolation and imminent obsolescence. Jennifer Kendal’s Miss Violet Stoneham is presented to us as a member of a community in decline. The community’s lack of social power makes it easier, it is implied, for Miss Stoneham’s life to be ravaged by the careless attentions of a bickering middle-class Bengali couple that relates romantically and destructively to her legacy of culture and care. Images of Miss Stoneham, surrounded by the melancholic objects of her life in her small flat at the film’s address, allow us to see the photographed space in continuity with her decline. This is one of the hard stereotypes of Anglo-Indian representation, an image-trap that Sealy aspires to break out of by embracing the plural visions of a more peopled history of the community, rather than emphasising their disjunction from the social lives of other Indians.

Jennifer Kendal as Miss Violet Stoneham in Aparna Sen’s 36 Chowringhee Lane. (1981.)

In its final oneiric images of erotic fantasy and repressed possibilities, the film takes a leap into filling the silent archives with the possibility of an excessive, proliferating counter-archive of dreams and abstraction, rather than narrative resolution. These dream images are difficult to appropriate for a programme of radical political identity to emerge; but they do something more ordinary by submitting the individual to be a repository of community culture that cannot be reduced to scientific, documentary evidences of identity.

Miss Stoneham’s dreams suggest an unruly archive of impressions and energies that cannot be reduced to a narrative of simple political history. (36 Chowringhee Lane. Dir. Aparna Sen. 1981.)

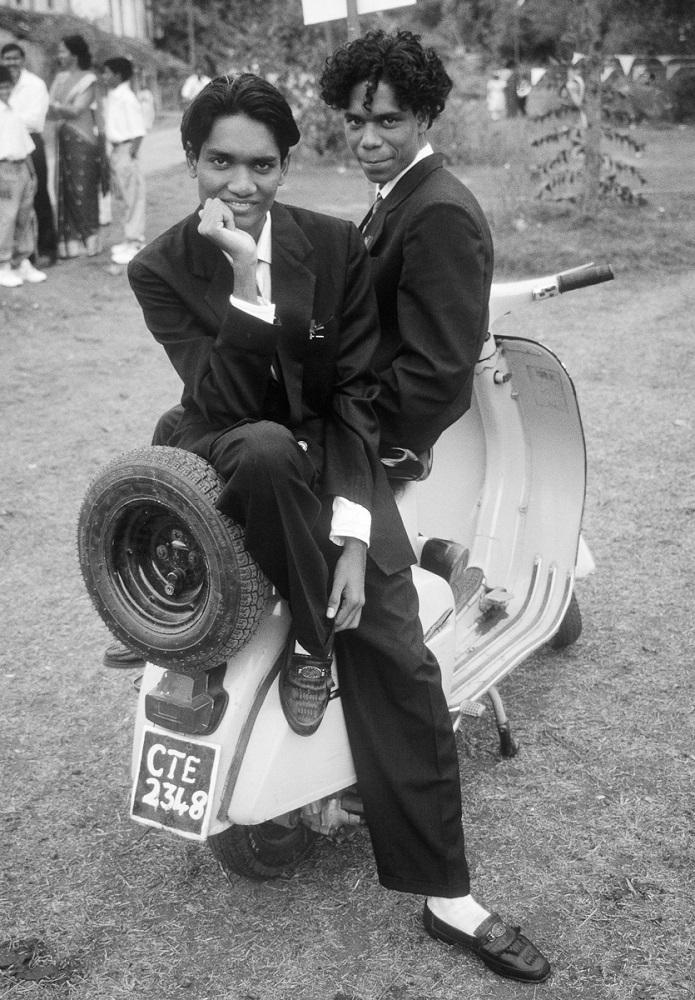

Several photographic projects grappled with and against these processes of fixing the image of the Anglo-Indian community. Karan Kapoor made photographs of the communities in Catholic Goa and Kolkata of the 1980s and ’90s. He belongs to the community not just due to his identity but the effort he makes to ingratiate himself with his subjects, seeking to involve himself in their social lives and rituals: like when he photographs a couple of friends at the Three Kings Feast in Goa.

Three Kings Feast in Chandor, Goa. (Photograph by Karan Kapoor. Goa, 1994. Silver Gelatin Print. Image Courtesy of Tasveer.)

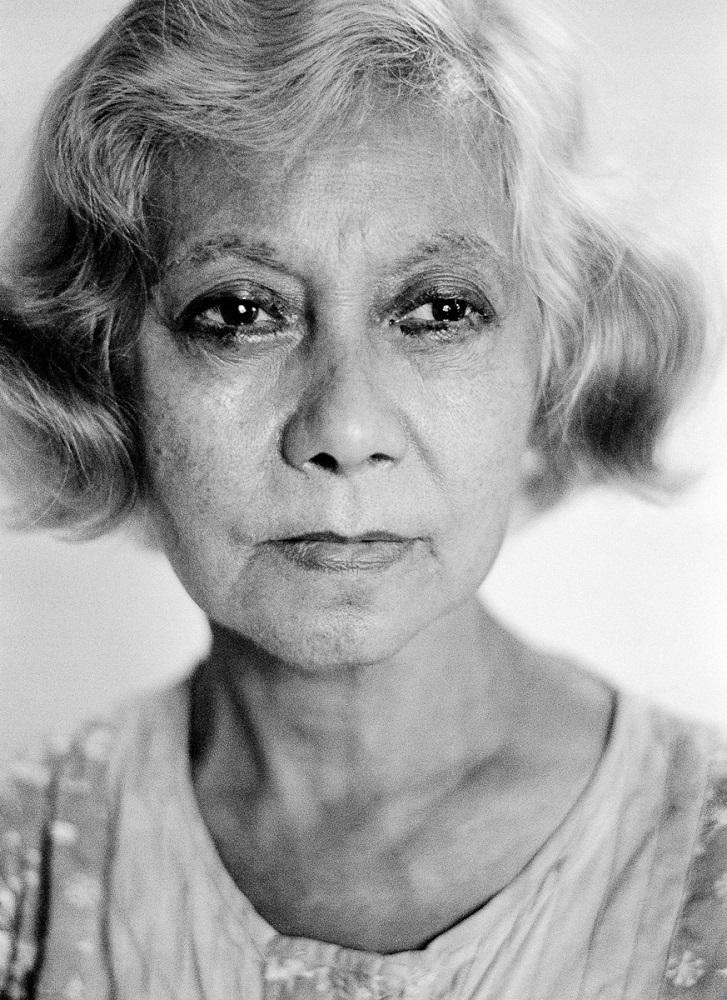

Photographing younger members of the community and older ones—leaving out the teeming and busy middle-aged ones—allows for several stark, polemical contrasts: dreams on the verge of articulation on one hand, fantasies curdled by time on the other. As part of the second trajectory, Kapoor also photographs an Anglo-Indian lady (Violet) in the early 1980s who resembles the image of Miss Stoneham in Sen’s film. They belong to the same community of images as well. However, the close-up view of her face is not softened by the production design of 36 Chowringhee Lane, and this is not a simple story of isolation or abandonment. The traces of the eyeliner are flaky but resolute, the determined set of the lips suggest a life populated by decisions taken rather than passively watching agency vanishing from her grasp.

Violet, Andheri, Mumbai. (Photograph by Karan Kapoor. Mumbai, 1982. Silver Gelatin Print. Image courtesy of Tasveer.)

Even as images like these put the burden of the whole community in a singular frame, the individual subjects find their own way to avoid the fixing gaze of the photographer: either by turning away to take a casual drag from a cigarette or dressing up the self in ludic ways to keep open the possibilities for continued self-transformation in a modern republic, especially at the threshold of youth.

Loutolim, Goa. (Photograph by Karan Kapoor. Goa, 1994. Silver Gelatin Print. Image courtesy of Tasveer.)

If you would like to read more about Anglo-Indian photography, please search for “Chronicle or History: Looking at Anglo-Indian Photography” in the Stories section.