Leavening the Image: Reflections on Weather Report with Tenzing Dakpa

There is a certain texture to the collisions and tensions produced when photographs interact with the spaces in which they are exhibited. It is interesting to think of how images intersect with form and formulation, how they are further brought together in conversation with other mediums, and how, among all this complexity, the installation takes shape.

Weather Report, a solo exhibition by Tenzing Dakpa, opened at Experimenter – Hindustan Road, Kolkata on 24 May 2024, showcasing two significant bodies of work by the artist; both emerging from his responses and relationship to his immediate surroundings. The works on display—Manifest (2023) and Weather Report—detail Dakpa’s experiments with photography, made evident by his fascinating use of gestures, forms, scale and surface.

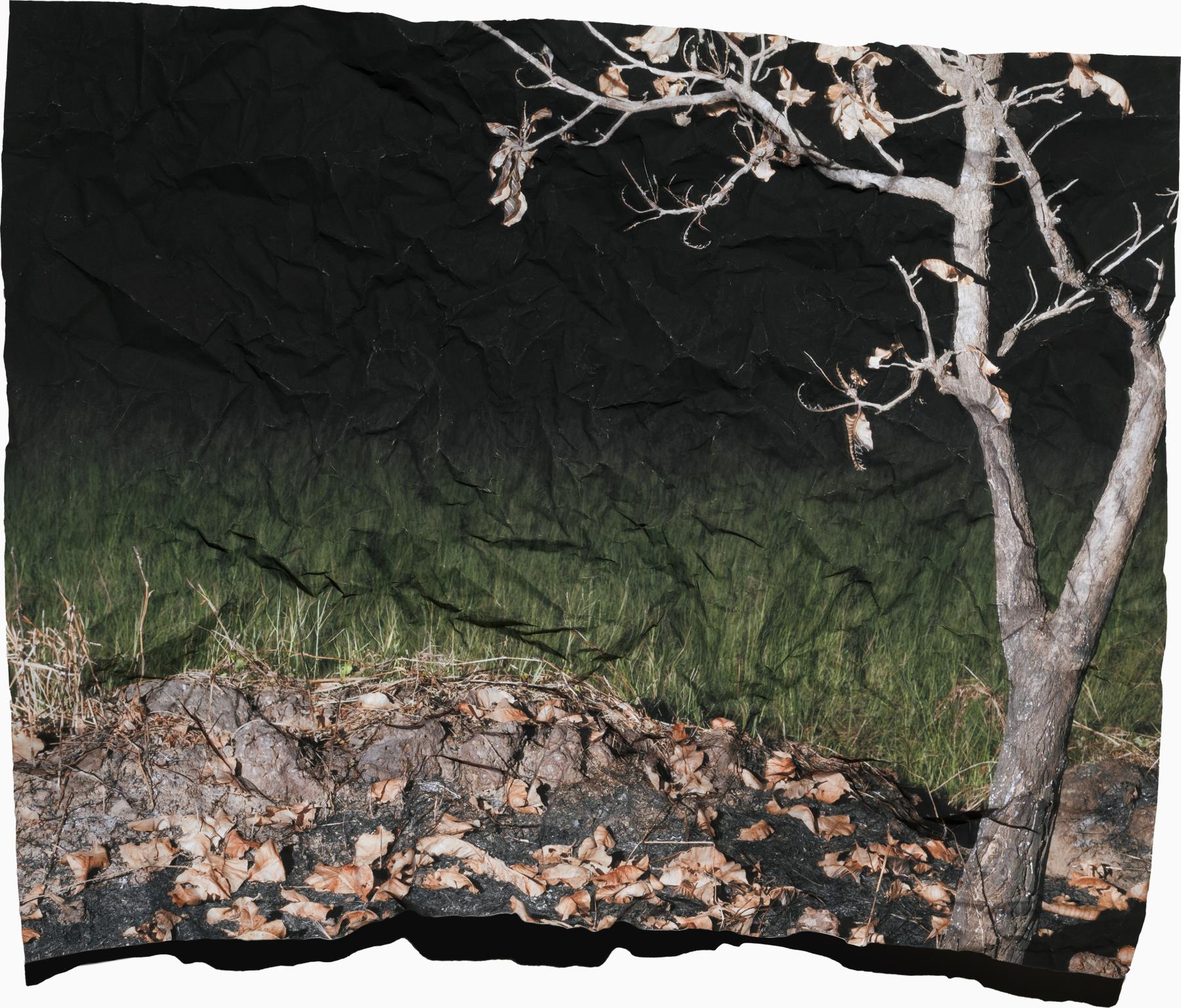

Manifest I (2022. Archival pigment print, 16 x 20 inches, 40.6 x 50.8 centimetres).

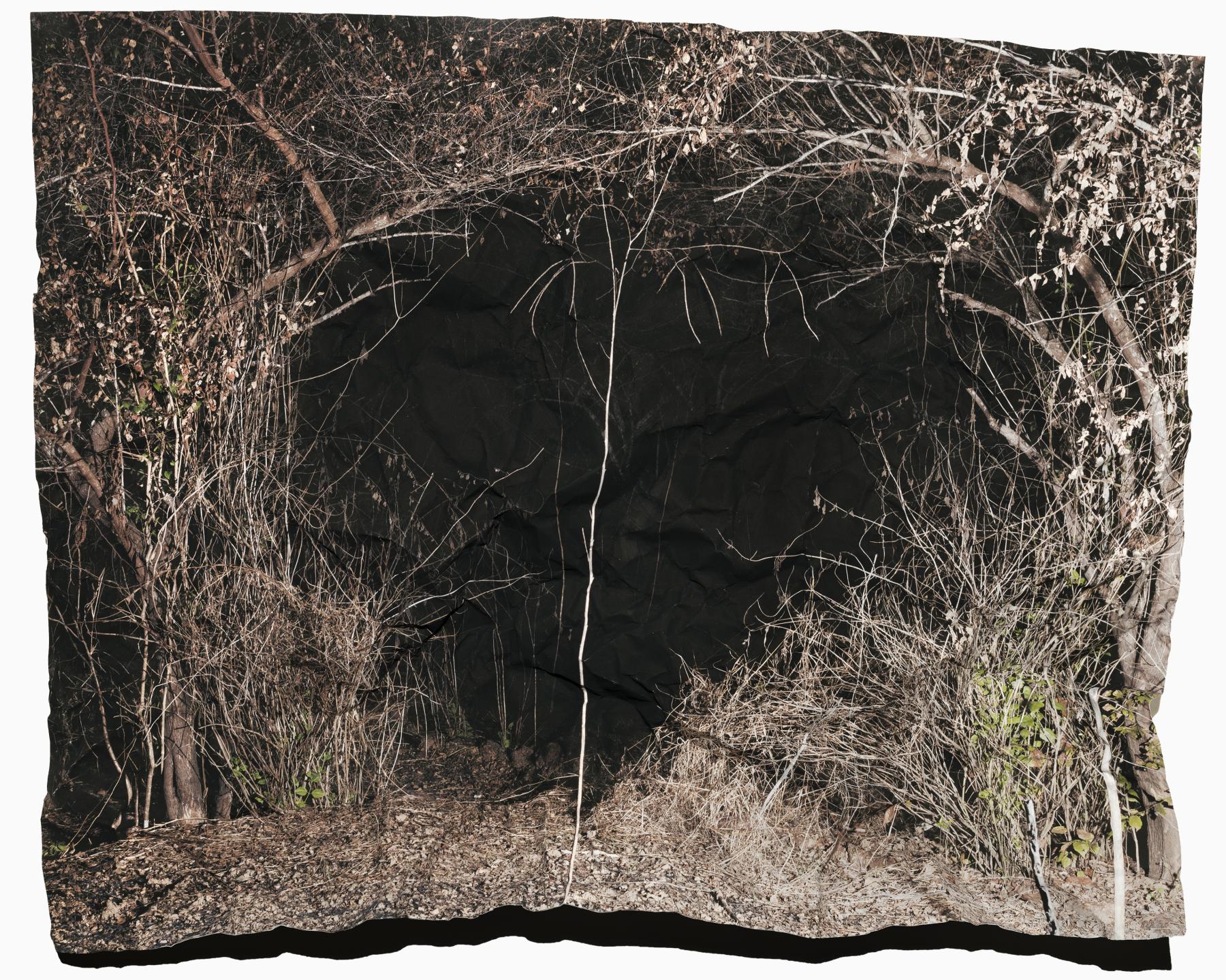

With a considered approach to dialoguing with the contemporaneity of the photographic medium, Dakpa’s process with the camera showcases his immense ability to observe with great intent. With Manifest, we are made witness to the aftermath of forest fires in North Goa, evidence of human-made devastation. Photographed by Dakpa, the images reveal his return to these familiar sites with profound introspection. The photographs—rendered in pigment ink on acid-free paper—are subject to a very specific kind of (post)processing; acts of crumpling that evoke not just the undulations of its topography but also the disruptions inflicted upon it. The liminal space between creation and destruction is rife with possibility—of life and post-death—this is what Dakpa conjures with his photography, toying with the extremities of light and dark.

Lending its title to the show, the second body of work Weather Report hosts three installations, each crafting a kind of composite image, hewn by smaller prints made across seasons, climates and time periods. Here, the durational act of observation is both deftly deconstructed and intertwined by Dakpa, making the photograph an awakened site of enquiry. In this edited interview, Dakpa unpacks his process of making, his relationship to the medium of photography and the kinds of mediations it continues to produce for him.

Tenzing Dakpa, Weather Report, installation view from Experimenter–Hindustan Road. (Kolkata, 2024. Images courtesy of Experimenter. Photograph by Vivienne Sarky.)

Annalisa Mansukhani (AM): Manifest is a work that has taken shape over the past few years. You have been living in Goa for a while, so what was it like working with the landscape through a lens that allowed you to study the devastation that you have recorded? What has that relationship been like, and how did it emerge?

Tenzing Dakpa (TD): A practice that I have had since graduate school—and retained after moving to Goa—is going out every day to photograph my immediate environment. As a photographer, I need to point my camera at a subject matter. And in some way or the other, my immediate surroundings have always been the site of my interests, which have to be conveyed through image-making. When I moved to Goa, I would photograph every day for a couple of hours, driving around different neighbourhoods. Coming from my earlier work The Hotel (2020) I have always been interested in this idea of labour—how people inhabit something, how they build a habitat and also how they perform its upkeep. The act of labouring to maintain something is what I feel defines the sense of our lives, keeping with what we live with, what we live for and what we aspire towards. These interests naturally folded into the landscape of Goa, keeping with this subconscious act of continuously photographing. It is not like I have a preconceived idea of what I want to photograph. Instead, I am on the move; I am driving and looking at things that I am drawn towards. In noticing these simple things—people tending to their habitat, to their land—I take my photographs.

With Goa, as compared to other landscapes, what I have noticed is the drastically different vegetation and climate. It is so rich in flora and fauna, and the dense overgrowth requires a lot of upkeep, causing there to be a relationship where people are trying to keep nature at bay. I was photographing for a project titled God’s Gift (2023), and I realised that there were a lot of recurring themes I could identify from earlier works, but also familiarities that were being developed with how I was looking at the landscape. I positioned the work within the context of North Goa particularly, because of the mining industry and the push and pull that occurs around it. People depend a lot on mining and fishing for their livelihoods, but at the same time, there are a number of sanctions being placed on them because of its effects on the environment. Goa is also facing a lot of issues with migration as people move here from other states, especially during the pandemic, all of which is causing a huge spike in real estate. As things are being built everywhere, there is a lot that is happening with the environment. This was the context in which God’s Gift was taking shape, but I eventually hit a wall when it came to making photographs.

In this pause, I began noticing the coverage on the burning of forest and agricultural lands, especially spiking from 2020. There was a lot of speculation that it was man-made, and oddly enough, as a spectator, it was something quite eerily beautiful to look at. I had never seen a hill on fire before, and I did not have any expectations of what I would encounter as I got closer to this occurrence. I began going out at night and photographing these dead, dying forests, and the images that began taking shape were very striking. It opened up a new door for me to think about the cost of development, something that was causing this decimation of natural environment through real estate and “reclamation.” I was interested in what these collisions would produce, and the photographs began to fold a lot of these ideas into themselves. It became a revelation for me to be able to use photography to describe this devastation in a new way, something that could both transcend but also stay rooted in the politics of it all.

Tenzing Dakpa, Weather Report, installation view from Experimenter–Hindustan Road. (Kolkata, 2024. Images courtesy of Experimenter. Photograph by Vivienne Sarky.)

AM: There is a particular emphasis that you place on the image, almost as though it is something that mediates your encounters with your surroundings. What is it that imbues your relationship to the image—and to image-making?

TD: I think it is a sense of being that stems from the realisation that you are elsewhere; this makes photography a way for me to establish contact with the place that I am living in. With photography, there is a whole other kind of language that exists, one that has its own bones and dispenses information in its own way, inviting you in. And that is why I think the medium is interesting to me, because at the end of the day—with a work like Manifest—I made these images, and then I also went ahead and crumpled them. There is a certain amount of abstraction that happens in that gesture, to move the subject a little further from reality, making it more than a record or evidence. This kind of intervention presents the sort of experience I think works for me when it comes to photography, something added to expand how we receive what we see.

AM: With your ongoing exhibition at Experimenter, you mentioned including sound as an additional element in the space. How have other mediums intersected with image-making for you?

TD: I have always been interested in music, and I am a hobbyist musician as well. The idea of sound was not something that I had consciously thought about. It was something that Veerangana Solanki suggested, and it got me thinking about how I already have material I could be thinking with, for this work. I have also worked with feature and fiction films, where I was involved in sound as well. So it gave me an opportunity to insert sound into my work, which to some extent performs what the image cannot. Especially with how Manifest came together—with images made in the dark of the night, using the flash and these forms of illumination—it became important for me to bring the existing environment into the space in a tangible way. In these images, the light recedes into the background, things fade and reappear, but then you are made aware of perhaps a train passing behind the hill, a waterfall in the distance, a bar and music playing somewhere. For the opening of the show, we tried to work further with the contexts of the display, with a set of playlists that tied back into the temperament and tonality of the landscape and also of where I am in terms of my headspace. Sound—or music—adds to the environment, and I wanted to bring that into the gallery space, as one medium in conversation with another.

Manifest XIV (2023. Archival pigment print, 40 x 50 inches, 101.6 x 127 centimetres).

AM: Across both Manifest and Weather Report, there are ways in which you have toyed with scale and structure, both extending and leavening the affect that they produce. With Manifest in particular, there is this gesture that you perform of crumpling the image; with Weather Report, we see these layered compositions arise. I am curious to know more about what led you to think of these gestures—the way they fracture the surface of these images as well as how we view them.

TD: I think it came from my interest in printing, essentially. I print all my images, and I have worked as a printer with a lot of bookmakers. I profile my own paper, and I enjoy using, finding and sourcing papers to work with. That is something I have been doing in my studio in the last couple of years, and it came from that interest. This idea of crumpling was something that I landed on, as an intervention that I wanted to make to the images. The images, just by themselves, look “too photographic.” And I wanted to take the image and do something to it instinctively. I ended up crushing it one day, and it opened up, giving the sort of feeling one gets from the contours of the landscape. I felt it worked in a way that gave these images a very sculptural, three-dimensional quality.

The idea for the Weather Report series and its grid-like composition grew from the limitations I have with printing large formats. My printer only produces smaller sizes, and I was curious to see what would happen if I worked with grids or panels of prints, instead of single images. For Weather Report, working with a medium-format camera, I wanted to try an approach to explore what it might produce for me and for the exhibition. It was interesting to think of the image revealing itself when you install it, when it all comes together. The prints curl, they breathe and they move; adding an element of life to the environment and a moral abstraction to the life of it all.

Tenzing Dakpa, Weather Report, installation view from Experimenter–Hindustan Road. (Kolkata, 2024. Images courtesy of Experimenter. Photograph by Vivienne Sarky.)

AM: As you have moved through different places and landscapes, possibly assimilating different experiences with the medium and its capacities, do you think your relationship to photography and image-making has evolved over time?

TD: I went into the space of identity for a long time, especially when I was starting out. When I started photography, I learned it by doing self-portraits in New Delhi. I would take pictures of myself and my then-girlfriend. I was in a relationship for about six or seven years and made these images of my partner in New Delhi. She was from Nagaland. This was about photographing ourselves in the city and seeing what that looked like. Being in Delhi and from the Northeast, you tend to feel cushioned by certain spaces and then also cornered in environments where you feel alone or unwelcome. This idea of inserting ourselves within different parts of Delhi and photographing that was a way of marking ourselves in a landscape that seemed foreign.

I also explored the idea of being a Tibetan in a diaspora and Tibetan identity within mainstream mainland India. I went to Dharamshala and photographed some of the young Tibetan students living there. Many of them come to Delhi for higher education, only to experience cultural shock and racial typecasting. They often feel like they do not belong. I made portraits of the students, printed them, and installed them in public places where people would walk over the images, causing them to disappear. This symbolised the need to survive in a city and how it can erase your identity, roots, or history. This I could relate to, coming from a Tibetan family in the diaspora, moving to Delhi, and then New York, where there is a constant shift away from home. As a second-generation Tibetan in exile, home is always elsewhere. So the limitations of identity became a bit disempowering because I kept looking back at the past as a way of reading or finding meaning in my images. I did not want this fixation to persist because it did not open up the possibility of new images for me. This has been a major shift for me in my relationship with photography because I seem to be gravitating more towards photography as an exploratory process. I am enjoying seeing where it takes me, rather than telling a fixed story or narrative based on memory.

Manifest XXV (2023. Archival pigment print, 40 x 50 inches, 101.6 x 127 centimetres).

To learn more about Tenzing Dakpa’s work, read Ketaki Varma’s two-part interview with the artist on his series The Hotel (2020).

All images are from the exhibition Weather Report (2024) by Tenzing Dakpa, on display at Experimenter Gallery, Hindustan Road, Kolkata. Images courtesy of the artist and Experimenter, unless stated otherwise.