Consolidating Political Cultures: Majoritarianism in the Agrarian North

Defence Garden, Shamli, a real estate enterprise in Uttar Pradesh promises to offer an island of peaceful living with all modern accessories to its occupants.

The rapid expansion of the national capital of Delhi portends to engulf and reconstitute the character of the hinterlands located in neighbouring Haryana and Uttar Pradesh. Towns such as Shamli, Muzaffarnagar and Baghpat in western Uttar Pradesh that were considered to be a part of the agrarian sugarcane (ganna) belt are today exposed to a frantic pace of urbanisation. Residents here find themselves surrounded by a labyrinth of billboards and handouts that advertise the must-haves for an imagined cityscape. Real estate projects, vehicle showrooms and ‘international’ schools queue up as symbols of aspiration along the highways. This is despite the prevalence of severe debt stress, rising inflation and atrophied towns faced with crumbling infrastructure.

Action Aid flier announcing a workshop to disseminate information on behalf of government schemes provided by the Ministry of Labour and Welfare in Uttar Pradesh. (Source: Author’s personal archives)

The glossy veneer of development is endorsed by the increasing role of local vigilante groups. In the past decade, these groups have emerged to take the place of local NGOs and civil society activists, which now merely repeat government promises by uncritically accepting policy as rights. In the image above, Action Aid India, a multilateral not-for-profit organisation, has been reduced to disseminating information on behalf of government schemes. This is a marked departure from the way such organisations previously used their resources to build capacity and train/equip the working poor with employable skills. With the space for grassroots activism ceded to an army of freshly minted social workers of the far-right, these emerging groups actively advocate populist claims of the government, while simultaneously carving out possibilities of mobility within the socio-political landscape of rural towns in the north of the country.

Online poster carrying images of figures of the Hindu pantheon and national icons issued by the Akhil Bharatiya Veer Gurjar Mahasabha (All India Brave Gurjar Organisation) welcoming its new members. (Source: Whatsapp)

These manoeuvres are occurring in the wake of an affirmative response to the shift in sensibilities toward the far-right, where important issues such as joblessness and crises in social reproduction are being sacrificed for an endorsement of caste pride and solidarity. Thus, the Akhil Bharatiya Veer Gurjar Mahasabha in Rajasthan is deploying a variety of images that represent caste and religious deities along with national icons to forcefully foreground its “All India” credentials. Such solidarities are not just performative but actively serve to stitch together alliances of caste outfits under a common majoritarian commitment to violence. However, this has not helped to avert the crisis of forced bachelorhood as marriage prospects remain hinged on expectations of the tenured sarkari (government) job.

Poster issued by the National Jat Tejveer Sena announcing a Jat mass marriage ceremony to be held on 5 May 2023 in Ujjain, Madhya Pradesh. (Source: Author’s personal archives)

In the images above, the invitation—an announcement of a mass marriage being organised under the aegis of the National Jat Tejveer Sena (grand army of Jat warriors) by members of the Jat caste in Ujjain, Madhya Pradesh—encourages families to register and participate. In a highly competitive marriage market, a definite fear of forced bachelorhood is making these cohesive caste groups come up with ways to arrest the despondency being faced due to a decline in marriage prospects.

Image showing members of the Kushwaha caste announcing the pride march to honour the birth of the deities Lav and Kush. (Source: Whatsapp)

Similar events are carried out across the agrarian north. Take, for instance, the above image, where members of the Kushwahas are planning a Shobha yatra, or a show of pride, in the name of the mythical figures Luv and Kush, believed to be the sons of the Hindu deities Ram and Sita. The Kushwahas in Madhya Pradesh are classified as an Other Backward Class in several north Indian states, and for years now they have alternated between a claim to marginality and invocations of caste and martial origins.

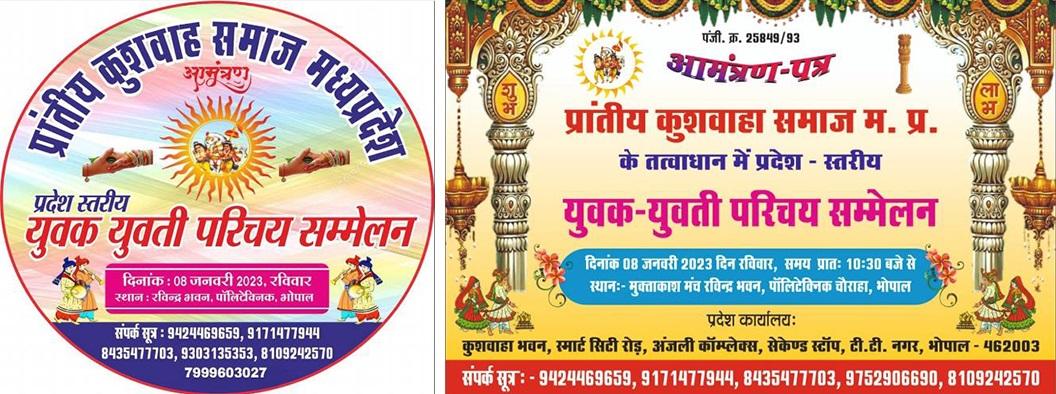

Image issued by the regional Kushwaha caste of Madhya Pradesh announcing a meet up for prospective brides and grooms of the community. (Source: Whatsapp)

These yatras and other such events work as consolidated caste gatherings where the samaj (community) calls upon eligible boys and girls from the community to participate in a Parichay Samelan (meet and greet festival).There is a clear urgency to invoke history in order to assert identity within public spaces or maintain caste through alliances of marriage. These can be read as responses to a transitory world where the severe stress caused by the crisis in social reproduction is being set aside to gatekeep ‘tradition’. The defence of caste and invented truths culminate in broader majoritarian anxieties that serve to stymie murmurs of dissent that emerge from an atrophied political economy.

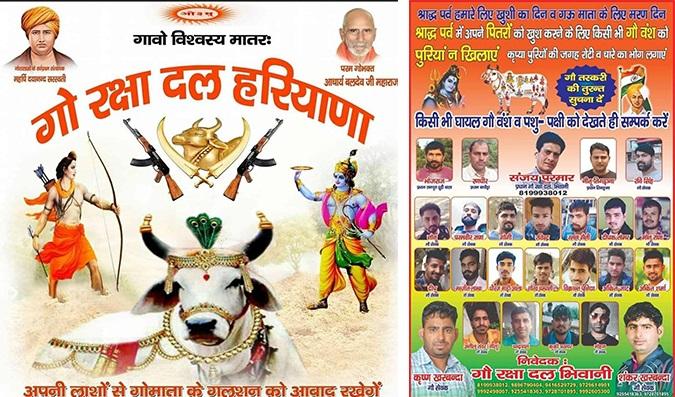

Images issued by the Gau Raksha Dal-Bhiwani, Haryana (cow protectors) asking all gau bhakts (cow lovers) to feed cows in the name of honouring ancestors. (Source: Whatsapp)

In the above image, there is a clear call to militarise in the name of the cow in the state of Haryana. It represents popular deities of the Hindu pantheon who stand watch over a cow, symbolically protected by modern day assault rifles. The anonymous faces that mark the jobless youth in India have now assumed a far right socio-political character as the nation’s youth have become an informal ally to the disruptive developmentalist experiments occurring in what was once the agrarian hinterland.

To learn more about new media images, read Anisha Baid’s two-part essay reflecting on the digital image in the context of questions of authenticity and authorship. To learn more about the majoritarian government-endorsed cow vigilantism, read Najrin Islam’s review of Natesh Hegde’s Pedro (2021).