Cartographies of Control: Mapping Coastal Regulation Zones

The creation and dissemination of maps are inherently political acts, reflecting ideological underpinnings of prevailing power structures. Historically, cartographic exercises have been used as mechanisms of control, shaping territorial claims, resource allocation and social order.

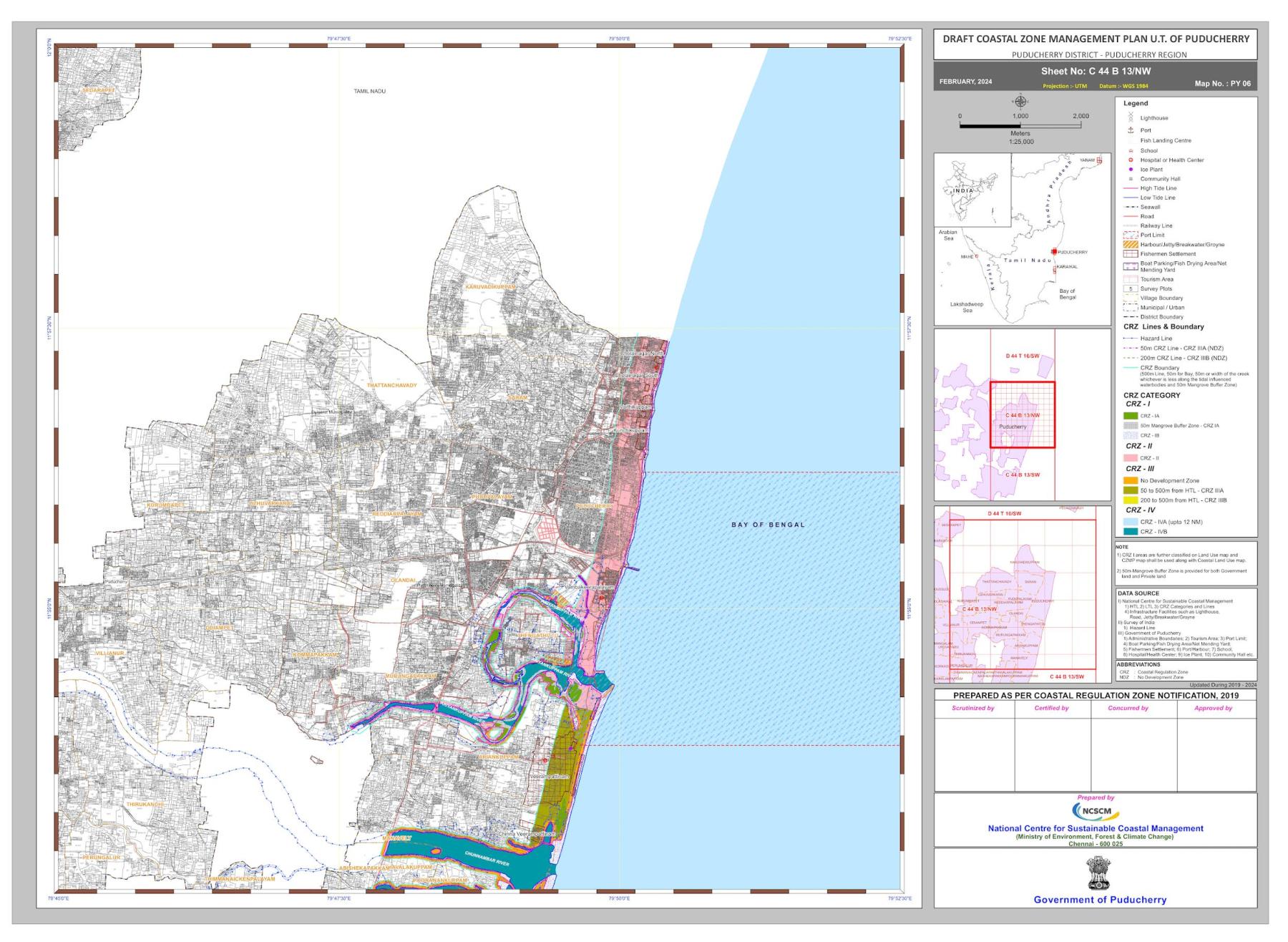

Revised Draft (February 2024) of Puducherry’s CZMP. (Image courtesy of the Puducherry Coastal Zone Management Authority)

The 1:25,000 map of the Coastal Zone Management Plans (CZMP) partitions the coastline and provides a detailed demarcation of coastal boundaries, including those of individual villages, the port limits and ecologically sensitive areas such as mangroves. Notably, the map also indicates the high tide line (HTL) and low tide line (LTL), which are crucial for determining the extent of the coastal zone.

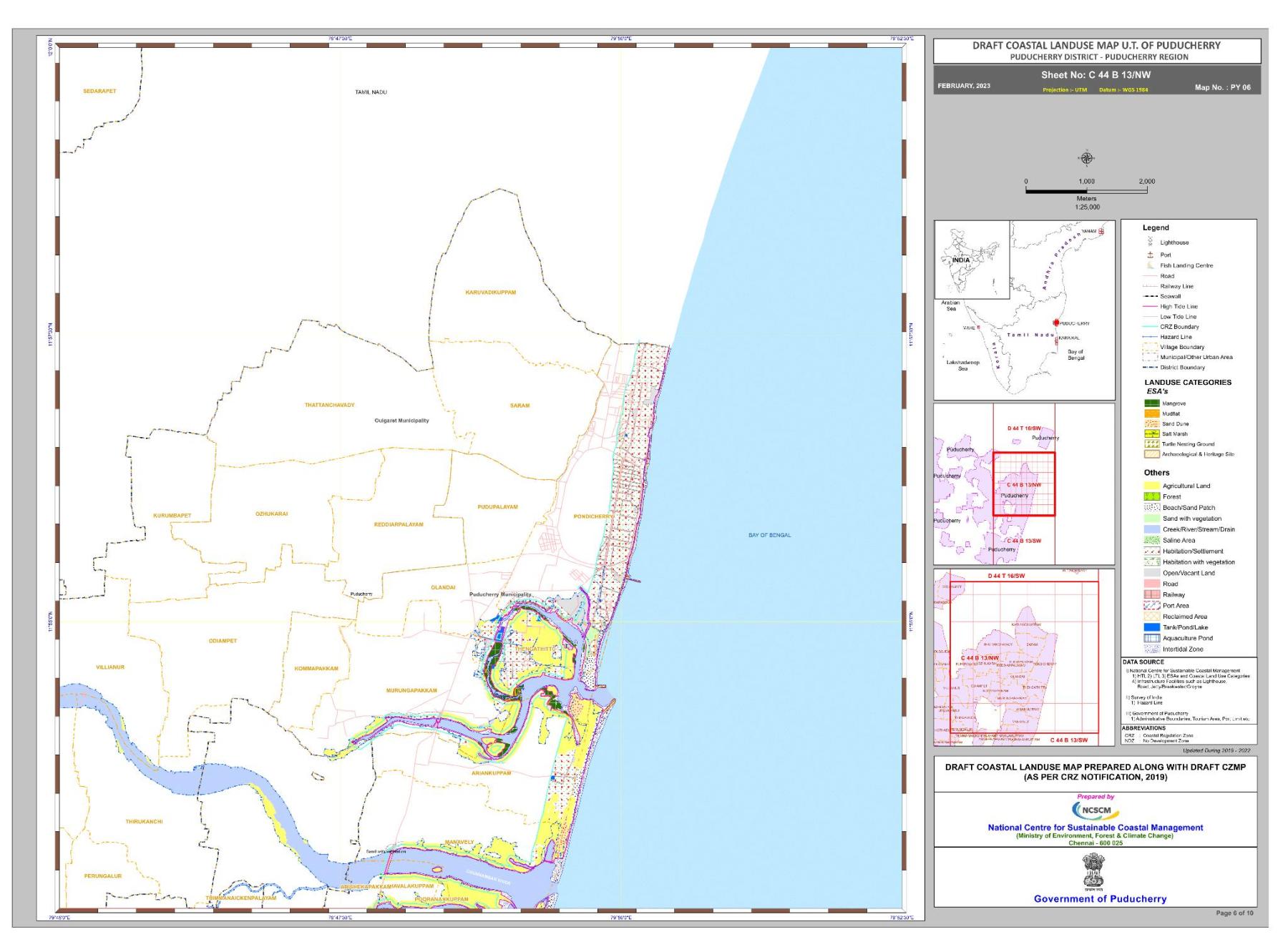

Draft Coastal Land Use Map Prepared along with Draft CZMP. (As per CRZ Notification, 2019)

By marking permissible and restricted zones, the HTL and LTL influence land use restrictions and development activities. While ostensibly aimed at environmental protection, this process of spatial planning determines access to resources and often results in disproportionately adverse impacts on the livelihoods of coastal communities.

Chinna Kalapet fisherwomen dry fish in the only space between the village seawall, which was built to control coastal erosion. (Image courtesy of Nithya K.)

The spatial dynamics of the coast, referring to the interplay of natural processes like erosion, sedimentation and storm surges, as well as human activities like development and resource extraction, directly impact the opportunities available to coastal residents. For instance, construction and development in ecologically sensitive areas, such as mangroves or coral reefs, can promote the growth of tourism-related businesses which rely on pristine coastal environments.

Fisherman mending crab nets for the next day’s catch. (Image courtesy of Nithya K.)

This can lead to regulations on traditional fishing methods and practices, including catch quotas or fishing gear, which may limit the amount of fish caught, reduce the value of catches or even force fishermen to switch to less profitable activities. This affects the income of coastal communities as they are heavily reliant on the sea, disrupting the delicate balance between human activities and the marine ecosystem.

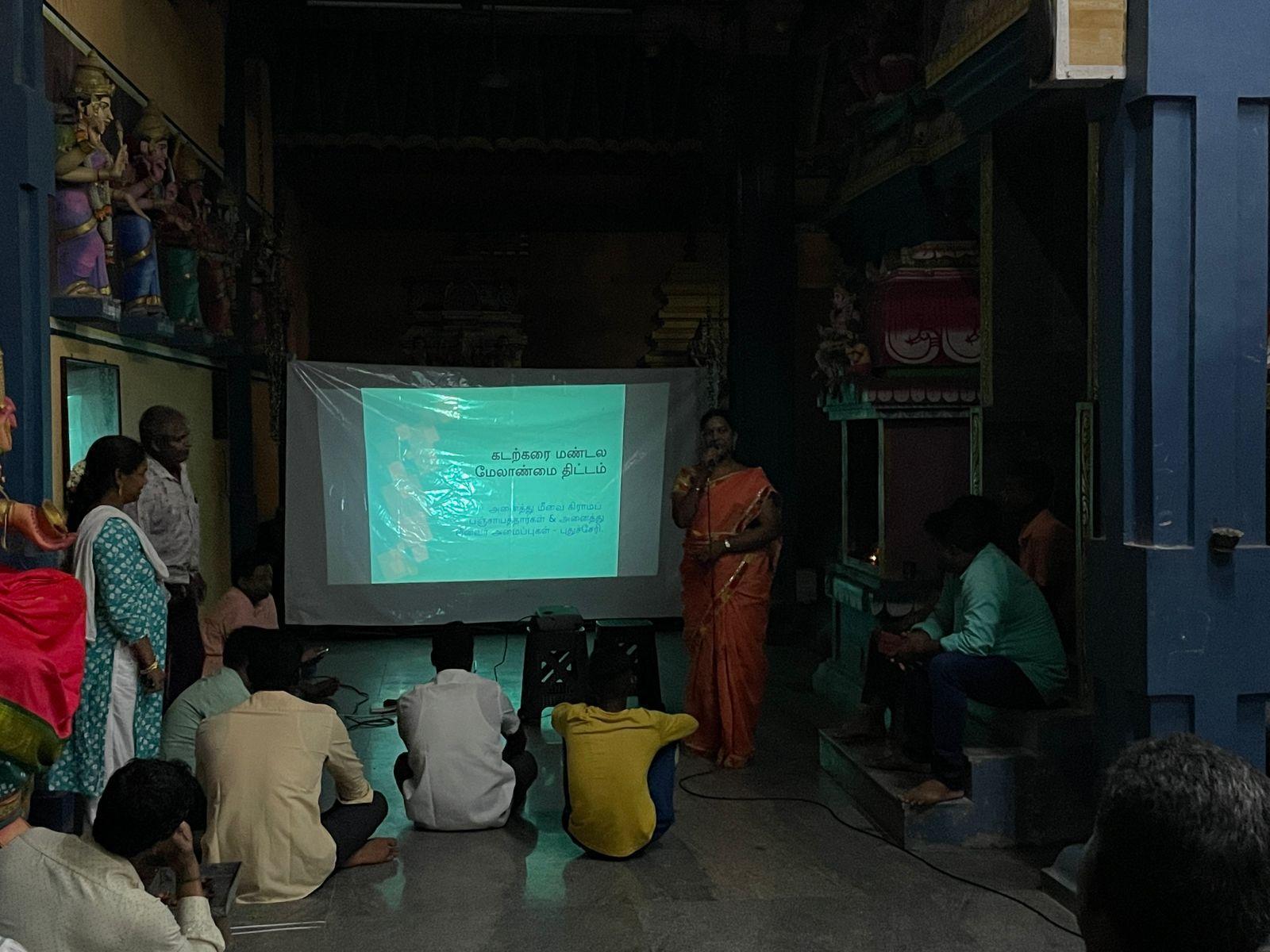

The meeting in Solai Nagar South is moved indoors, in the Sengazhuneer Amman Temple, due to relentless rains.

In response to these challenges, coastal communities and local activist groups have often engaged in legal battles and public protests to contest the cartographic representations of their territories. They have utilised public hearings mandated by CRZ notifications of 2019 as platforms to voice their concerns, challenge the scientific basis of zoning decisions and demand greater participation in the decision-making process. These efforts have led to revised CZMPs, demonstrating the power of grassroots activism in shaping coastal governance.

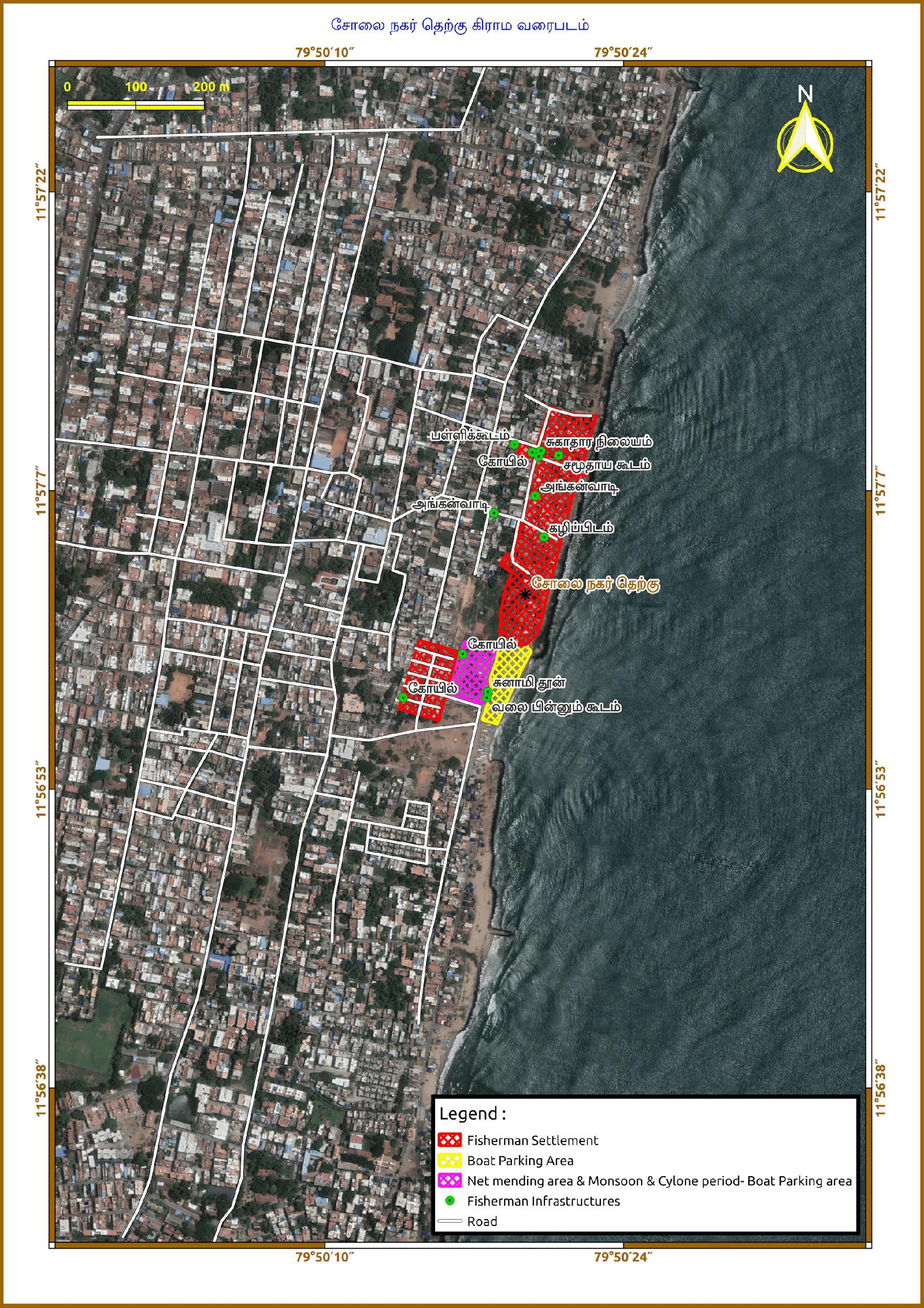

Community-driven map of Solai Nagar South, Puducherry by the collective, ROSA. (Image courtesy of ROSA)

These community-driven maps often go beyond the boundaries of villages, marking settlements, boat parking areas and other public infrastructure such as anganwadis, temples, public toilets and net mending areas. By creating their own representations of the coastal landscape, communities can challenge official maps, highlighting areas that may have been overlooked or misrepresented. This empowers local residents to participate more meaningfully in decision-making processes and advocate for their interests.

The Health and Wellness Centre in Solai Nagar South—the site of a meeting to discuss the community mapping—is absent on the 1:25,000 scaled CZMP published for public consultation but is marked in the ROSA Map.

For example, in Solai Nagar, the Health and Wellness Centre was not included in the CRZ maps. It was instead mapped by the collective ROSA, which has been involved in community mapping of the coastal zones. This discrepancy demonstrates that CRZ maps do not always accurately capture the nuances of local land use and infrastructure, and highlights the importance for community-centric planning for comprehensive and updated mapping to ensure that local needs are adequately addressed.

In the Tsunami Quarters in Solai Nagar South, Puducherry, the families spill out of their tenements, leading them to build more huts near the Quarters. However, this informal settlement remains yet to be mapped.

Similarly, the Tsunami Quarters in Solai Nagar, Puducherry, was just categorised as a "Fisherman Settlement"—where fishing communities live—even though the community also has fish drying areas, net mending areas and a small place of worship that they have built and maintained. Despite facing displacement and loss, the community has managed to rebuild and maintain their cultural identity and various community facilities, demonstrating their commitment to sustainable practices. It is crucial for CZMP to recognise such land use and provide targeted intervention.

The net mending areas on the coast right outside the Tsunami Quarters in Solai Nagar South.

The case of Solai Nagar thus demonstrates the complex interplay between cartography, governance and the human experience in coastal areas. Far from being neutral representations of territory, CRZ maps have emerged as potent instruments of state power, shaping livelihoods, access to resources and the overall well-being of coastal residents.

Fishermen in Bommayarpalayam prepare their ring seine nets at the end of the fish lean season. (Image courtesy of Nithya K.)

To learn more about India’s various coastal ecologies, revisit Gulmehar Dhillon’s curated album of M. Palani Kumar’s work with the seaweed farmers of Tamil Nadu, Sukanya Deb’s conversation with Paribartana Mohanty and Ketaki Varma’s reflections on Sohrab Hura’s practice.

Images courtesy of author (taken in 2024) unless mentioned otherwise.