Visions of the Apocalypse: Ecological Disaster through Social Media and Myth

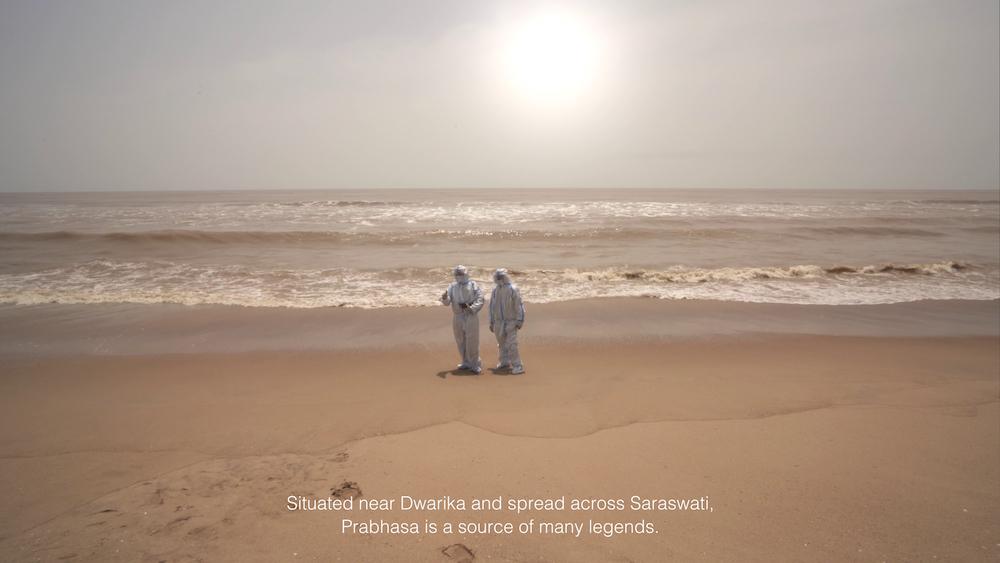

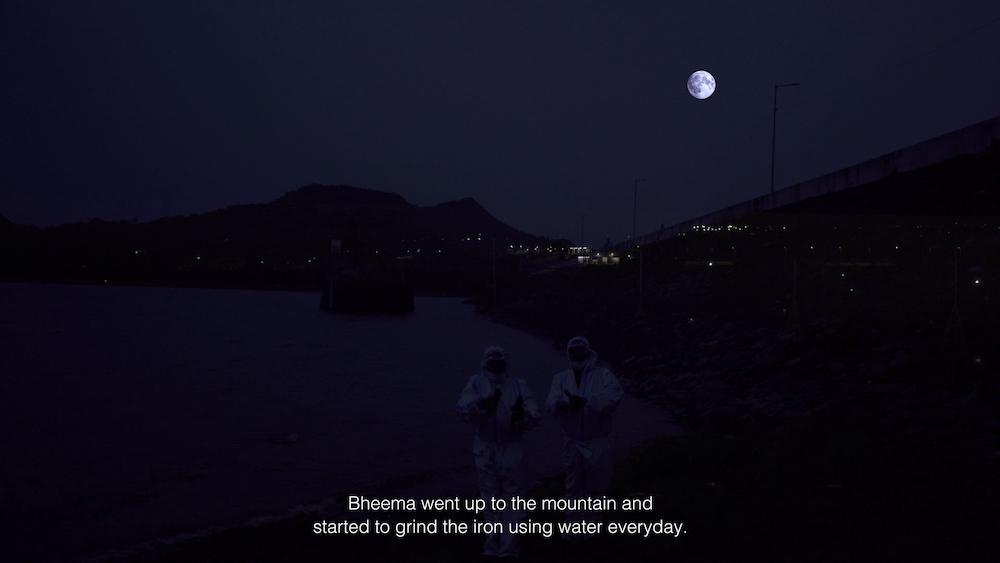

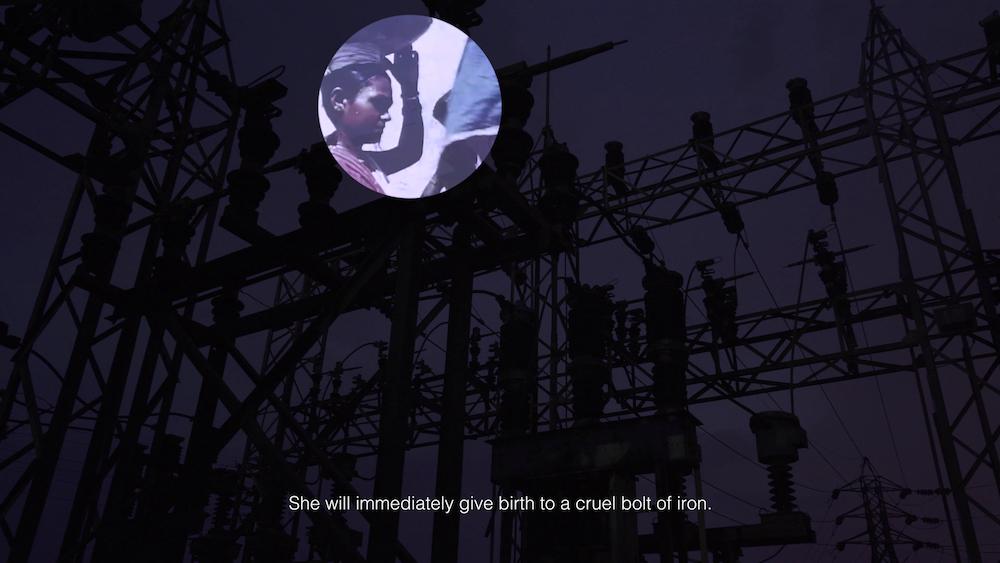

Paribartana Mohanty’s video work Four Songs of Apocalypse (2021) uses mythology and folk traditions to look at narratives of disaster. Set against the ongoing ecological collapse of the coasts of Odisha that has led to rising waters and eroded land, mythological prophecies become a confluence point for Mohanty’s work. Dasakathia—a traditional Odia folk performance form by travelling artists—is performed as a telling of stories from folklore, where disasters are envisioned in the form of the oceans being poisoned. The performers wear Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) kits, which have become commonplace since the Covid-19 pandemic started. The dress gestures to an apocalyptic foretelling, where prophetic visions are self-fulfilling; the climate crisis is being predicted on a constant basis, yet we continue to live through it and fulfill the very same. The apocalypse takes different forms—such as earthquakes, flooding, cyclones, depletion of resources and so on—and Mohanty uses mythological underpinnings to draw parallels between contamination, purity and ecological disaster.

Sukanya Deb (SD): Could you elaborate on your research process and the focal points, including where the idea originated from?

Paribartana Mohanty (PM): While I am from Odisha, I have lived in Delhi for the last fifteen years. So, whatever happens environmentally or on a societal scale in Odisha, I only get the reflection of as I am not directly seeing or experiencing it myself. Since 1999, there has been a cyclone in Odisha every year. Whenever it happens, I hear stories from my family members about it, which offered one way to view such an environmental disaster. Another way is through social media, where you are bombarded with images. In seeing disaster manifest layer by layer through social media, there is a creation of a kind of premature apocalypse that you experience only through the information or through whatever remains. Gradually this information is diluted. And because of the algorithms in place, certain kinds of images circulate more, while certain other images do not circulate at all. So, this is how I started thinking about environmental crises—from the idea of how technology mediates and manifests these crises. I looked at mythological texts as well, simultaneously realising the issues with the dated nature of these texts that are often found blaming women or aspiring towards a certain purity, etc.

SD: Social media mediates the way a story is told, through multiple voices. Spectatorship runs parallel to the treatment of mythology. It is interesting how you use that quality of storytelling to show people’s reactions to moments of crises. I am curious as to how you came to the idea of mythology being told through a contemporary lens, since the folk singers are wearing PPE suits, signalling a post-COVID time, where ecological disaster seems much more pervasive. Could you speak a little to that?

PM: Mythology has always shaped my way of thinking. While I was growing up in Odisha, I was told a lot of ghost stories and mythological stories by my father, grandparents and other relatives. Today, I tell stories during lecture performances, where I keep these references because what fascinates me about mythology is that there are always multiple ways of telling a story.

With regards to the dress and costume in the film, the dance or performance form that you see is Dasakathia. It is a folk tradition, not a classical one, so there is room for play and there are no rigid rules or regulations. So they are able to change their costumes, unlike a traditional Odissi dancer, for example, who would never wear this because they are restricted by the costume and grammar of it all. If you listen to the Dasakathia song closely, you will notice that there is a kind of dialogue, a message that the singer is trying to transmit. The performers travelled to villages and sang and told stories of God’s glory, that was how it used to be. But it is also very contemporary, bringing in references from mythology while dealing with current issues, things happening in present time, complexity of society, marriage issues, etc. Besides gesturing towards Covid-19, the PPE kit brings the apocalyptic sense to the visual.

Four Songs of Apocalypse is available to view online till 6 February 2022 as part of the Chennai Photo Biennale.

To read more about the third edition of the Chennai Photo Biennale, please click here, here, here and here.

All images from Four Songs of Apocalypse by Paribartana Mohanty. 2021. Images courtesy of the artist and Chennai Photo Biennale.