Smoke and Fire in Nocturne: Ahmed Rasel’s Investigation of Bangladesh’s Brickfields

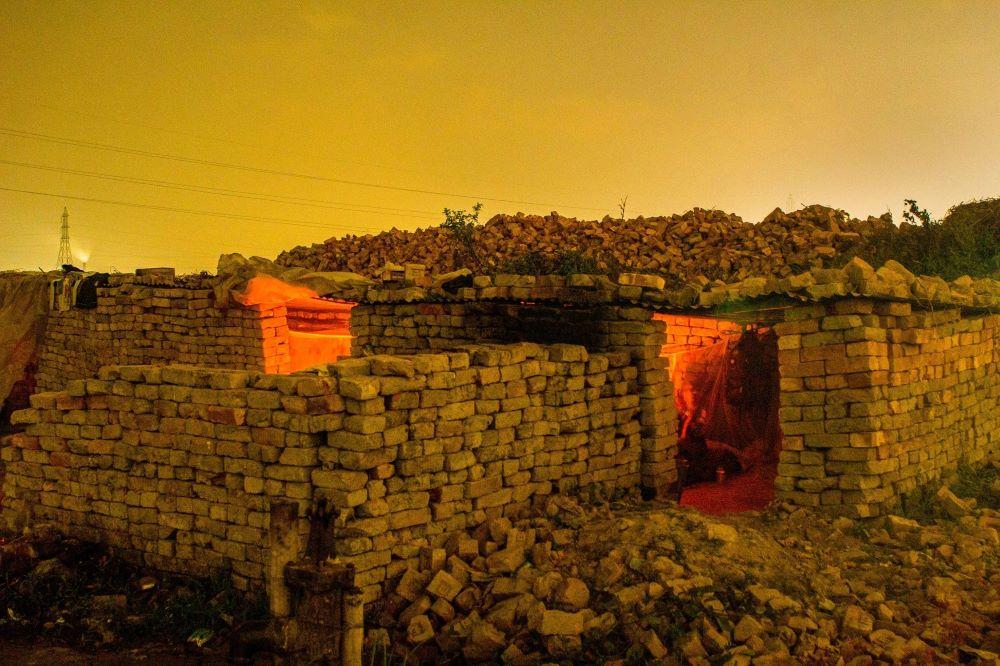

Featured by the Chennai Photo Biennale’s Maps of Disquiet edition (2021–22), Ahmed Rasel’s project Nocturne presents a set of evolving perspectives on the complex, messy history of brick kilns in Bangladesh. These can be seen everywhere in the increasingly urbanising landscapes of the country, growing denser in presence around the edges of cities like Dhaka. They also contribute overwhelmingly towards making Dhaka’s air pollution the “worst in the world” in terms of suspended particulate matter. In Rasel’s patient, long-exposed photographs where nocturnal shades assume an almost pastel-like intensity, the kilns acquire an identity that is richer than that of the simple antagonist depicted in journalistic accounts of environmental damage. They become, instead, dark, looming anti-heroes in charge of their own narratives over the various dystopic landscapes. As fly-by-night economies establish themselves around their presence, homes are wrested out of the bleak spaces for temporary shelter, with brick piles suggesting a crude, parodic fantasy of permanent habitation that is denied to the thousands of labouring families living on these desolate lands. The kilns smoke broodingly over the landscape, as if contemplating their own implication in the decay. A unique craft-making tradition, brickmaking struggles to adapt to safer methods of manufacture in a beleaguered environment, subjected to the stresses of accelerating capitalism.

Rasel spoke to Ankan Kazi about his growing interest in the activity of brick-manufacturing, his own nostalgia for brickfields—that is now irreversibly damaged—and the intricate dance around brickmaking’s ambivalent position in legal parlance that merely perpetuates the oversights that keep them fuming hazardously around some of the most densely populated regions in the world.

Ankan Kazi (AK): It was surprising to find out that brickmaking is not recognised as a formal industry in Bangladesh, even though legislation seeking to control their polluting technologies was passed as early as 2013. What are the main problems that prevent a smooth transition to cleaner methods and what visual codes do you think might help complicate the story of their presence that has been missing in journalistic accounts so far?

Ahmed Rasel (AR): Nocturne is an architectural documentation of brickfields and their surroundings in Bangladesh. The photography project depicts how the brick industry of Bangladesh prolongs the destructive impact on the environment. Dhaka ranks worst in the air quality index in the world. The local newspaper Daily Star reported, ‘‘Brick kilns were identified as the single largest source of air pollution in Dhaka city, with fifty per cent of the total pollution coming from them." Environmentalists claim around 5000 are located in and around Dhaka.

So, my photo essay carries the above information, but at the same time, it goes beyond this to make it aesthetically strong. I have experimented with long exposure techniques in the evening light to make a difference in the process. The timing also helps me to get access to the field. In most cases, the owner and the manager do not want to allow the photographers to talk with workers or shoot in the field. After sunset, the situation becomes slightly more photographer-friendly (in my personal experience) and the workers become relaxed, as most of them do not work at night.

Many local and international journalists have also shot in the brickfields as part of their assignments in Bangladesh, but they just include one or two photographs to refer to the overall situation. Those who focused on the environmental pollution by brickfields did not work for a long time to articulate the issue properly. That is why I decided to follow this as a long-term project and created a certain kind of visual style to catch the people's attention on a story that is otherwise known. I am not telling a new story here. Local media and authorities are very much aware of the situation. So, I had to tell the story in a manner that creates a new sensitivity.

This is an ongoing project. However, because of the pandemic, I was unable to shoot in the field for two years. It is a self-funded project and I have been working on the issue for more than six years now. So, sometimes, I have to wait for a pleasant situation to visit the field. Also, brickmaking is a seasonal business. Most of the kilns only run their activities for four-to-six-months a year. Because of those obstacles, I missed many events which were important. Before the pandemic, I started shooting in the countryside, especially in the hilly region, to understand the issue from different perspective. In the coming seasons, I would like to create more in-depth and journalistically communicative visuals to discuss the issue more profoundly. For example, I started, taking videos in the field and studying Google maps to address the issue in a communicative way. I would like to start a portrait series of the workers from the current brickmaking season to highlight another viewpoint of the story—from the workers' perspective.

AK: You show the presence of the chimneys to be near-ubiquitous on the horizon, but also as a structure that constructs its own complex economy around its presence—with migrant workers’ makeshift homes, children playing in the brickfields, the generation of enormous quantities of waste, etc. These complicate the question of doing away with the brick kilns totally as they provide shelter and occupation to thousands of families every season, even as it plunges them into hazardous work. Do you think a complicated picture of the brick kiln economy might ultimately harm efforts to simply eradicate them? Is that even a desirable action, at this point?

AR: The brickmaking industry awakens a complex situation in Bangladesh. With the rapid urbanisation rate, Bangladesh needs billions of bricks annually to fulfill the demand. As “concretised culture” spreads rapidly through the country, bricks have become one of the most consumed commodities even in the village areas, which have been almost entirely dependent on nature-based materials for their houses for centuries. Apart from mega infrastructure like highways, flyovers, metro rail, big bridges, hundreds and thousands of local roads and culverts have been built across the country in the last two decades. Even remote earthen roads and wooden bridges are converting to concrete structures rapidly. Bricks are the key element of this expansion.

Converting an old technology-based brickfield into a modern kiln demands a one-time big investment for the owners. In their recent procession against the mobile court operation to prevent illegal operation of brickfields in different parts of the county, the Brickfield Owners’ Association said that the local banks or the government authorities are not initiating enough loans for them. So, they are facing an enormous problem to convert their kilns to modern ones.

With green groups and organisations, the Bangladesh government has been rightly advocating for alternatives to conventional kiln-fired bricks. The Housing and Building Research Institute (HBRI) advocates for four or five types of bricks. They are proposing Compressed Stabilised Earth Block, Interlocking Block, Thermal Block, and Concrete Hollow Block. Some are already in production, in the areas of Dinajpur district, Narsingdi District and Thakurgaon District in Bangladesh. But the irony here is that all these “environment friendly” bricks are not necessarily “green.”

Since then, it was announced that state-run agencies would use “eco-friendly” bricks for their public construction. The Environment, Forest, and Climate Change Ministry had issued a notice in 2019 targeting ten per cent usage of “eco-friendly” bricks by the 2019–20 fiscal year. The plan was to increase by hundred per cent by the year 2024–25. But things are not going according to the plan. According to the Bangladesh Concrete Block Association, only 13 per cent of the target could be achieved to date.

But the change in law has become a kind of calamity from the riverine perspective. According to the latest revisions in the law, permission is needed only from the District Commissioner (DC) to extract soil from riverbeds or wetlands to make bricks. The amendment has made mining sands for the brick kiln from rivers very easy. Sand mining from rivers has been permitted by a previous act, “Sand Quarry and Soil Management Bill 2010” in Bangladesh. According that act, district administrations can lease out portions of a river for sand mining.

Sands from rivers are already being extracted for “eco-friendly” brick kilns, which are already in production. Many major rivers of Bangladesh are now under erosion, biodiversity losses, and pollution because of haphazard sand mining. Large-scale river dredging for “eco-friendly” bricks will definitely worsen the situation. So, there is a severe lack of coordination among the authorities responsible for taking care of the whole issue.

On the other hand, as you mentioned, thousands of families depend on the brickmaking industry for earning their living. Also, millions of people are directly affected by the pollution related to the brickmaking process, especially in the urban areas where coal is the primary source of burning brick. There is hardly any easy way out for the time being. Only the higher authorities can initiate a plan which will accommodate all the problems and the possibilities. According to most experts, the government needs to reduce the level of environmental damage by making eco-friendly bricks through proper monitoring and coordination among all departments. That is the solution now. At the same time, it is necessary to ensure a good salary and working environment for the workers.

AK: Brickmaking has a long and storied tradition as a popular manufacturing art in Bangladesh, due to its unique deltaic clay and alluvial soil—making the whole enterprise heavily dependent on the landscape’s existing ecological health. Your work shows how stark its decline has been into an urban wasteland, instead. Did you start with a didactic approach, hoping only to prove their baneful effects on the environment, or did your understanding of their symbolic presence change over time, requiring a different approach to photograph them?

AR: I will share the context of how I started the project years ago...

There was a brickfield near my village home. When I was a small child, it fascinated me. Particularly, when I found workers making bricks from clay in a magical way. It created a different impact on me, especially when the chimneys puffed grey smoke into the air. As kids, we used to play hide-and-seek in the abandoned brickfield. Many years later, when I started watching and shooting brickfields which were far away from my native home, I started feeling sad to see the consequences of the brickfields. The consequences have taken away my childhood’s sweet memories.

I had taken a research trip for a class project to Satkhira (a South-Western district of Bangladesh, near the Sundarbans and the India–Bangladesh border). In the late evening, while lying on a dark roof in a shrimp nursery, I suddenly saw smoke in the sky through the leaves of a tree. When I looked carefully, I found that chimneys were emitting grey smoke. I was shocked and disturbed. In that moment, I decided something had to be done with my camera. So I started the project out of curiosity. After a gap, I started doing research more seriously. Then I started taking photographs again in 2017.

Because of those memories, my language remains poetic even though I am telling a serious story. I am aware of the storied brickmaking tradition in the region. In a way, the process is fascinating as it carries the local manufacturing heritage of craft-making which we should celebrate. Documenting the old tradition of brick-manufacturing art could be another interesting story. If we consider the architectural heritage of the region, red brick played an important role. But at the same time, saving the environment is extremely important for me. As a country we have many problems to discuss and environmental pollution is one of them. As I mentioned earlier, I primarily wanted to tell people about the destructive impact on the environment. At the same time, I developed a different visual language which helped me to tell the story. I wanted to create a new visual sensitivity. In a way, my photographs are an example of architectural documentation of the brickfields of Bangladesh which carry the old tradition of popular manufacturing art in Bangladesh.

Nocturne is available to view online till 6 February 2022 as part of the Chennai Photo Biennale.

To read more about the third edition of the Chennai Photo Biennale, please click here, here, here and here.

All images from the series Nocturne by Ahmed Rasel. Images courtesy of the artist and the Chennai Photo Biennale.