Perishable Empires: Re-Historicising the World in Mohini Chandra’s Paradise Lost

Mohini Chandra’s work Paradise Lost—featuring texts, images and performance videos—is currently on display as part of the ongoing edition of the Chennai Photo Biennale (2021-22). The artist develops on her earlier works, in which she retraced patterns of colonial migration that included the movements of her family as indentured labour from India to Fiji. Paradise Lost focuses on the shipwreck as a rich historical event of rupture, which reveals the bare life of risky trade and immigration as bulwarks of the imperial economy that we have inherited today. Salvaging tarnished objects and vintage photographs that were drowned with ships off the coast of the Plymouth Sound, Chandra intervenes critically into debates about reparation. The work suggests restoration, reconfiguration and, indeed, a rewriting of colonial histories as relevant for more equal futures to come. Perhaps most strikingly, her collaboration with the singer and archivist Moushumi Bhowmik, sets off a melancholic note with her video of the latter’s siren-like song about the haunted sea creeping under our skins. It appears to lure the innocent viewer into confronting the dangers of such a difficult past that refuses to remain buried.

Chandra spoke to Ankan Kazi about some of the early inspirations for her work, the implications of the colonial economy for our modern one, and the decentring work she hopes to achieve for historical narratives of the colony and the metropole—a relationship that was based more on mutual assistance and networked allegiances than any unilateral performance of domination or exploitation.

Ankan Kazi (AK): There are plenty of striking conjunctions offered through your work Paradise Lost—where the sea becomes an archive for a potential history of migrancy, while it also threatens the stability of colonial trade and economy with frequent disasters, plunders and shipwrecks. The photograph from the Plymouth auction presents a placid, colonial-style picturesque view of an Indian riverbank, but also bears the inscription that testifies to a massacre that took place there (during the revolt of 1857). How did you come to make these stark pairings that underline colonial history’s offer—of both opportunity and risk—into a narrative of migrancy and survival?

Mohini Chandra (MC): My grandmother's sister was an elderly woman when I met her. It was in a house by the beach in Fiji. I seem to remember large windows letting the sea breeze in. My early research on memory has become memory itself, flawed and partial. She was small, frail, very pale and dressed in white—an ethereal figure. After a long semi-translated conversation, she started to tire. I asked her, finally, where in India her family/my grandmother had come from—the question I had been longing to ask. She whispered, “Kanpur.” This place assumed a dreamlike quality in my mind. Was it the lost home I had been looking for?

Many years later, a good friend found a photograph, in a vintage auction in Plymouth, of a calm riverside scene with a glimpse of ruined classical Indian architecture and a Banyan tree. On the surface of this image, I made out the faint trace of etched script “The scene of the final massacre, ‘Cawnpore.’” I realised it was the same place—my possible ancestral home and a former British military station. I wondered how this apparently idyllic image—of what was, in fact, a record of colonial India's traumatic history—ended up in Plymouth. The links between my family history and this location, connected by wider narratives of empire, seemed to be revealing themselves to me in little fragments as I began work on Paradise Lost.

AK: Your collaboration with Moushumi Bhowmik, the singer and archivist of sound and music recordings from Bengal, is also a significant one. Her work with the Travelling Archive emphasises the migrancy and the crossings inherent in musical traditions that unfold over historical time as well. Are you looking to locate these characteristics of travelling or crossing-over as essential parts of your aesthetic method? What drew you to work with her?

MC: I met Moushumi in Kolkata, while I was in India for an artist’s residency. We had a mutual friend in the UK. We talked, then, about the crossovers in our work and the idea of working together. A few years later, we were able to achieve this in Paradise Lost and another moving image work, Belated.

The use of music as an interpretive, emotive and provocative element in my work has also become important. It allows me to consider other ways of thinking about a space or place and takes us beyond that environment. In the moving image work for Paradise Lost, Moushumi Bhowmik sings a “lament” for lost souls in Bengali. It was very important to me to acknowledge this sense of loss, which cuts across cultures. She is from Kolkata—the port from which my ancestors were transported under colonial rule. While suggesting the links between Plymouth and the rest of the world, Moushumi’s song also brings the gift of recognition, sorrow and empathy to a wider global audience.

Telling the story of “things,” potentially tells us the story of people in a more complex and diverse way. It helps us to see the patterns of movement, trade, travel and exploitation. The story of production and consumption also raises questions about ecology and the way we have treated the planet. These are all possible interpretations of the song “Ei Dubonto Shomoy” or “In these Drowning Times,” composed and performed by Moushumi, especially for Paradise Lost. For me, contemporary art—in its most globally conscious incarnations—has been about releasing untold narratives and asking questions that may not have been asked before. It is quite “decentring” to have questions asked in new ways. Contemporary globalised art practice has also been about incorporating and interrogating other more established humanities disciplines, whose methodologies are rooted within colonial and Eurocentric power relationships.

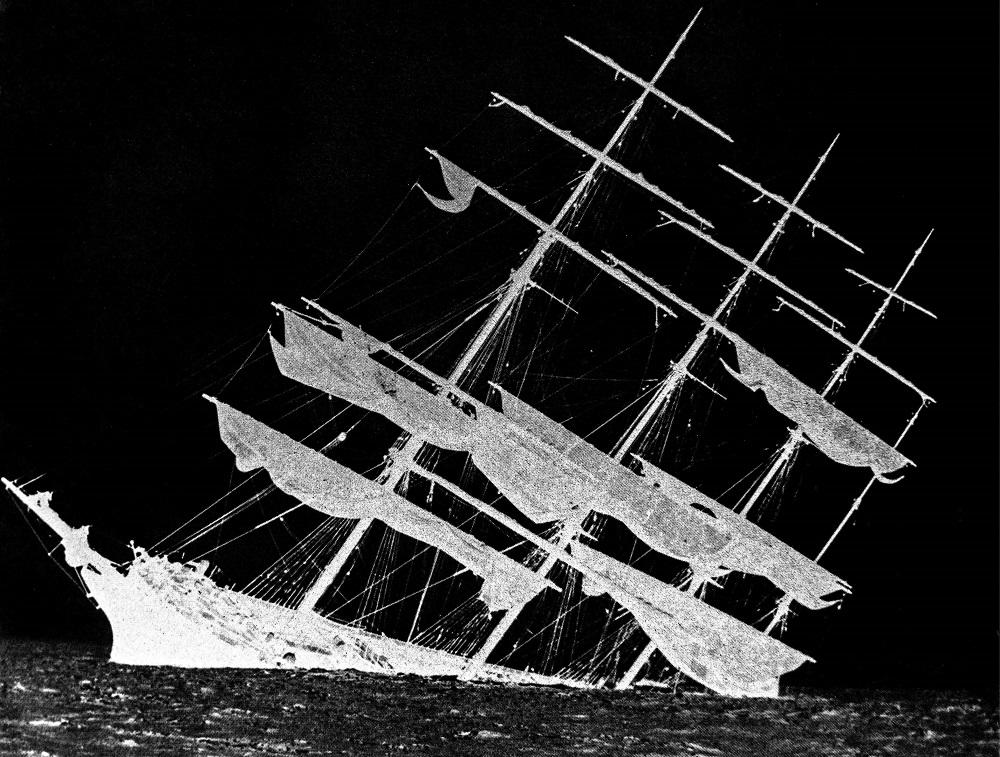

AK: The shipwreck is probably one of the most iconic subjects in Romantic art—from the work of JMW Turner to Nicholas Pocock. Pocock famously painted the drowning of the Dutton, an East India Company ship at the Plymouth Sound, and many others like the Queen Margaret. The latter’s wrecked image features in your work as well, as if you are casting a hyper-analytical, X-ray vision through the image. How did you wish to restructure the image of the shipwreck as an icon of romantic art to one of postcolonial recovery or, perhaps, restoration—as a qualitatively different gesture from, say, reparation?

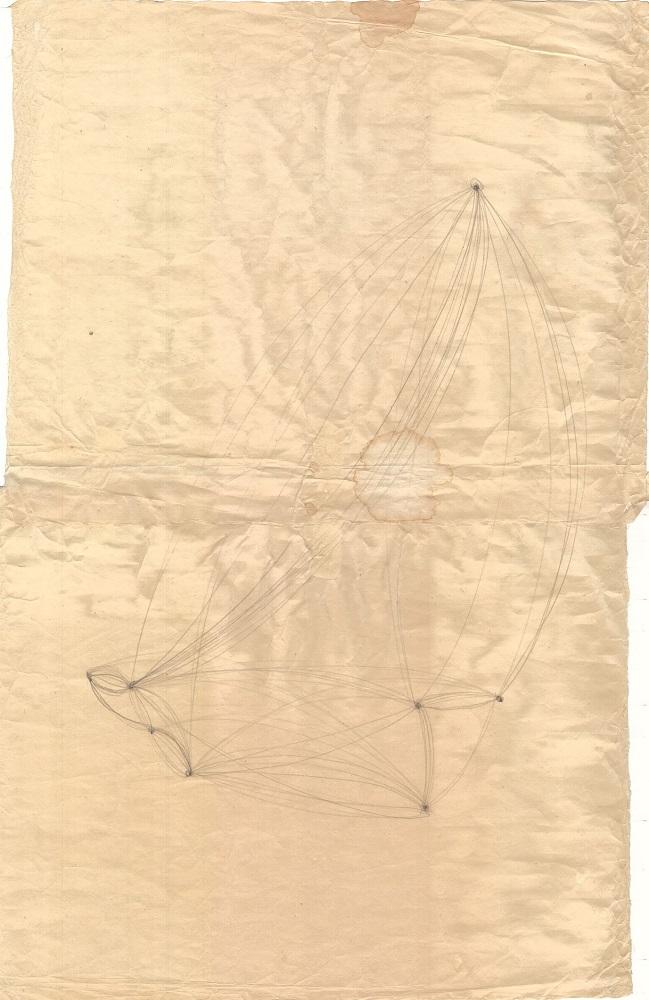

MC: I have been interested in shipwrecks for quite a long time and have been making work which considered this subject in relation to colonial era and Indian indentured experience—particularly in places like Fiji and Australia—which are connected to my own family’s diaspora history. For example, in Kikau Street (2016), alongside a meditative journey through my father’s now empty childhood home in Suva, I filmed at a nearby location. It was an idyllic beach where the ship Syria famously sank in 1884 after running aground on a reef, drowning many indentured migrants as well as sailors from India. I wanted to record this as a human tragedy but also to consider the shipwreck as a metaphor, for both human and systemic vulnerability. I also started considering maritime history more widely, for example, researching and exploring archival records for the ships which transported indentured labourers from India to Fiji—forty in total. So, that led to the making of the work 40 Ships, in which I retraced the journeys of my ancestors back to Northern India.

I began thinking about this global movement of goods and people, which grew largely in response to the burgeoning sugar trade. This was an exploitative system—displacing vast numbers of people around the world—as it replaced (but in many ways, replicated) slavery. It was, we might argue, the precursor to our contemporary globalised economy. It contained all of the latter’s inequalities, as well as the tensions between the movement of goods and capital alongside increasing methods of control over free movement for people. These are very powerful systems, with the attendant machinery of technology, wealth and power. However, for me, the idea of “wrecks and wreckage” intimates and speaks to the way power always has a weak spot. It is not, we find, completely impermeable. Shipping was the power of empire, but think of the damage a hole in the hull of a ship, or some human error/greed, such as, for example, overloading the ship, can cause.

Paradise Lost is available to view till 6 February 2022 as part of the Chennai Photo Biennale.

To read more about the third edition of the Chennai Photo Biennale, please click here, here, here and here.

All images from Paradise Lost by Mohini Chandra. Images courtesy of the artist and the Chennai Photo Biennale.