Farming the Revolution: Documentary Filmmaking as an Organising Tool

More than once in Nishtha Jain’s documentary, Farming the Revolution (Inquilab di Kheti, 2024), the camera captures the swathes of protesting farmers in Delhi through sweeping overhead shots, which illustrate the scale of the agitation against the farm laws proposed by the Government of India in 2020. Documenting the thirteen-month-long struggle, the film’s hundred-minute runtime is framed by unequivocal solidarity with the farmers. In a fairly conventionally styled but impeccably crafted documentary, the bird’s-eye shots are intriguing for reasons beyond their striking visuality.

Protesting farmers dot the literal and figurative landscape of Delhi in Jain’s documentary.

For one, this is a surprisingly unusual image from a movement that has been extensively recorded visually. The events were widely covered over news and social media and there is no dearth of published photographs that depict the magnitude of the protests. This particular vantage, almost pointillistic in its abstraction of the protestors, seems to be quite uncommon. Perhaps it is in its very paucity that the image might begin to reveal the place of the documentary form when its subject has already been well-documented. Jain seems to be toying with this query by deftly weaving together original cinematography with newsreel clips (particularly those tinged with their compliance to the state) and mobile-phone footage from the ground (which made its way to various social media platforms). Her attempt is thus to locate the film outside the dichotomy between the documentary form and reportage.

The aerial shot is also remarkable for what it invokes from the annals of the documentary filmmaking tradition. Nearly a hundred years ago, the Passaic Textile Strike, a similarly long workers’ struggle (January 1926–March 1927) in New Jersey, was chronicled in the documentary form by Samuel Russak. The angle in Farming is reminiscent, intentionally or otherwise, of the overhead shots in the eponymously titled Passaic Textile Strike film—recorded inconspicuously as the police attacked the protestors and media, destroying cameras on the ground.

The overhead shots in the Passaic Textile Strike film bears testimony to the brute force unleashed on the strikers and the media. (Image courtesy: International Workers Aid/Passaic Strike Relief Committee, The Passaic Textile Strike, 1926)

While by no means the first endeavour in radical filmmaking, the documentary on the Passaic Textile Strike was nevertheless a milestone in the tradition. The 1926 silent film is notable for its narrative of the strike which was mobilised, as Jacob Zumoff explains, to build solidarity through spectacle, and to raise funds to sustain the agitations. It echoes, in more ways than one, through Farming, offering a way to articulate the latter’s role in the movement it seeks to record.

Both the films, explicitly or implicitly, position their audience in the context of the movements, invoking, as Paula Rabinowitz puts it in her book, They must be represented: the politics of documentary (1994), a “performance within their audiences as much as within their objects.” Where Passaic does this by introducing the strike as a struggle of the “workers who make the cloth that clothes you,” Farming visually reinforces this idea by closing up on textures of food—the kneaded atta (flour), the fried onions and the endless glasses of milk.

Textures of revolt, up close.

In Farming, of the many featured protestors, the camera follows one in particular. Gurbaz, who is introduced to the audience through his own admission of being “indifferent” to the wider context, joins the protest and eventually takes on organisational duties in a farmers’ union. This transformation forms a crucial narrative device in the film, much like the prologue reel in Passaic that follows a quasi-fictionalised worker’s troubles. In his article on Passaic, Zumoff discerningly describes the film as depicting the strikers as “actors in their own drama, not just as subjects.”

As the seasons change, Gurbaz Sangha’s journey anchors the documentary, echoing the quasi-fictional Breznac family in the ‘Prologue’ reel of The Passaic Textile Strike.

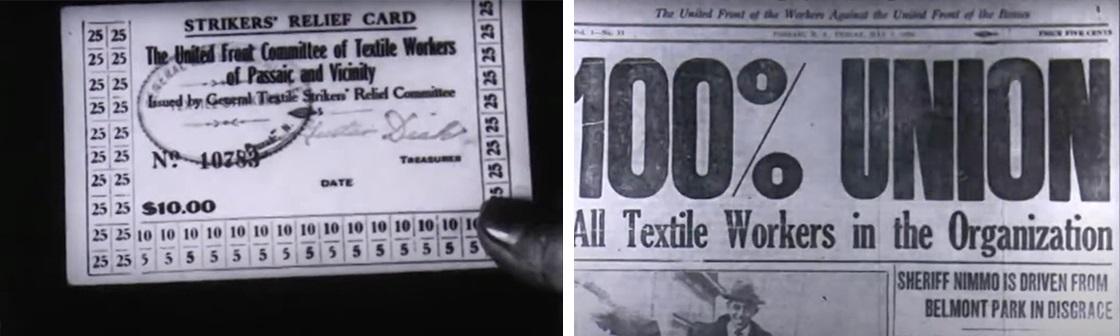

Both films categorically stress upon the role of women at the frontlines of the movement and highlight solidarity across different groups and communities. The logistics of political organising, too, play an important role in both narratives. In Farming, a union leader holds up a register tracking the daily usage of funds, while Passaic spotlights a relief card to explain how the strike was sustained. Another striking parallel is the emphasis on the organs of mobilisation—Farming points out that the protest had its own newspaper, Trolley Times, perhaps one of the lesser-known details for the general public. Passaic, of course, showcased the front page of the Textile Strike Bulletin.

The camera lingers on the material emblems of the logistics of protest movements. (Images courtesy: International Workers Aid/Passaic Strike Relief Committee, The Passaic Textile Strike, 1926)

There is a sense of perpetuity too that permeates both films. Even though Passaic ends in the middle of the strike while Farming sees the protesting farmers through their initial victory of the repeal of the farm laws, the latter makes it evident that the fight is far from over. The timing of the film’s release coincides with a renewal of the farmers’ agitations demanding the implementation of the promised legal assurances.

Farming the Revolution is remarkable not only in the documentation of the farmers’ protests, but in the way it relates to the movement itself and the possibilities it holds in terms of creative strategies of building and mobilising solidarity. The fight might not have been won yet, but the spirit of the farmers is infectious. “Let it take as long as it does, we are not going anywhere,” a protestor says. The movement stays.

Highlighting the political acumen of the movement, Farming the Revolution is an act of solidarity and it points to a tradition of using documentary film as tools to organise.

To learn more about Nishtha Jain’s work, revisit a conversation with the artist about her film The Golden Thread (2022). To learn more about films made on the farmers’ protest, read Kamayani Sharma’s essay on Gurvinder Singh’s Trolley Times (2023).

All images are stills from Farming the Revolution (2024) by Nishtha Jain unless mentioned otherwise. Images courtesy of the director and Akash Basumatari.