Everyday Images: Geoffrey Batchen's “Vernacular Photographies”

Vernacular photography refers to those everyday practices of image-making that occupy the realm of the domestic and the intimate rather than the monumental, historic and avant-garde. These have become an alternative lens through which contemporary readings of the medium are evolving.

Installation View of Suspending Time: Life-Photography-Death Curated by Geoffrey Batchen, Izu Photo Museum, Japan. This drew primarily from Batchen's own photographic collection with approximately 300 works on display. It included framed daguerreotypes and photographic jewellery as examples of genres and morphologies of vernacular photographic practices. (Japan, 2010. Image courtesy of Geoffrey Batchen.)

Geoffrey Batchen is a Professor of the History of Art and a Fellow of Trinity College at the University of Oxford. Batchen's work as a teacher, writer and curator focuses on the early histories of photography, often bringing it in conversation with the present cultural moment and contemporary art practices. In a paper titled “Vernacular Photographies” (2000), he argues for the multitudinous formations of “ordinary” photography that had been largely ignored by critical theory which concerns itself with the development of the medium as an artistic format. Such an expanded notion of photography includes, but is not limited to, family photographs, jewellery embellished with or made to contain photographs, scrapbooks, photographic memorialisations as well as various regional, indigenous and culturally situated practices of image-making.

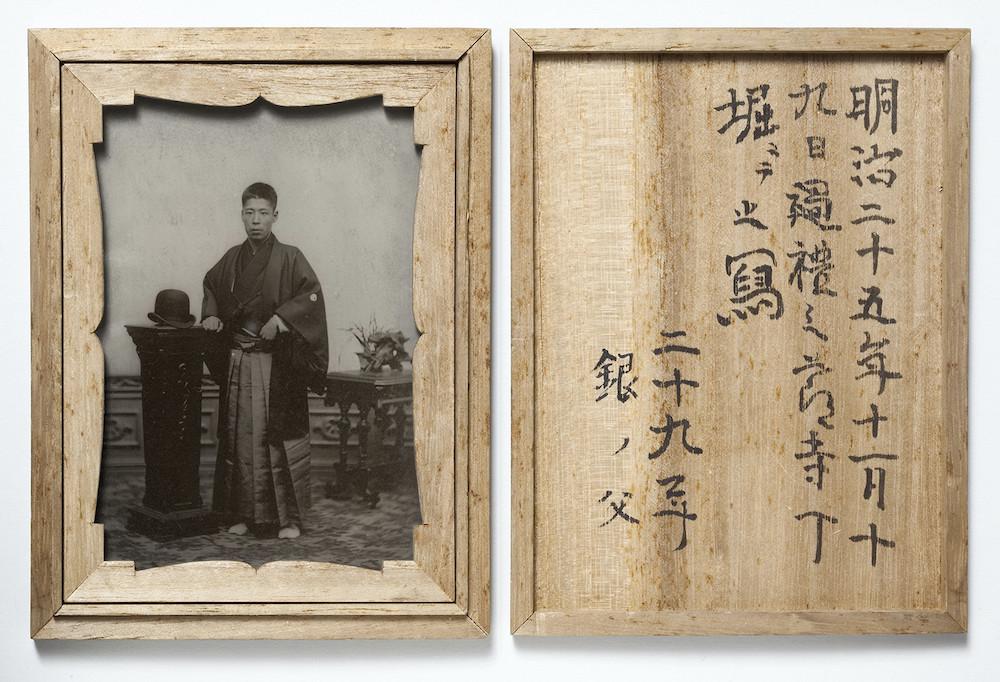

While the traditional art historical view of photography tends to focus on the content of the photographs, seeing them as transparent indexes of their referent, “Vernacular Photographies” argues for a reading situated within the study of material cultures. Taking cognisance of physicality and tactility is central to the comprehension of such an image, where the object is something to be held, folded, cut, pasted and caressed as much as it is seen through the eyes.

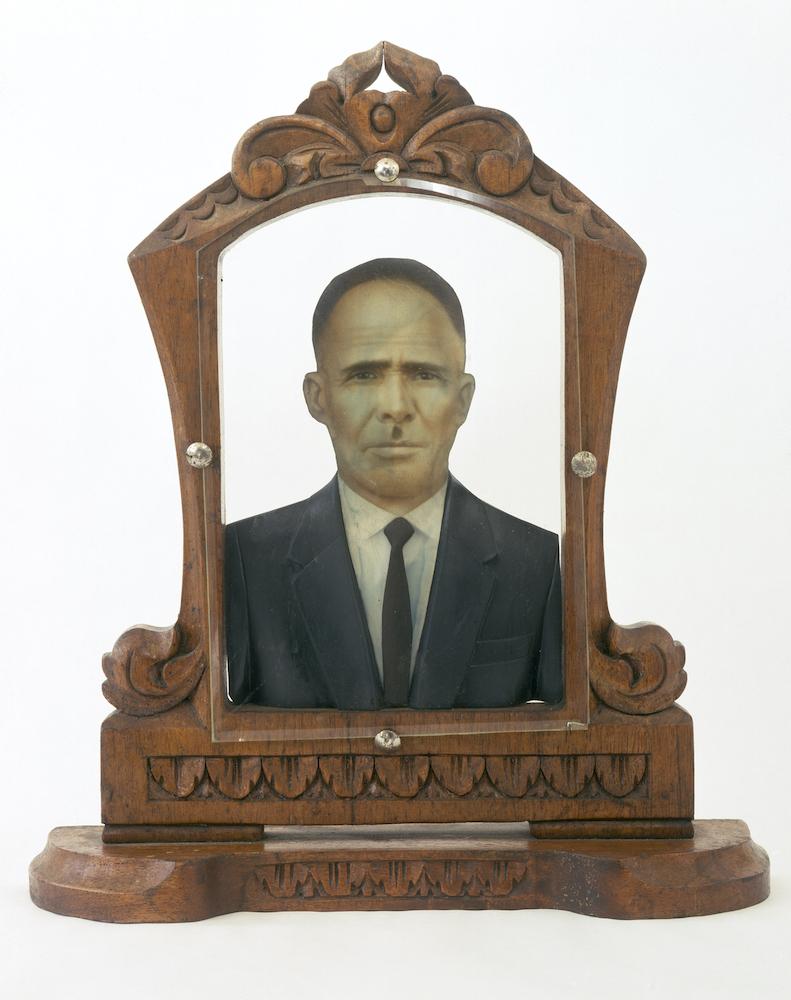

Portrait of a Man Wearing a Tie. (Unidentified Maker. Mexico, c.1950. Painted Gelatin Silver Print on Wood, Glass, Upholstery, Tacks and Wooden Frame. From the collection of Geoffrey Batchen.)

Batchen, in his text, cites the historical example of the daguerreotype—a photographic process on a silvered sheet of copper. As these early photographs were very delicate, they were encased in silk or velvet-lined leather cases, which were in turn embellished with embossed designs and painted landscapes. Batchen describes daguerreotype as multi-faceted objects with an inside and an outside, where the image was seen situated within the contexts of prosperity and family.

We are all witness to practices in contemporary times where photographs are freely altered and creatively utilised. Many investigations of regional studio photography, which often involve exotic backdrops, props and manual retouching, reveal a similar insight into the layered cultural ideals of aspiration, prosperity and social-mobility that occupy these popular images. Within these vernaculars, photography does not necessarily share an indexical relationship to any reality but is made to represent the aspirations, social relations and aesthetic sensibilities of its subjects, overlaid onto their photographic images.

Standing Man with Bowler Hat on a Pedestal. (Unidentified Maker. Japan, 19 November 1892. Ambrotype in Kiri-wood Case, with Inscribed Calligraphy in Ink. From the collection of Geoffrey Batchen.)

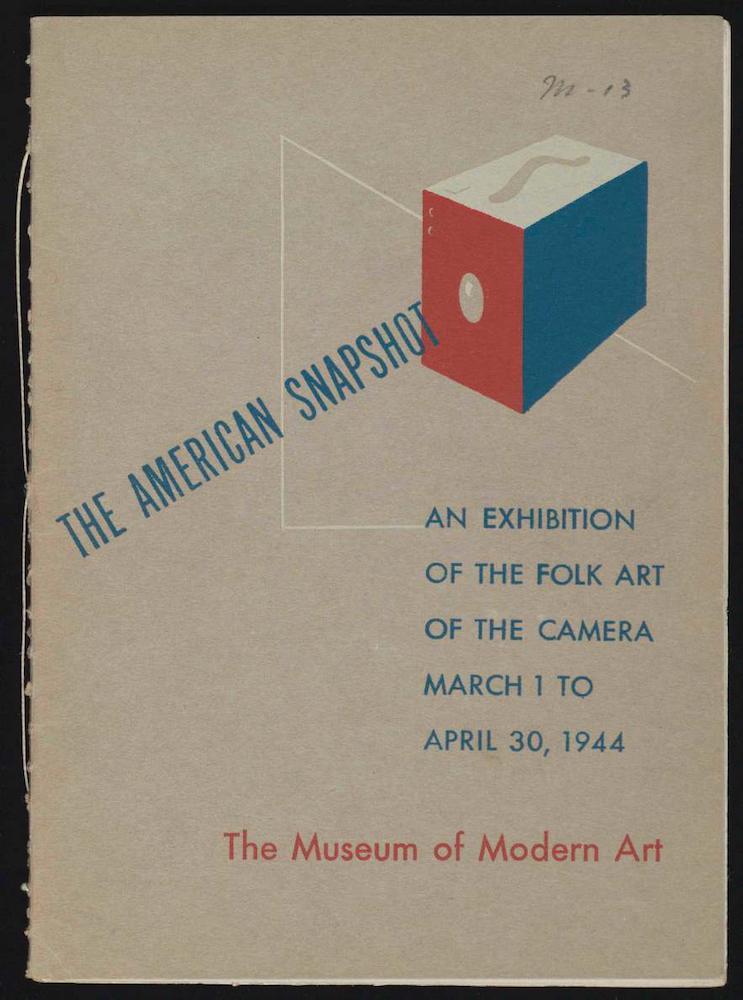

Cover of the Catalogue for The American Snapshot: An Exhibition of the Folk Art of the Camera. (New York, 1944. Museum of Modern Art, New York.)

These images then occupy the lives and homes of their subjects, memorialising them in their death and are often passed on to the next generation. Existing outside (for the most part) the artistic concerns of originality, authorship or styles of representation, these images instead serve as objects of ritual, as material anchors for migrant communities and surfaces for the projection of relationships. Various vernacular photographies across space and time thus become a valuable resource to understand cultural formations, aesthetic similarities and differences, and emotional and affective values. As a form of dispersed creative production, the idea of vernacular photography holds the potential to decentralise history from its official and canonised narratives. Consequently, it has informed the work of many important historians and writers concerned with subverting established methods of writing historiographies.

If you would like to explore vernacular photographic practices, please search for "Towards A Fugitive Photography: The Archives of Suresh Punjabi" and "Juju Bhai Dhakhwa: Keeper of Memories" in the Stories section.