On Witness: An Interview with Sanjay Kak

Sanjay Kak is a documentary filmmaker and writer whose interests lie in ecology, activism and resistance politics. His work has been focused on the conflict zone of Kashmir for several years now. Red Ant Dream (2013), his most recent film was based on the revolutionary Maoist movement in India and is the third in a series of films probing the workings of the “world’s largest democracy.” The other films in this trilogy include Jashn-e-Azadi: How We Celebrate Freedom (2007), a film on the Kashmiri freedom struggle and Words on Water (2002) on the people’s resistance against the Narmada dams.

In this interview, Kak speaks to us about being the editor and publisher of the book Witness: Kashmir 1986-2016: Nine Photographers featuring two hundred images archiving the history of a popular rebellion, and "freedom's terrible thirst."

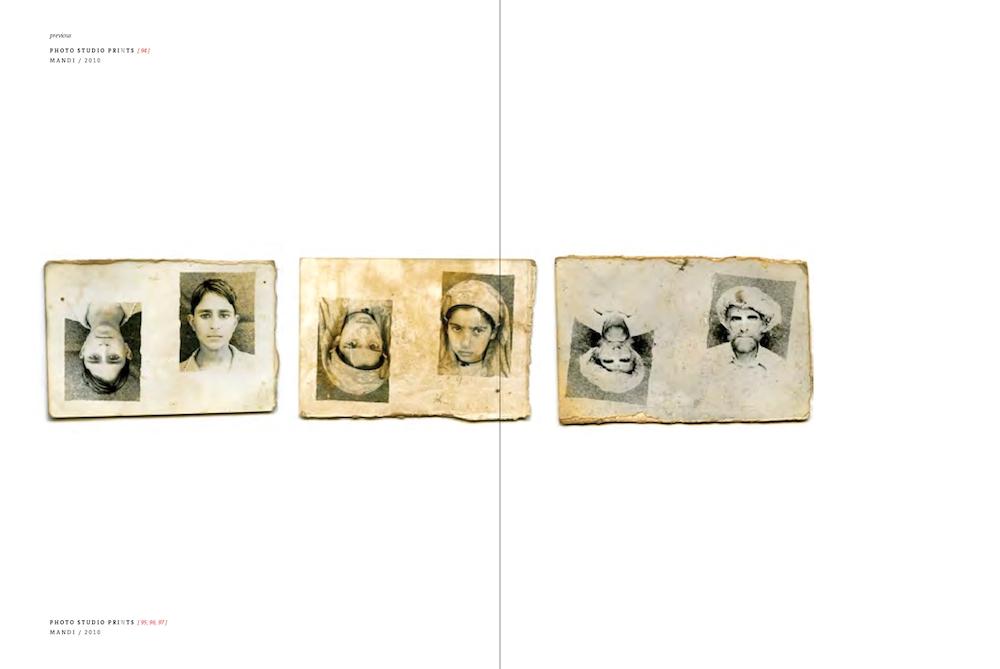

Anonymous Kashmiri Photo Studio Prints Collected from a Studio in Mandi in 2010. (From the collection of Sumit Dayal.)

Senjuti Mukherjee (SM): In your editorial introduction to Witness, you mention that words had become inadequate carriers of memory in Kashmir and it is under these circumstances that photojournalistic practices emerged. What role do photojournalists play in such a suffocated cultural landscape?

Sanjay Kak (SK): Photojournalism has played a remarkable part in keeping afloat public memory in Kashmir. This began in the early 1990s when the armed insurgency first broke out. For several decades, it was only these images—gathered erratically in the course of routine newsgathering—that survived as shared public “evidence.” In those decades, a terrible silence had been imposed on Kashmir, on its journalists, writers and human rights defenders. The conflict was being described to the world by outsiders: for the most part by visiting Indians, and largely from the lens of the Indian state.

Burial Processions, Lower Munda, Qazigund. (Photograph by Javed Dar. Kashmir, 2008. Digital.)

Kashmiri journalists, writers and filmmakers began to step out of the shadows—to speak out about what was really going on there—much more recently. I would say they first gathered real significance from around the time of the massive public protests of 2008. But all along, it was Kashmiri photographers who had been doing what we have only now begun to recognise as the critical work of documenting contemporary history.

Protest Outside Shrine, Chrar-e-Sharif. (Photograph by Meraj Ud Din. Kashmir, 1995.)

SM: What were some of the editorial strategies/positions that you adopted during the selection of the works featured in the book? Was there an archival instinct driving this process?

SK: The archival was in fact the primary trigger behind this curation. I came across the work of some of the photographers while researching for a film in Kashmir. There were hundreds of images in these individual, fairly haphazard collections. This was the output of photographers who shot news images, as part of the everyday grind of freelancers, earning a bit of money and moving on. Yet when I first saw their images, they spoke so loudly about the 1990s and 2000s. Reaching out to these individuals, overcoming their skepticism about the historical value of the images and persuading them to see it as part of a common heritage was not easy… Then came the flood of 2014, which overwhelmed Srinagar city and large parts of the Kashmir valley. Several photographers—including those whose work I had seen and admired—lost work while others suffered extensive damage. By then I was frantic that this work be secured in some way and made more public…

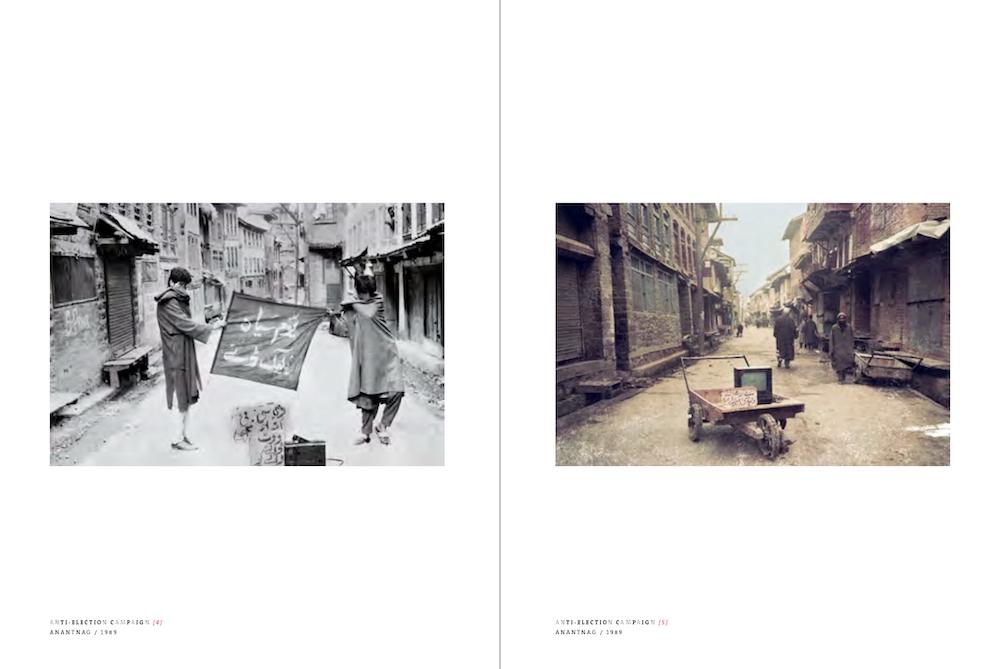

Anti-election Campaign, Anantnag. (Photographs by Meraj Ud Din. Kashmir, 1989.)

The other major shift in editorial position—which somewhat displaced the early archival intent—came much later, somewhere in the middle of getting the images together. I realised that while the book was obviously about Kashmir, it also had to be about the photographers themselves. Who were they, where did they come from? Over three decades the photographers had also changed. Photography—and not simply images to feed the insatiable appetite of the media—had found a foothold for itself in Kashmir. This drew me to the work of the younger photographers who feature in Witness. For them playing a part in history was important, but the ways in which those narratives could be made was as important.

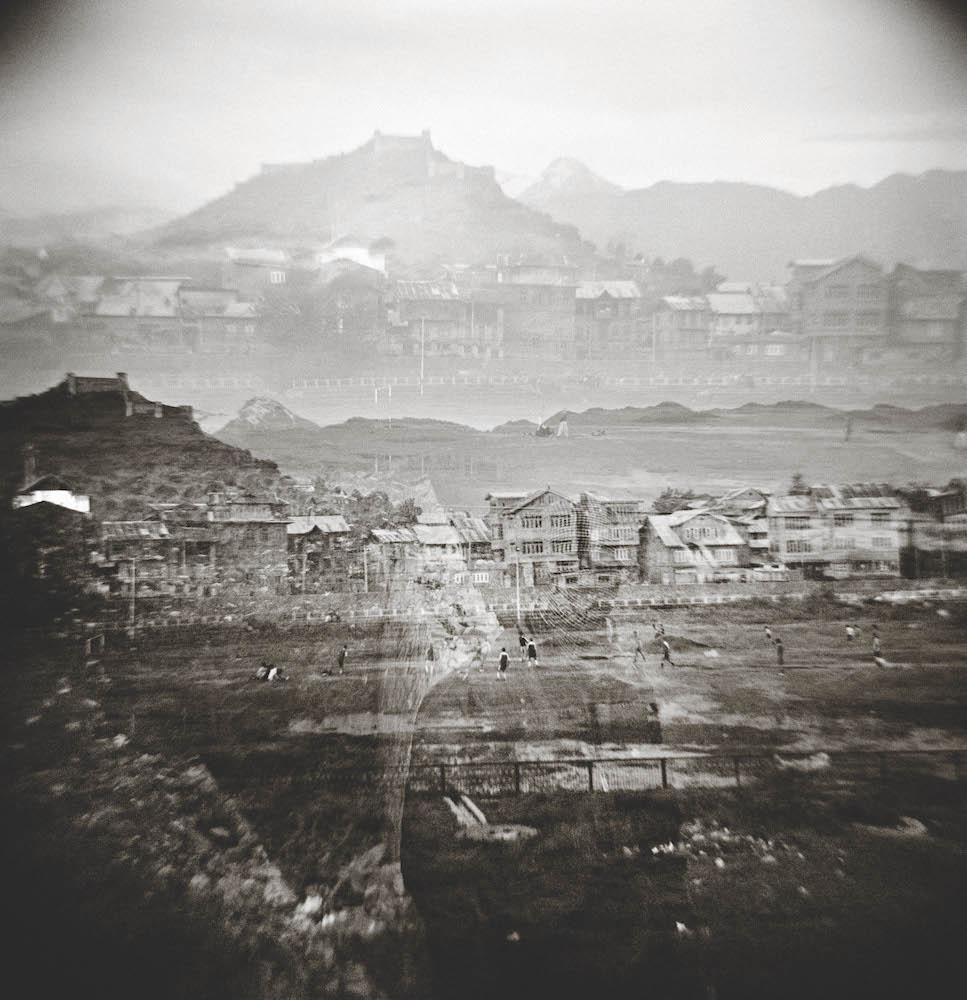

Memories of Makhdoom Sahib, Srinagar. (Photograph by Sumit Dayal. Kashmir, 2010. Kodak Tri-X Film, Shot with Lomo LC-A.)

SM: Did you/the practitioners have to straddle the demands of media organisations in the making of the book? Did you consider the place of social media at the time of its making?

SK: I came to the making of this book from a background in independent documentary film, a practice that is almost obsessive about guarding its turf from interference. I presumed that doing a photobook would be no different—that our own curatorial and editorial instincts, for better or for worse, would set the tone all the way down the line. I also learned quite quickly about the way publishing works in India, and figured out that no regular publisher would be interested in dealing with the impractical demands of a 400-page photobook with a complex design. And that too about Kashmir! That is why I decided to self-publish it and this led to the creation of the Yaarbal publishing imprint. Every step was a learning process: I also figured out the stranglehold that the book trade has on distribution, especially when it comes to books from smaller, independent, more edgy publishers. So, armed with the foolhardy courage of having distributed my own documentary films, we decided to self-distribute the book. (And have not done too badly either…)

This naturally segues into the second part of your question: I do not think it would have been possible to distribute the book independently if we did not have access to the resources of social media. For my films I have, over the years, made that journey from email groups to blogs and then to Facebook. And now there is Instagram. At literally every step, social media gave us the ability to find our audience. And of course, simplified e-commerce allowed us to turn potential reader interest into revenues...

Prayers for a Brother, Baramulla. (Photograph by Showkat Nanda. Kashmir, 2014. Digital.)

SM: How do you perceive Witness now, given the changed status of the region, since publication in 2017?

SK: I see the change in status following the revocation of Article 370 in August 2019 as a legal change, as the final desecration of a constitutional promise long trampled over. The fact that it was accompanied by a paranoid level of militarisation, an unbearably long shut down and an internet siege made things much worse no doubt. But essentially what we are seeing is a continuation of the same history that Witness tries to evoke. If anything, the archive that we have put together within the folds of the book flows even more seamlessly into the present.

Muharram, Hassanabad, Srinagar. (Photograph by Syed Shahriyar. Kashmir, 2015. Digital.)

All images from Witness: Kashmir 1986-2016: Nine Photographers. New Delhi: Yaarbal Books, 2017.