Both Poison and Cure: Christopher Pinney’s Seven Theses on Photography

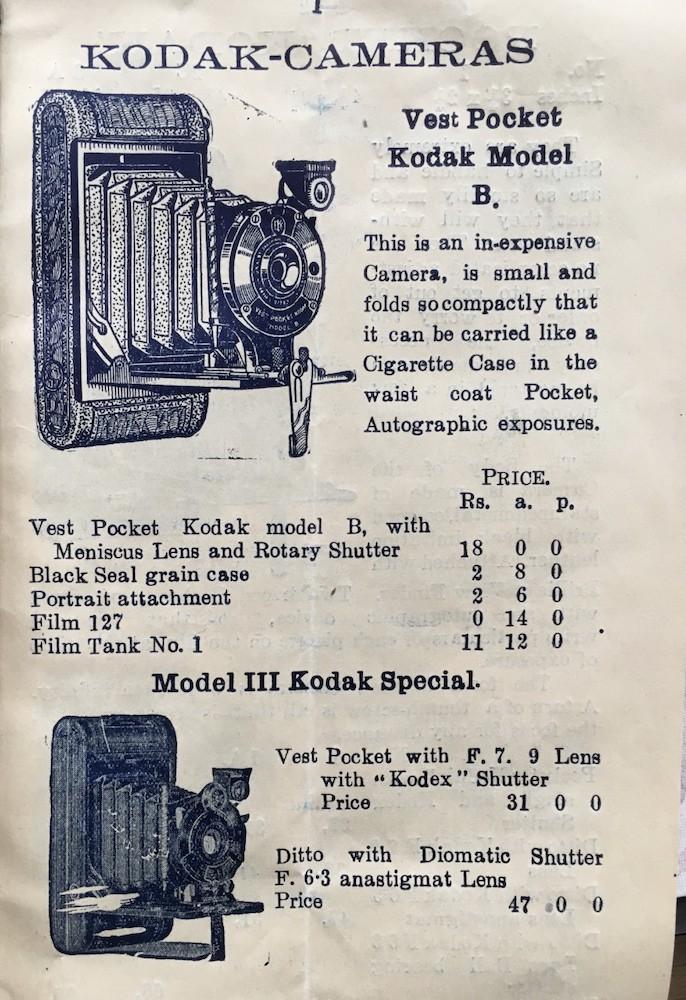

Vest Pocket Kodak Camera Advertised in a Catalogue Issued by a 1930s’ Lahore Dealer. As Walter Benjamin wrote in 1931: “The camera is getting smaller and smaller, ever ready to capture fleeting and secret images.” (From the collection of Christopher Pinney.)

In this continuing discussion on Christopher Pinney’s article “Seven Theses on Photography” published in the journal Thesis Eleven in 2012, we open up the last four theses and reflect on how these ideas might apply to current practices.

The referent always adheres

Pinney insists on the photograph as index of the “pro-filmic.” In the previous post, we had defined the “pro-filmic” as the scene appearing before the camera during the event of a photograph. Responding to debates around the relationship between photographs and reality, and the claims of representing “truth” made by certain kinds of documentary photography, Pinney insists that the nature of photography dictates that the visual reality before the camera (pro-filmic) is captured in the photograph. Thus, while a photograph representing an event may be entirely staged or manipulated, it remains an index of this precise event of staging. A photograph is always an image of something, which leaves an impression on the photographic medium, and this relationship between the image and referent should remain central to the practice and theories of photography.

Photography is prophetic, acting in advance of social reality

In line with the ideas of Roland Barthes, and more recently that of photography theorist Ariella Azoulay, Pinney makes the claim that photographic representations trigger individual and collective imaginations to produce and reveal newer subject positions in society. In her book The Civil Contract of Photography, Azoulay examines images of refugees and stateless peoples to argue that the act of being represented gives them access to a “citizenship of photography.”

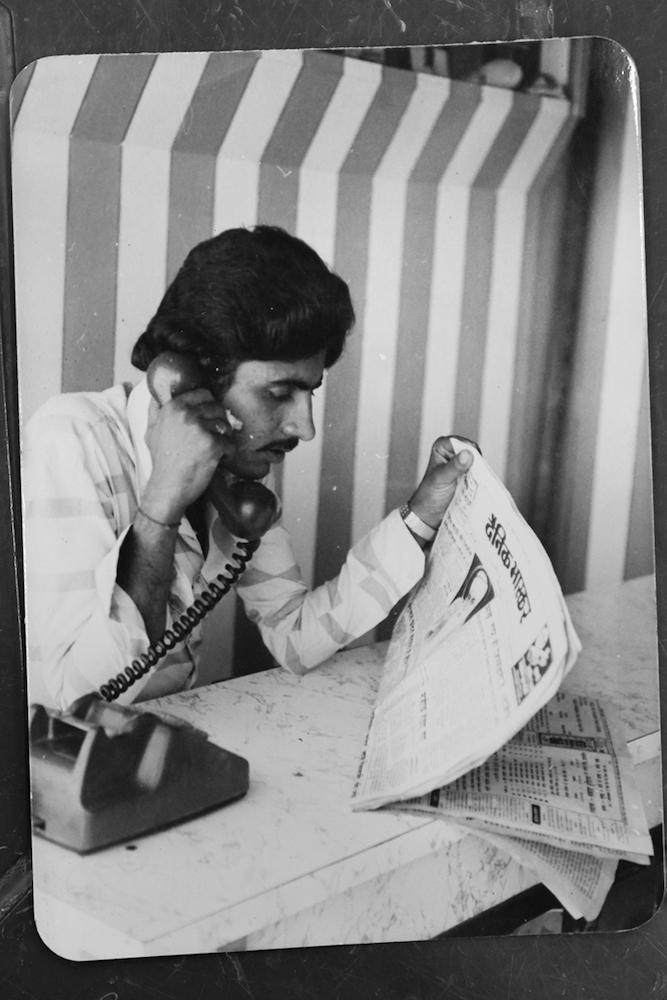

Pinney illustrates his thesis by looking at how Indian society transformed from a largely collective self-articulation to more individualised notions of selfhood and citizenship during the nineteenth-century. He argues that this process is reflected in and aided by the aesthetic assertion of singularity through the production of photographic images of one’s body as separate from others; as well as the techniques and apparatus of nineteenth-century anthropological photography which were more favourable to singular portraits than group photographs.

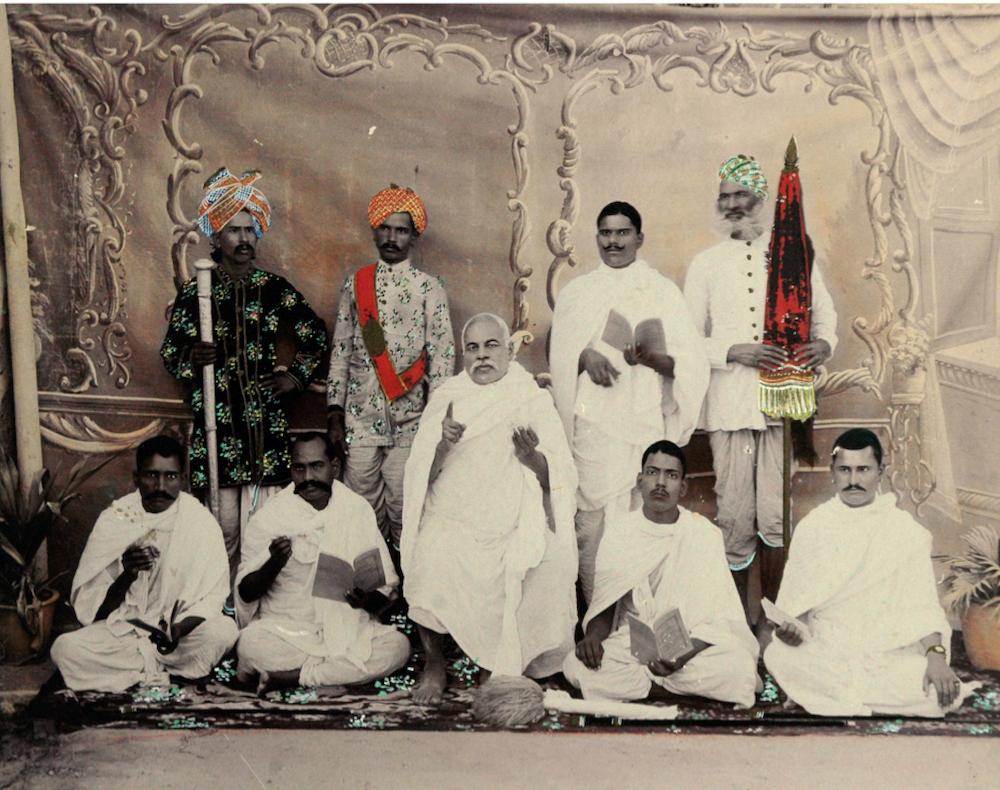

A Group of Jain Pilgrims or Monks. As photography rendered everyone equally, it was necessary to over-paint their servants in order to make visible their continuing worldliness. (From the Alkazi Collection of Photography.)

It causes disturbance, prying aura from its shell

Pinney argues that photography, through its inherent quality of representing without discrimination, upsets established norms and social structures grounded in difference. Referencing the effects early photography had in colonial India, he points out how a multiplicity of social hierarchies were disrupted through the act of photographic representation which was radically egalitarian.

Self-Portrait by Suresh Punjabi, Suhag Studio. (Madhya Pradesh, c. 1978. Image courtesy of Suresh Punjabi.)

It is both poison and cure

In his final thesis, Pinney looks towards the future of thinking about photography. He describes the tension between the singular notion of photography’s history—where it is perceived as a “cure,” an organising principle through which subjects are created and controlled; as against the idea of plural photographies that take on a multiplicity of forms and implications in the contingency of its practice. He asks,

“How do we account for the divided and apparently contradictory nature of photographic practices if it is indeed a photography (singular)? Answering this must involve the foregrounding of the changing nature of apparatus: the single descriptor ‘photography’ also names a succession of techniques which are still of course in the process of becoming... Grasping the protean transformations that occur under the descriptor ‘photography’ is the starting point for an understanding of photographic practices.”

Pinney’s article encourages a deeper discussion of photographic principles and the meanings they continue to produce in society. The field of photography remains a fertile ground for building frameworks to understand contemporary image cultures within the histories and socio-political contexts that produce them.

In case you missed the first part, please search for “On a World-System Photography: Christopher Pinney’s Seven Theses on Photography” in the Stories section.