In a Bittersweet Land: William Gedney in India

Early in his career as a United States of America-based documentary and street photographer, William Gedney arrived in India in November 1969 with the intent to travel to Kolkata. When his train—having departed from Delhi—stopped at the Varanasi railway station, Gedney made a spur of the moment decision to disembark. Abandoning all other plans for his time in the country, he remained in this city, photographing it extensively for the next fourteen months.

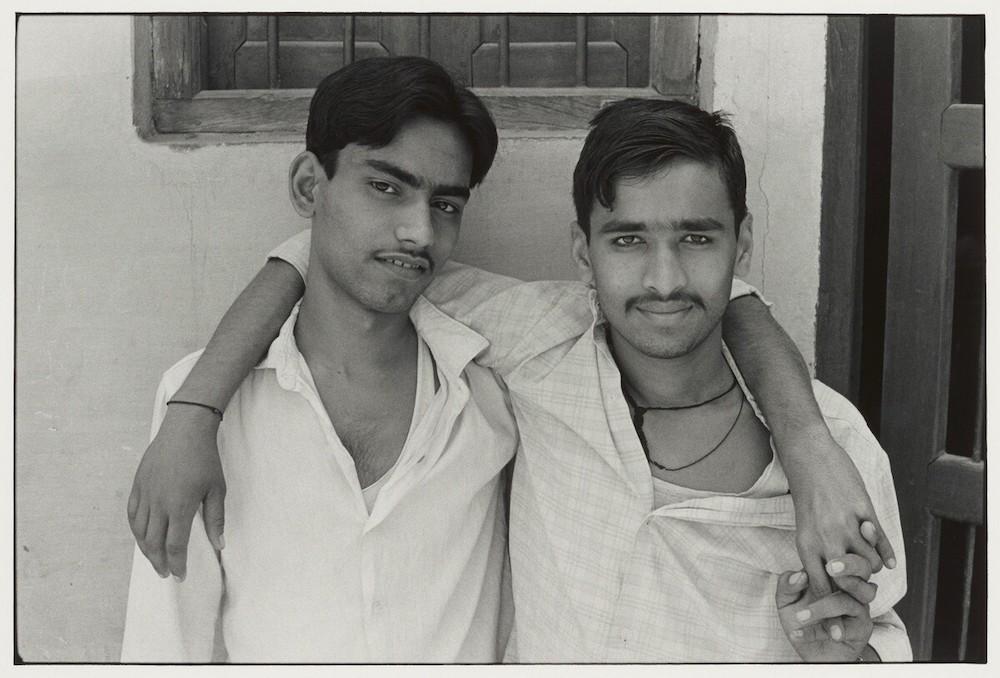

Men Holding Hands. (Varanasi, 1969–71. Image courtesy of William Gedney Photographs and Papers, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University.)

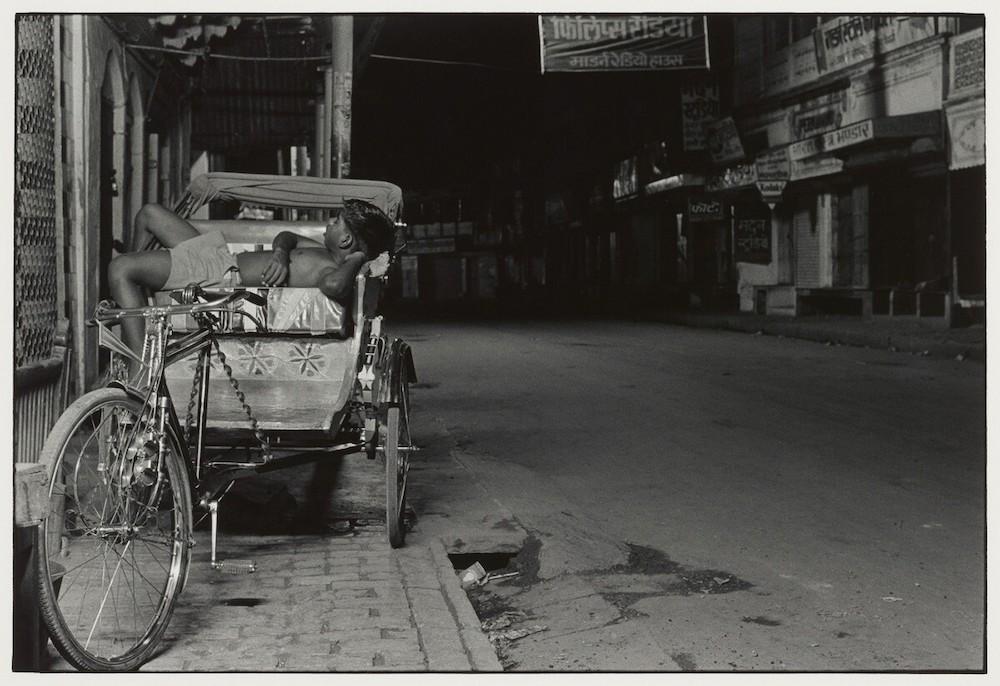

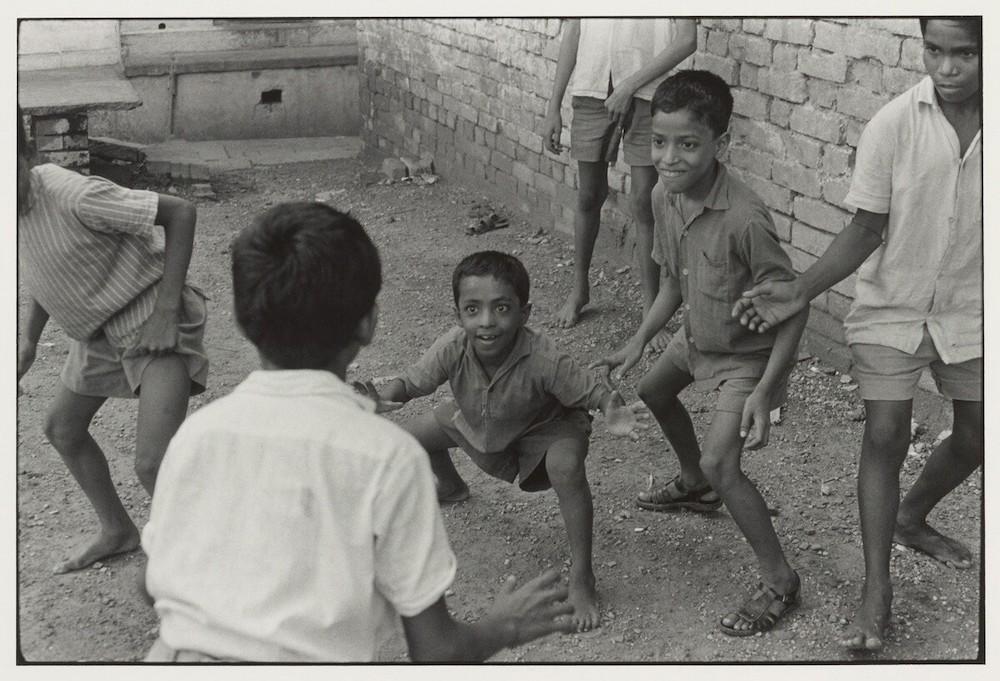

Along with his camera, Gedney brought with him a photographic vision characterised both by a sympathy towards the downtrodden and an attention to the male form. Informed by the turbulent and revolutionary ethos of 1960s North America, his camera inevitably drifted towards the subaltern—the street dwellers, the labourers and the rickshaw pullers on the streets of Varanasi. The pictures in this collection thus offer an intimate gateway into the lives of working-class Indian men and a visual exploration of their relationship with their male peers and the city.

A Cycle-Rickshaw-Wala Sleeps in his Rickshaw at Night. (Varanasi, 1969–71. Image courtesy of William Gedney Photographs and Papers, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University.)

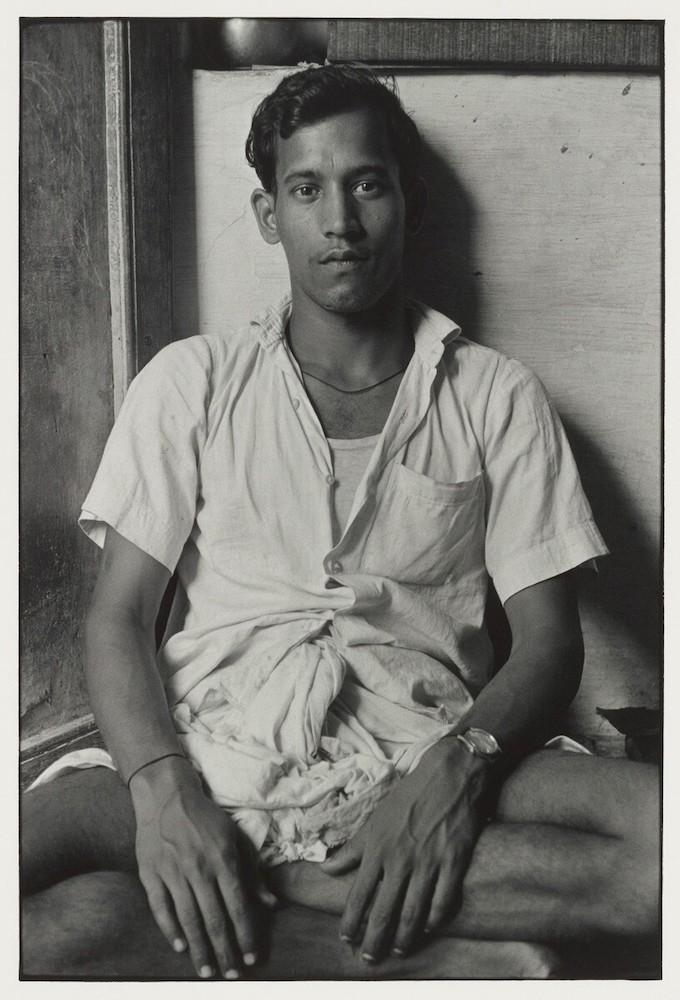

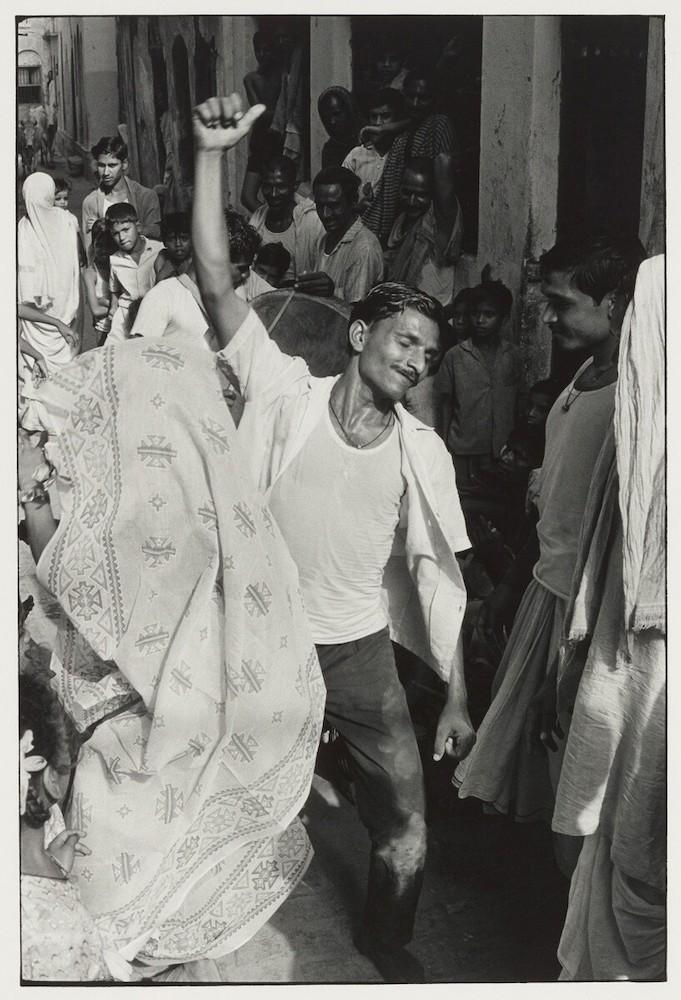

While women are certainly not absent from this collection, they are rarely portrayed with the keenness that Gedney accords to his male subjects. His struggle with the expression of his own sexuality—which he kept secret till late in life—heavily informed his work. The sensual physicality of his portraits and his fascination with male friendships, expressed through the tactile holding of hands and intertwining of fingers, recur as tropes through the collection. In Gedney’s hands, the camera strives to make visible an affective masculinity rendered through the male body that is candidly relaxed, joyous and intimate. These overturn the expectations of “manliness” expressed through action and vigour, with its gaze simultaneously permeated with a sense of (queer) desire.

An Intimate Gaze. (Varanasi, 1969–71. Image courtesy of William Gedney Photographs and Papers, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University.)

His predicament also gives him an acute understanding of marginalisation and a deep empathy towards the oppressed. In a moment of profound solidarity with a Dalit man bullied by his neighbours, he writes, “The despair inside. High caste spoiled kids mocking an age-old water carrier, cruelly, cruelly, cruelly. He sits down and holds his head, accepting it, not realizing that I understand…” Whether Gedney truly understood the specificities of caste discrimination or not, he certainly understood persecution and the pain of invisibility. As his experience of this “bittersweet land” increasingly turned “bitter,” he resolved to “never let that bitterness show in my work.”

Children at Play. (Varanasi, 1969–71. Image courtesy of William Gedney Photographs and Papers, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University.)

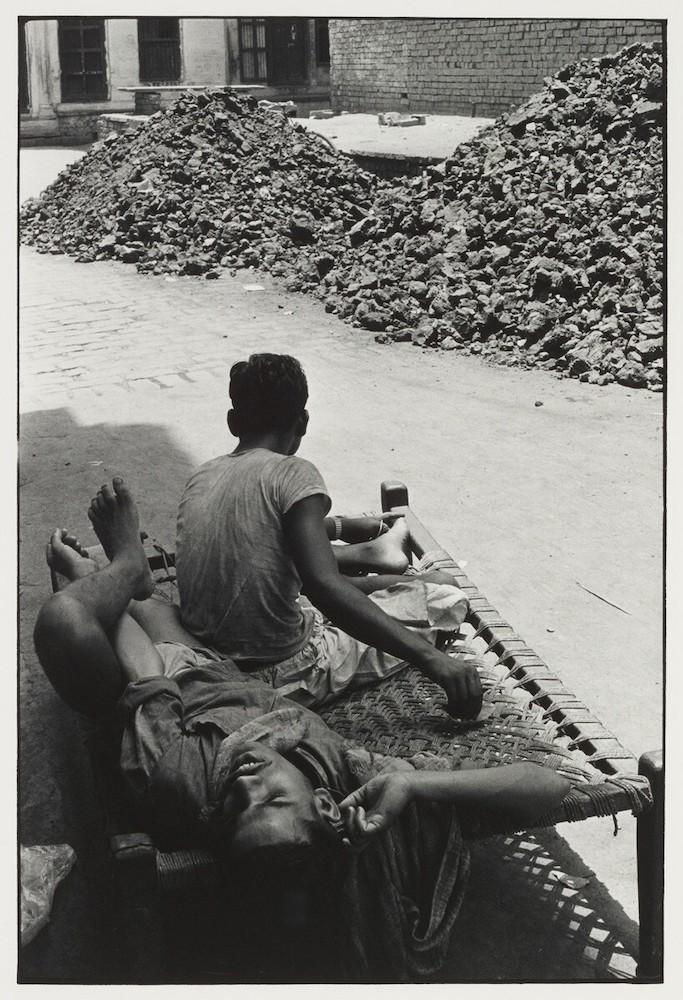

In refraining from the vicious social realities that define the lived experience of India, Gedney took recourse to exercising an overlaid attention to form. The body becomes reminiscent of “Exaggerated postures of Indian medieval sculpture” which he went on to observe “…are not artistic fantasy but stem directly from the physical stance and movement of the Indian’s body.” The images coincide with Gedney’s observations of the peculiarities of posturing in Indian culture. He noted, “The physical bearing of Indians is uniquely different from that of Westerners… Limbs seem capable of an endless variety of curved relationships. Hands and fingers held in the most intricate gestures.”

A Moment of Respite. (Varanasi, 1969–71. Image courtesy of William Gedney Photographs and Papers, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University.)

His other bodies of work seem to be similarly informed with this concern for the oppressed and the male form. In rural Kentucky, Gedney befriended and extensively photographed a family of coal miners. He documented the counterculture revolution in San Francisco. On his return to Brooklyn, New York, he produced beautiful photographs of the Gay Pride parade. The intimate portrayal of his subjects in these works is simultaneously embedded within critical moments in the history of the United States of America. In contrast with the immediately identifiable historical and contextual markers that Gedney’s American photographs provide, the lens of familiarity characteristic of his photography here is juxtaposed along with a lens of difference, coloured by a textualist approach in India.

A Man Dancing during a Celebration on the Streets. (Varanasi, 1969–71. Image courtesy of William Gedney Photographs and Papers, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University.)

This double mediation produces a timeless and ahistorical image of Varanasi. The subaltern Indian male body thus transforms from a subject into an image. It is a sympathetic image, but one that is fixed in time and appearance nevertheless. By recasting masculinity in an intimate frame while simultaneously perpetuating Orientalist readings of India, Gedney’s Varanasi collection intertwines the discourse on sexuality, race, familiarity and difference in complex ways.

To explore more of William Gedney’s work, please search for “Streets of Intimacy: William Gedney's Banaras Photographs” in the Albums section.

All images by William Gedney. From William Gedney Photographs and Papers, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University.