Imperial Projects of Exploration: Louis Rousselet in India

An artist and traveller, Louis Rousselet set sail from Marseilles, France and arrived at the bustling harbour of erstwhile colonial Bombay in the year 1864. Within weeks, Rousselet visited the Dabhoi Fort in the present-day Vadodara district of Gujarat. As he contemplated the picturesque ruins in front of him, Rousselet was overcome by a sense of regret. The landscape convinced this skilled painter that “…it would be impossible to continue (his) explorations (in India) profitably without the assistance of that art,” that is, photography. On his return from Dabhoi, Rousselet promptly obtained equipment from a provider in Mumbai and put himself to learning how to use the camera.

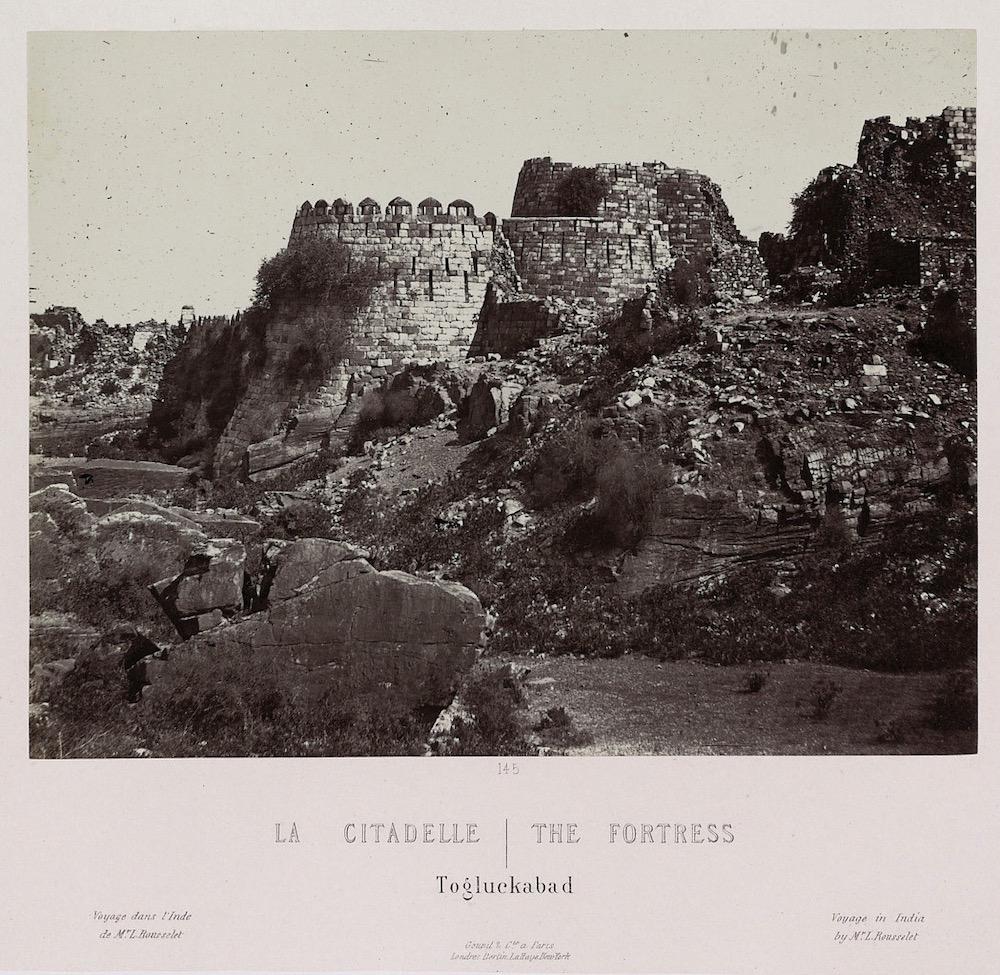

While there is no photographic evidence of Rousselet returning to the Dabhoi Fort to test his newly acquired camera skills, this photograph of the fortress of Tughlakabad registers his fascination with ancient ruins—a key thematic of Romanticism and the picturesque.

Within decades of the invention of the daguerreotype in his home country, this French traveller acquired the necessary technical skills and was initiated into photographic practice in British India. Rousselet’s conclusion that his existing artistic skills were inefficacious in the face of Indian landscapes and the urgency to switch to photography tells the story of the early photographic aesthetic that reframed imperial visions of the colony and the metropole in significant ways.

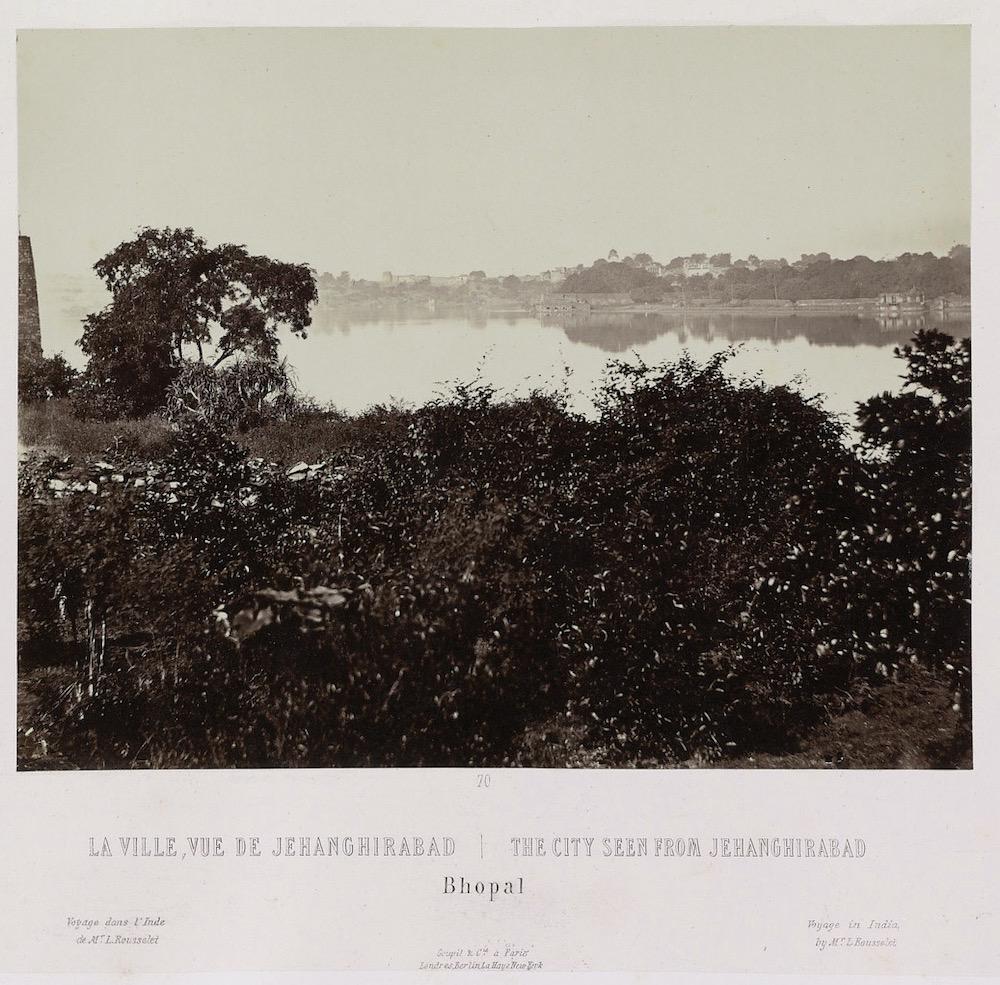

A scene of the city of Bhopal foregrounding the central lake, taken during Rousselet’s travels across Central India.

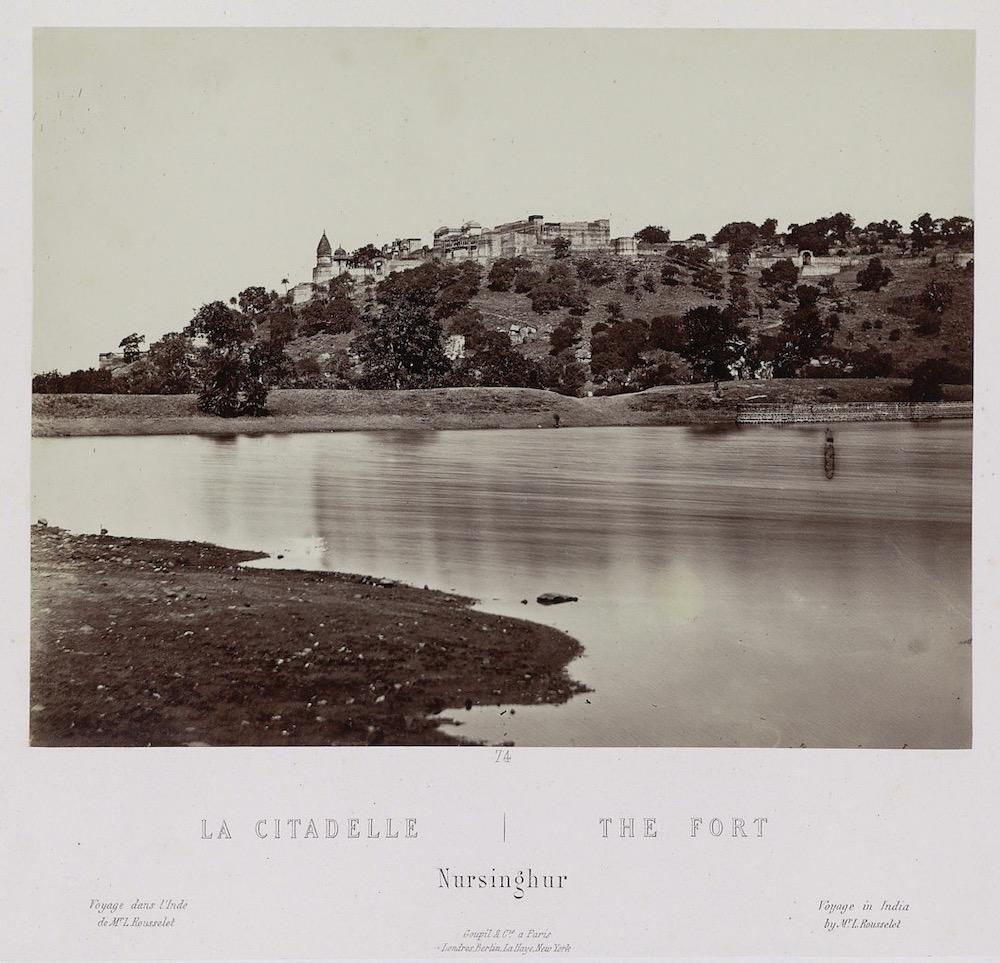

Coloured in colonial curiosity and imperial projects of exploration, the picturesque emerged as the dominant aesthetic of early photographic practice. Essentially a painting style of British origin that developed in the late eighteenth-century, the picturesque can be defined as a visual ideal replete with tropes of discovery and representations of untamed, “natural” sceneries. This form invokes that which is worthy of being a picture, offering an aesthetic framework from within which actual landscapes—in the British countryside as well as in the colonies—were eventually being viewed.

The Nursinghar Fort from across the Parshuram Sagar lake, a classic setting for framing the picturesque view of the city and a recurring trope in Rousselet’s photographs.

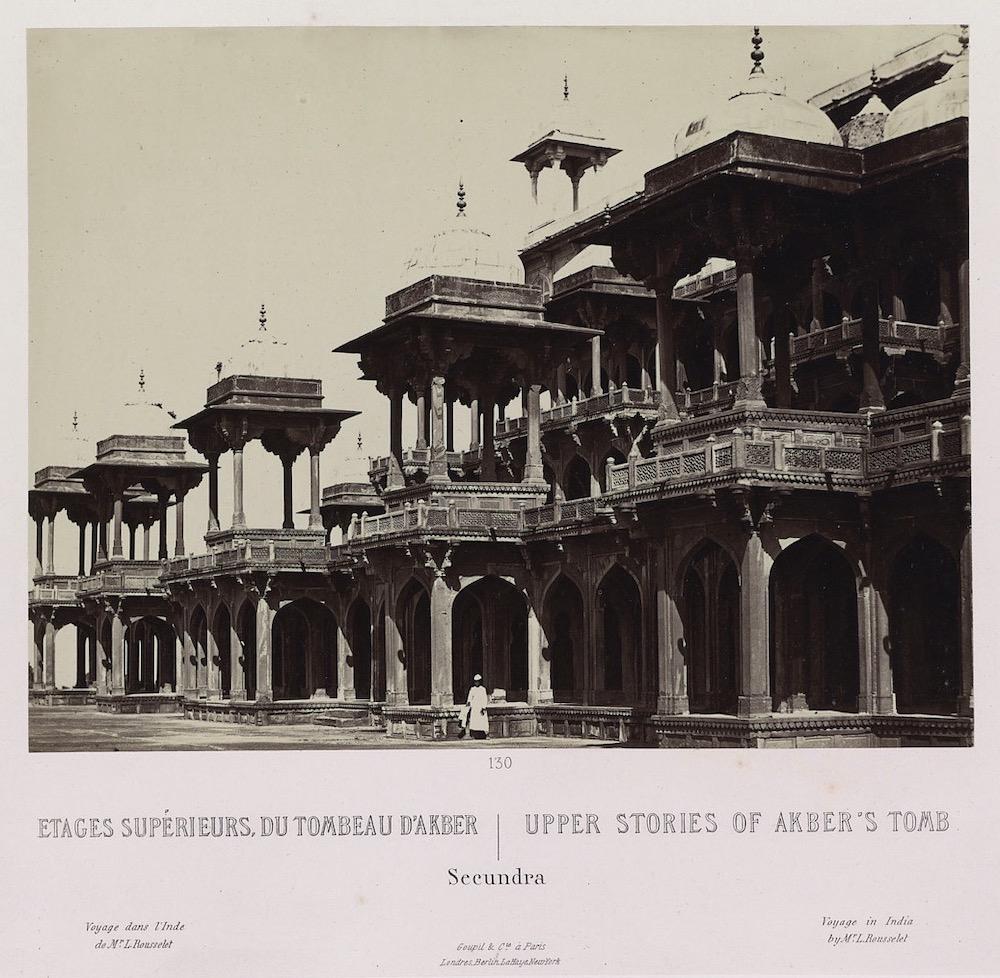

Art historians have often argued how European photographers employed the picturesque to further colonial agenda by producing images of the Indian landscape as benign and unexplored, readily available for commercial exploits and imperial quests. With the establishment of Archaeological Survey of India in 1870 under the directorship of Alexander Cunningham and the importance he accorded to photographic surveys, the visual amalgamation of colonial techniques of knowledge formation with art historical practices was particularly heightened.

As an archaeologist, Rousselet paid special attention to ancient buildings and architectural heritage in his work. Here he captures the upper stories of Akbar’s tomb at Sikandra near Agra.

The application of this aesthetic mode in the colonies however also underscored a tension between the picturesque at home and that found in “exotic” lands. While painters and photographers such as Rousselet travelled to the colonial outposts in search of difference, the aesthetic they deployed was based in Romanticist notions. Such artists dislocated unpeopled and deserted sceneries and equally exoticised the English countryside as the great bazaar in Ajmer, Rajasthan, for instance. Thus, a complex combination of wanting to capture specific histories of the Indian landscape through an aesthetic that constantly sought to erase such specificities emerged.

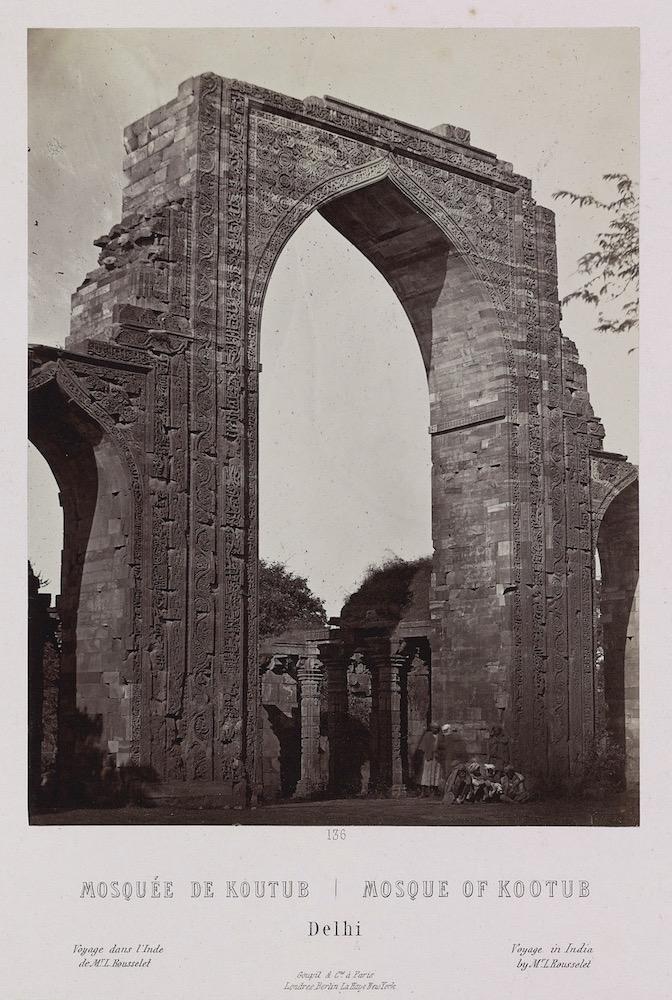

Ruins of the Qutub mosque in Delhi with a group of men posing close to it. While the strategic placement of natives gave conception of scale to the viewer, the presence of the brown bodies also localised the scene: a reminder of where the photograph was taken and a marker of difference.

As Rousselet and other photographers like him moved through imperial networks spread across the globe, transporting camera techniques, visual frames and photographic prints; their lens often returned the gaze of the colonial picturesque back at the metropole. The photographic picturesque thus worked in two pronged ways. It captured degrees of imperial order and control by mediating the impulse to “discover” the world. But through the homogeneous rendering of colonial and British landscapes, it also reflected what visual anthropologist Deborah Poole has referred to as the “Aesthetics of the same.” As the picturesque compelled photographers to “similarly” frame the natural sceneries, ancient ruins and the scantly populated countryside in Britain and colonial India alike, it made visible the fragility of notions of difference between the colony and the metropole that were used to justify colonial rule.

All images by Louis Rousselet. India, 1865–68. From Louis Rousselet Photographs of India, The Getty Research Institute Digital Collections.