Imperatives of Commercial Photography: Reading the Works of Vivek Das

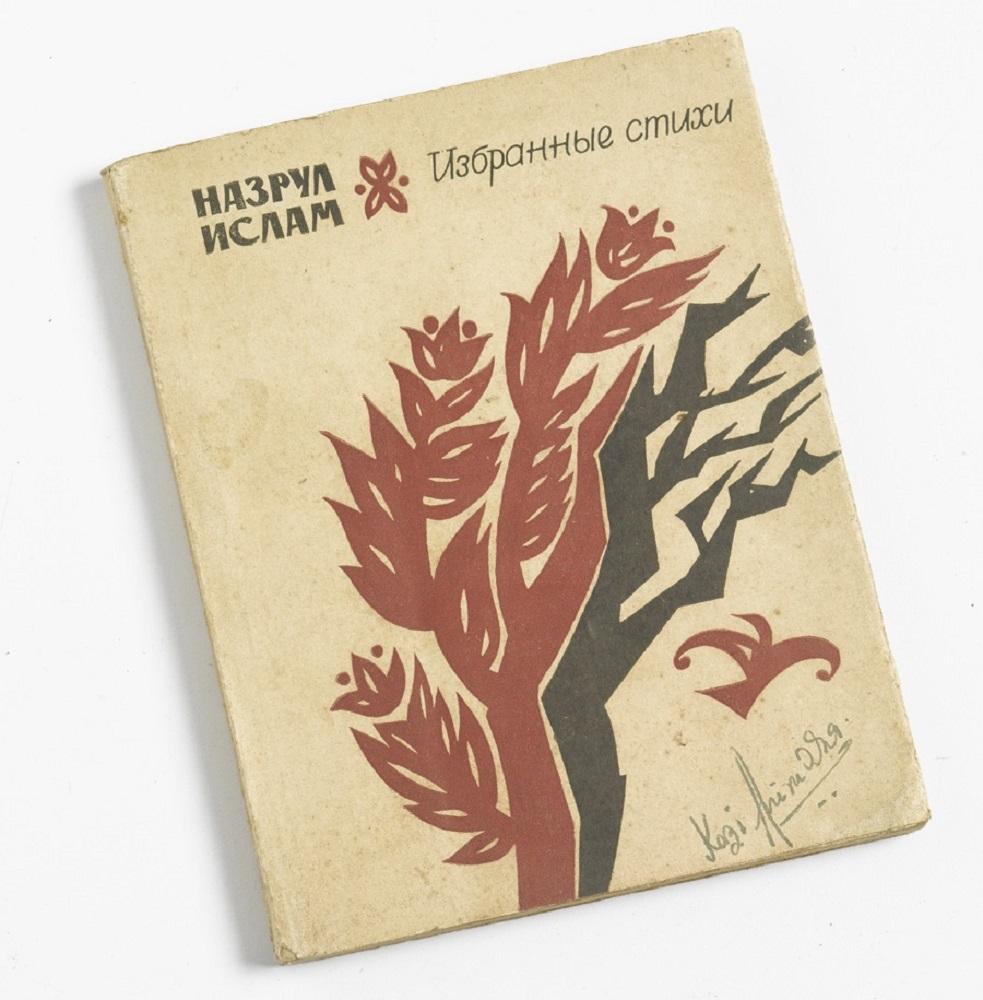

Vivek Das’ commercial work often involves photographing objects in his studio. This is from a series of books, personal items and letters belonging to Kazi Nazrul Islam. (In Nazrul, the Poet Remembered. By Kalyani Kazi. India: Wisdom Tree, 2009. Reproduced with permission of the author.)

The work of commercial photographers can provide access to discourses that are conventionally disregarded in critical and academic theories. It is especially so for those that attempt to activate political forms of image-making in direct conflict with the logics of mass production and easy reproducibility of creative work. This is part of the myth of the photographer’s artistic individuality that is supposed to rub off on the creative work—the photograph—making it, in turn, a unique object. Here, the critical, historicising voice of the singular, author-photographer usually provides the tools for reading the photograph or deconstructing its cultural, power-inflected accretions. In other accounts, the photograph is given some autonomy over the strict cultural conditions imposed by the photographer so that one may forge a new image of equal participation between the subject and the artist/ photographer. The relationship between the two, which one can triangulate to include the viewer of the photograph as well, is still marked with suspicion, rather than trust or belief.

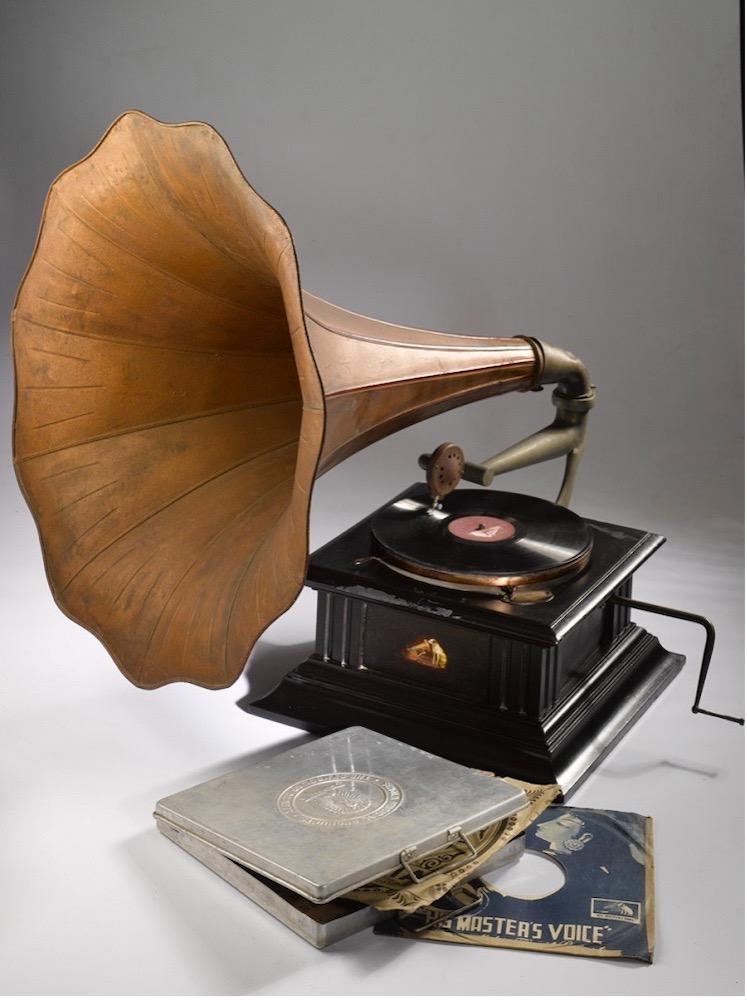

As part of his commercial archival work, Vivek Das uses his studio for shoots where he has to manipulate light and conditions to achieve documentary clarity. (In Nazrul, the Poet Remembered. By Kalyani Kazi. India: Wisdom Tree, 2009. Reproduced with permission of the author.)

A scholar like Paul Frosh would call these a part of academia’s “standard critique” where the commercial or stock photograph (usually a generic image which can be licensed or purchased for a fee) is a “bad object” of cultural production in a late capitalist society. A culture-debating society is encouraged to transform into one that simply consumes culture. Is there any escape from this totalising impulse of the culture industry? To think in the manner suggested by the “standard critique” is then to avoid other ways of accessing the new, contentious, publicly debated zones of pleasure that are being created in new media and digital cultures every day for ordinary users of cameras and other image technologies. As Frosh says, this critique:

“…fails to consider photography as an ambient or ‘absent-minded’ medium, an image-ecology (itself part of a broader multimedia ecology of visual and other technologies) bound up in a complex force-field of attention and distraction that moves across multiple images, and that speaks as much to existential and social generality as it does to the specificity of the real.”

So it is not the romantic, singular referent (or real)—whether imaged or conceptualised—that should necessarily attract our attention in discourses of critical photography but, equally, the consequences of its mass impact, circulation and the creation of new affective terrains for performance and visibility.

The formation of new public images depends on the articulation of such new generalities of being in the world—and the work of the mass produced photograph helps us trace the stages of this process of transformation.

A View of the Victoria Memorial. (Kolkata, 2000. Image courtesy of the artist.)

The work of a commercial photographer like Vivek Das—whom I spoke with early in February—shows us some of the polemical stakes involved in such critical discourses of photography in relation to its commercial and documentary aspects. Following a brief overview of his career he spoke about the images featured here, along with some of those “generalities” which guide his aesthetic vision in the digital era.

All images by Vivek Das.