On Absent-Minded Archives: Reading Photographs of Objects and Monuments

Based out of Kolkata, Vivek Das started taking photographs as early as the mid-1950s when he was a child, transitioning into the professional sphere as an advertising and commercial photographer in 1974. The most important change happened in the late 1990s when he adopted digital cameras and gave up the elaborate, resource-guzzling processes of developing and working with analogue film. He went to great lengths describing the long hours he spent lugging heavy equipment around on location shoots until late in the evening, followed by several labour-intensive hours in the dark room. Relying on inefficient infrastructures of water and electricity supply effectively implied that one had to give up on the possibility of professional, every day work. So, he invested in Uninterruptible Power Supply (UPS) systems and water softening machines that could keep his studio running through the usual breakdowns, at least until the late 1990s. There is no nostalgia for this period in his account. Nor is there any preference for a method that, as he saw it, hindered the kind of clarity and visibility offered by digitally informed images.

This was not always the case though. The move to digital was embraced around the time he started taking the photographs featured in the previous post and below. Presenting standard, commodified views of popular landmarks and monuments in Kolkata, these images speak toward the construction of such “absent-minded” archives or ecologies of circulation. The strong ambient thrum of their accumulated mass fix specific ways of creating depth, clarity and total visibility, albeit from a partial or limited-range. They emphasise the singularity of their presence, but also their detachability, worthy of packaging in a travel brochure or calendar—which was the occasion for shooting the photograph of the bridge—while claiming access to the authority wielded by the material (including virtual) presence of a range of multiple, similar images at the same time.

A View of the Vidyasagar Setu. (Kolkata, 1999/2000. Image courtesy of the artist.)

Significantly enough, Das pointed out the range of unique factors and permutations that allowed him to capture the photograph of the Vidyasagar Setu (or the Second Hooghly Bridge, finished in 1992) around the year 2000. These are the “coincidences” that fix temporal and spatial coordinates into the imagined narrative of a nationalist, mass-produced aesthetic; the performance of the photographer, reflecting “…the unselfconscious exercise of abstract thought.” He spent a few hours looking for the right combination of factors that could give him the right image. The boats, which floated into his ken towards sunset, provided him with “anchor points” that marked the depth of the image. These created a field of linear progression so that the discrete objects in the photograph—the water, the bridge, a trace of the city’s skyline in the distance—appear lined up by the vision of the photographer. The evening presented another opportunity to install artificial light within the image as the bridge is illuminated for public viewing. According to him, it gave the image the necessary burnish and brightness. He rued the lack of detail in the patch of ground that marks the riverbank and attributed it to the infancy of digital technology at the time.

With the proliferation of new software and technologies that can unravel greater layers of detail and information in the digital image, Das embraces the promise of clarity. He recommended the use of both Lightroom and Photoshop, considering them to be complementary tools that can help him achieve the desired image for his clients. His photograph of the Victoria Memorial emphasises the citizen photographer’s rights of total visual access to the monument. He told me how he avoided a screen of trees that obscures it partially from a different angle and worked out a method to include the illumination of sunshine without any hard shadows intruding into the foreground. It is remarkable for its strident opposition to the romantic economies of ruin porn, for instance. Through careful acts of vertical-line manipulation, he achieved the effect of this spontaneous but endlessly repeatable image.

As most pedagogical tools online—see pixpa, for instance—would confirm, establishing an easy, repeatable method to produce the clearest images is one of the important signifiers of value for the commercial photographer. Das reckons that while the analogue image was largely fixed upon the pressing of the shutter; with digital technologies today, that process of fixing the image actually starts with the pressing of the shutter.

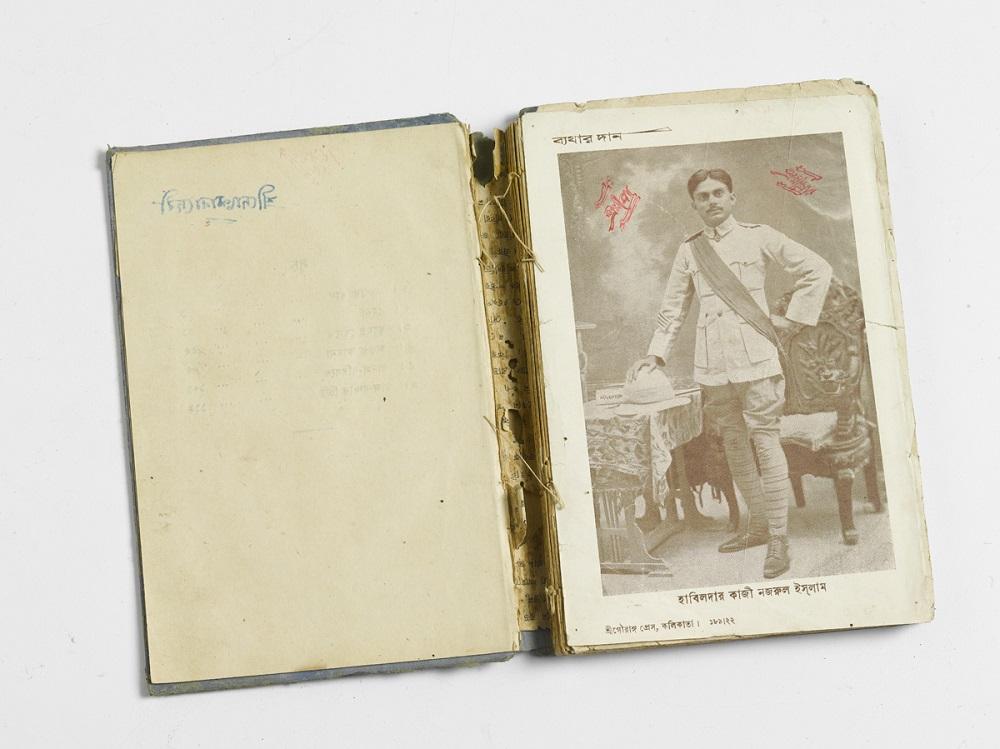

"Clarity" of the image is also aided by the object’s careful removal from any trace of background information. The flatness helps to attach the object as unambiguously as possible to its textual description. (In Nazrul, the Poet Remembered. By Kalyani Kazi. India: Wisdom Tree, 2009. Reproduced with permission of the author.)

He still retains the use of a studio though. For the other, important part of the job requires him to shoot flat pictures of objects, with controlled lighting and manipulated shadows. He has worked on a range of books that use photographs of old records, manuscripts, pictures and letters, documenting each of these objects separately for the reader’s access. The idea of clarity asserts multiple functions—from aesthetic to documentary ones—which fall under the remit of his every day process.

The range of his work—instead of offering a limited critique of the “bad” cultural object, the commercial photograph—involves several ways of diffusing the essential identity of photographic images. This includes emphasising its protean possibilities for adopting and embodying forms of pleasurable recognition, while embracing the risk of dissolving its “individual” identity into an abstract ambience or community of identifiable, almost inter-changeable, images. It is the submission to this risk, in fact, and becoming an “agent of similarity” (Prosh) that provides a warm confirmation of pleasure in seeing and being seen—publicly and multiply.

Instead of offering a limited critique of a "bad" cultural object, the commercial photograph shows us different ways of diffusing the essential identity of photographic images—emphasising its protean possibilities for adopting and embodying forms of pleasurable recognition by a community of image-makers. (In Nazrul, the Poet Remembered. By Kalyani Kazi. India: Wisdom Tree, 2009. Reproduced with permission of the author.)

All images by Vivek Das.