Resolution, Information and Memes: In Defence of the Poor Image

Hito Steyerl, a German filmmaker, moving image artist and theorist, has written extensively about the dissemination of media artefacts in the contemporary technological landscape. The Wretched of the Screen is a collection of her essays on the politics of images. In one such essay from the book, Steyerl unravels the politics embedded within the structure of digital media, theorising around the reproduced and circulated low quality or “poor” digital images.

In the course of the essay, she overlays the ideas of richness and poorness onto high resolution and low resolution media formats respectively, on account of the structural systems required for their production, upkeep and distribution. In doing so, she replaces the emphasis on “quality” as an inherent value within images and sheds light on the socio-economic systems required to produce this quality or lack thereof. On today’s image sharing platforms, the economy of memes—text and image commentaries—function in accordance with Steyerl’s ideas about the poor image. The more they are shared (through screenshots and unofficial downloads), the more the resolution of the image decreases. This also becomes a metric visible through the same pixelation, giving rise to a whole sub-genre of “deep fried memes” which are marked by the (often fabricated) presence of noise and static in the image.

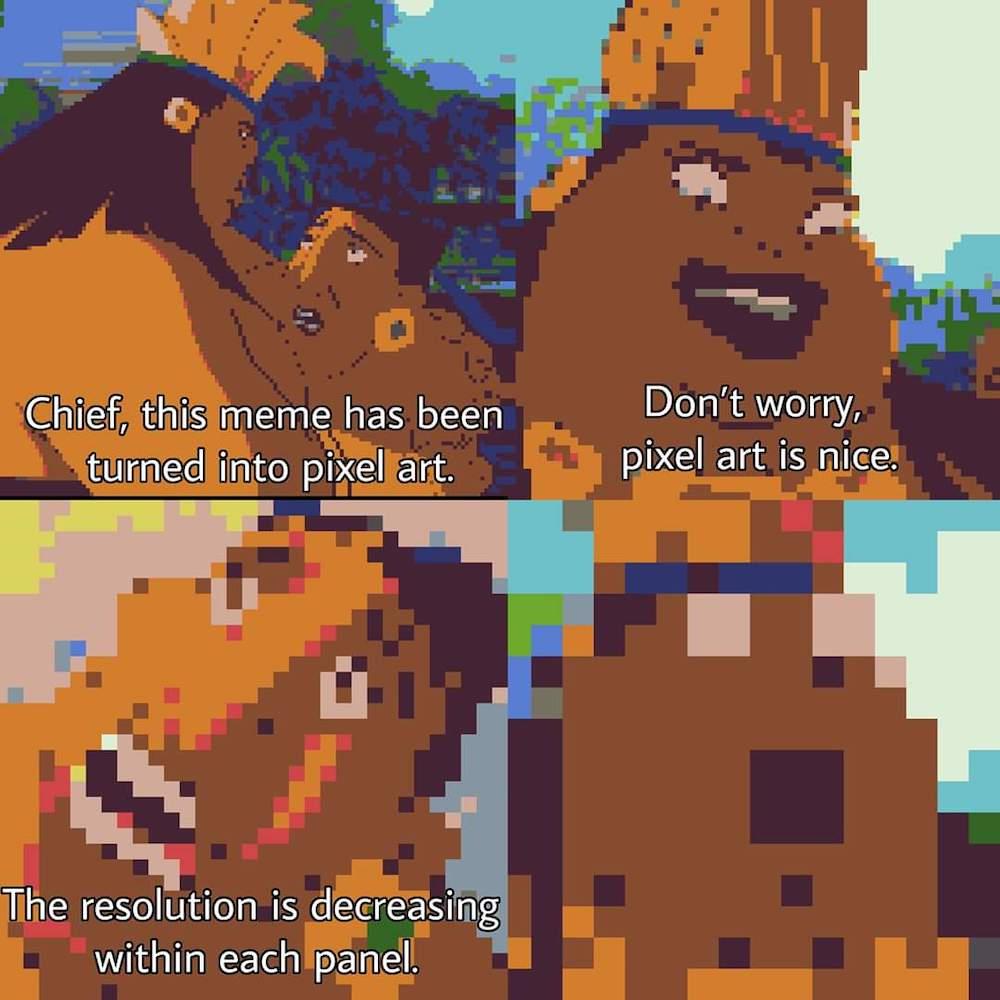

Made in a popular four frame format referencing a scene from the animated film The Road to El Dorado (2000), this meme creates a self-referential loop in which the image successively loses its resolution in each frame. In the original scene, chief Tannabok initially dismisses the news he is given, only to later realise its larger implications. The same tension persists in this image about pixelation which threatens to break the semiotic functions and boundaries of the image. (Meme posted by u/oluvshfrick on Reddit.com.)

“The networks in which poor images circulate thus constitute both a platform for a fragile new common interest and a battleground for commercial and national agendas. They contain experimental and artistic material, but also incredible amounts of porn and paranoia. While the territory of poor images allows access to excluded imagery, it is also permeated by the most advanced commodification techniques. While it enables the users’ active participation in the creation and distribution of content, it also drafts them into production. Users become the editors, critics, translators, and (co-)authors of poor images.

The circulation of low quality images of world events within the economy of memes becomes a potent surface for critical commentary by various stakeholders. Photographs of the Japanese container ship “Ever Given” which was stuck in the Suez Canal for over six days became the subject of a large number of memes, often critiquing the contexts of global capitalism within which this blocking of the Suez Canal was being discussed. (Left: Image from @diseconomemes on Instagram. Right: Image from @billikidharhai on Instagram.)

Poor images are thus popular images—images that can be made and seen by the many. They express all the contradictions of the contemporary crowd: its opportunism, narcissism, desire for autonomy and creation, its inability to focus or make up its mind, its constant readiness for transgression and simultaneous submission. Altogether, poor images present a snapshot of the affective condition of the crowd, its neurosis, paranoia, and fear, as well as its craving for intensity, fun, and distraction. The condition of the images speaks not only of countless transfers and reformattings, but also of the countless people who cared enough about them to convert them over and over again, to add subtitles, reedit, or upload them.

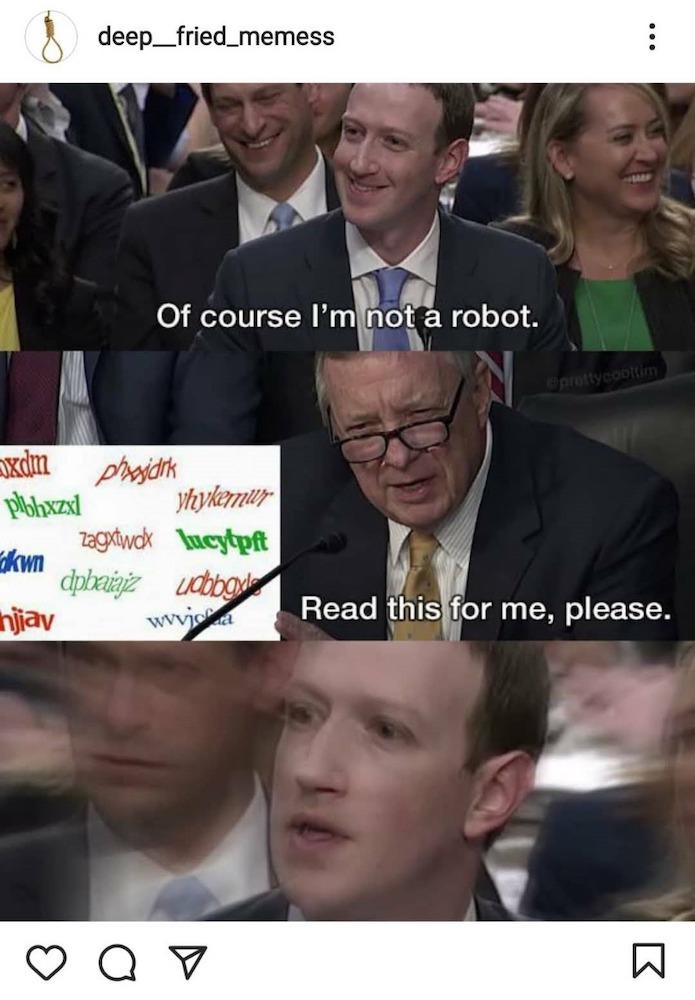

This image, taken from the Instagram account deep_fried_memess, refers to the court hearings in 2018, when Facebook’s Chief Executive Officer (CEO) Mark Zuckerberg had to testify after collective outrage about Facebook’s involvement in the outcome of the United States of America’s elections and other privacy breaches. Low-resolution images of Zuckerberg from news coverage of the event circulated as memes which questioned his humanity and constructed conspiracy theories around him being an ancient lizard or robot. These images, taken out of context and “deep fried” as memes, made narratives out of the noise and details in the image, expressing a public sentiment towards a figure of centralised authority. (Image from @deep_fried_memess on Instagram.)

In this light, perhaps one has to redefine the value of the image, or, more precisely, to create a new perspective for it. Apart from resolution and exchange value, one might imagine another form of value defined by velocity, intensity, and spread. Poor images are poor because they are heavily compressed and travel quickly. They lose matter and gain speed. But they also express a condition of dematerialization, shared not only with the legacy of conceptual art but above all with contemporary modes of semiotic production. Capital’s semiotic turn, as described by Felix Guattari, plays in favor of the creation and dissemination of compressed and flexible data packages that can be integrated into ever-newer combinations and sequences.”

First published on e-flux, click here to read more.