On a People's History: Suchitra Vijayan Discusses Midnight's Borders

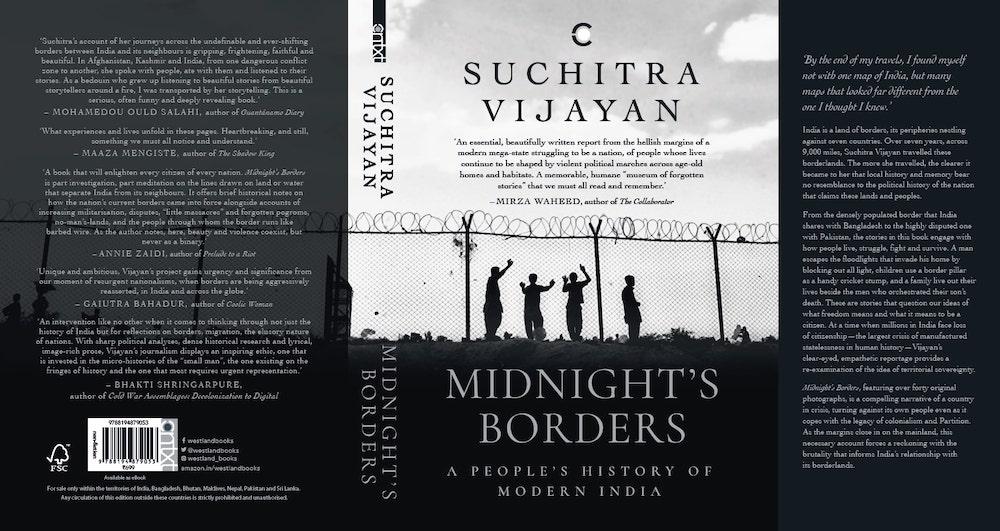

Lawyer, photographer and political analyst Suchitra Vijayan’s new publication Midnight’s Borders came out of her travels across 9000 miles of India’s borderlands over seven years.

Vijayan’s writing of this complex history shows the remorseless implications India’s policies have always had on the communities living in shifting borderlands. In an age of majoritarian triumphalism, sectarian violence and political polarisation; these implications are starker. In an interview with Senjuti Mukherjee, she discusses citizenship, belonging, the violence inherent in state policies, the ethics of seeing as a photographer, and more.

Senjuti Mukherjee (SM): In an attempt to understand and investigate the modern Indian state—or what you call a “Geopolitical myth,” in your introduction to Midnight’s Borders—you travelled across the densely populated, sometimes porous, and often contentious borders India shares with Bangladesh, China and Myanmar. What prompted such an urge to explore local histories in these regions?

Suchitra Vijayan (SV): We live in the age of big data, big histories, grand strategies and narratives. Everything seems to have exploded in size and scale. The phrase that comes to mind is from Mark Twain’s Gilded Age where he describes Miss Alice “…who is always trying to build a house by beginning at the top.” This is true of how we tell stories, write history and also make sense of our social worlds. (Of course, there are notable exceptions.)

I felt like we no longer asked “…large questions in small places." Understanding local history and memory became the framework most suited to the questions I had. Some people write from a place of knowledge, I have always written and photographed to understand my reality. I was trying to think through grand ideas—freedom, citizenship and belonging—that no longer made sense to me. The challenge was to excavate the past—anchored in the present—and more importantly, test the possibilities for change. First, what do we do with the remnants of the past—as objects and stories that do not sit comfortably with the myths and fictions in place? Second, can we rethink, remake and rebuild a better world?

SM: Towards the end of your multidimensional investigations came the Citizenship (Amendment) Act in 2019, manufacturing the largest crisis of statelessness in recent history. It poses the impossible challenge of producing evidentiary documents, the lack of which will strip citizenship from millions of people—especially those living in the borderlands. Have you since been in touch with any of the people that you spoke to during the course of your work? How have circumstances changed?

SV: Two people who appear in the book passed away, and one person disappeared. Some have fled their homes in fear. In one instance, the phone went dead, and later it was reassigned. When the first manuscript was close to ready, I had to pull three or four stories of people who chose not to have their conversations published. Some were affected by National Register of Citizens (NRC); others genuinely feared having their stories documented.

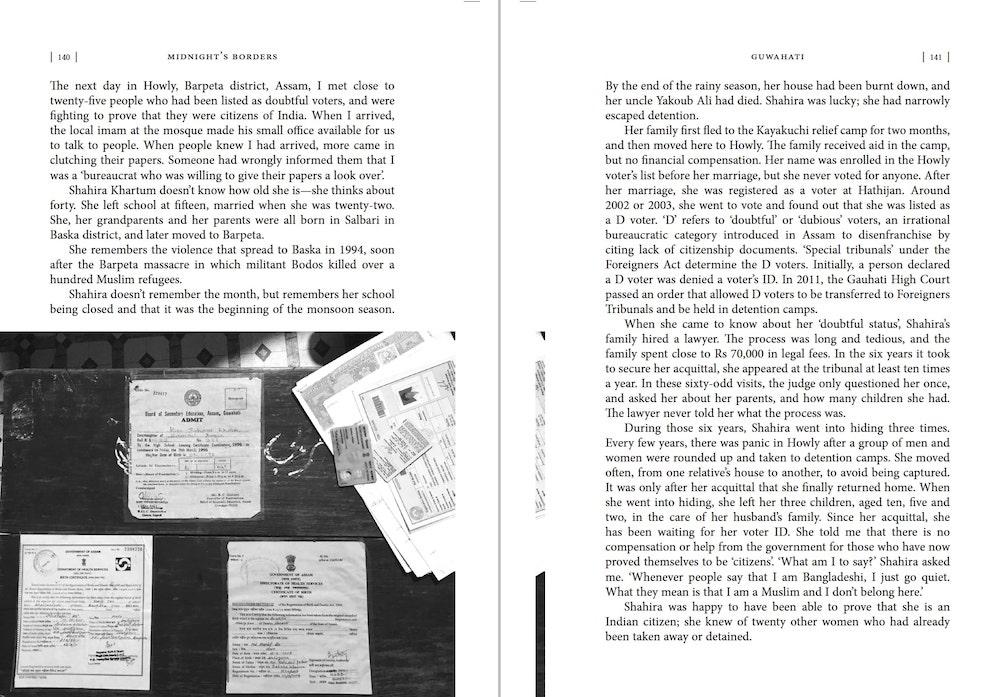

Demanding that people provide citations for their lived history is an act of violence. It is not just a question of stripping citizenship—that is one aspect. It is also ascribing value based on the capacity to collect, hold and reproduce evidence of your existence.

SM: There is an archival instinct underlying your work through the use of forms like oral history and visual storytelling. How important is the exploration and documentation of such histories that call into question state narratives and shift power to the people? Do these forms risk erasure and irrelevancy within the contemporary publishing and archiving worlds?

SV: The idea of the archive begins with the “State.” No other institution has invested in the function of creating, telling, circulating and controlling stories. Not all documents arrive at the archive. Archives have rules and categories of “achievability” that dictate what will be preserved, studied, kept alive and by whom. Membe writes about this, and characterises the archive as a cemetery: “…fragments of lives and pieces of time... interred.” So, if we start with that idea, then the real work of excavating the unarchived happens elsewhere.

I have always had an uncomfortable relationship with the archive. In the book, I refer to these narratives as a museum of forgotten stories, accounts and objects. My work starts with those violently erased from the archive, or buried as footnotes, yet still find ways to preserve their maps and memories.

In Kashmir, for instance, I encountered people who remade newspaper photographs into family albums and scrapbooks. Many Kashmiris during the height of the insurgency destroyed family albums and pictures. When I reviewed Sanjay Kak’s book Witness, I encountered something similar: Syed Shahriyar made a scrapbook with hundreds of clippings from local papers. In the book, he says he took his album as a sign. The next day, armed with a camera, he headed to photograph the Friday prayers followed by protests. These photographs are not part of the archive, but they are part of collective memory. What place do these scrap books, images and photographs occupy?

SM: This is an excerpt from your chapter on Panitar, one of the 250 hamlets that extend across India’s border with Bangladesh:

“The day, standing just a few feet from where Nurul Islam lost his child, I saw two children running around and playing with an orange-and-purple kite. I picked up my camera to take a picture, but Ali requested that I don't... Here, lullabies and bedtime stories are cautionary tales of how to not stray too close to the border fences. Their images don't need to become a part of an archive of violence... I apologised immediately, and watched the children chase the kites."

Earlier in the book, you mentioned that you were in the process of rethinking your photographic practice and the possibility of images to become “archives of memory” instead of “documents of truth.” As photographers’ ethics of seeing are ingrained in their practice, what are the challenges in using this medium constructively to reinvestigate and subvert mainstream narratives?

SV: For far too long, we photographers have cast ourselves in the role of a “witness” or an “objective bystander.” We are social beings irrevocably bound by the complexities and messiness of being human. We are political beings afflicted by our privileges and prejudices. The instinct to always shoot first and capture a moment is something I had to unlearn. All moments do not have to be captured. Letting go of the story—to not photograph—is also part of being a photographer.

Second, it's almost impossible to subvert the “mainstream” because almost all work is now created for consumption and acquired by an institution, museum or a marketplace. This places specific demands on the photographer. The image then is not a reflection of the political or social moment, but a response to what will be bought, sold or rewarded. This is why visually arresting Kashmir images can appear in Mumbai's lifestyle brand stores exhibited along with mimosa brunches, devoid of politics. Or images of rape can make their way to jury prizes and awards without ethical considerations.

SM: In a series of talks hosted by the Chennai Photo Biennale starting today, you will be rethinking questions of ethics, power, representation, and the relationship between photographers and the social worlds they document. Do tell us a little bit about this programme and the photographers you will be in conversation with.

SV: I am an autodidact. I taught myself to write and take pictures. As I started making images, I began asking questions about power and representation, process and practice. I did not know what to call it back then. I remember spending hours reading images, trying to learn composition, or in some cases, replicate what was ordained as a great image or image-making practice. I quickly discovered that the capacity to take visually stunning photos did not correlate with being ethical or having even a basic understanding of power relationships. A part of this learning/ unlearning was through conversations with people struggling with or trying to make sense of this.

When the Chennai Photo Biennale reached out to me to host a conversation, it quickly evolved into a series. The book became a point of departure to think through these questions with others. Photographer and author Ritesh Uttamchandani is a friend, and we have had these conversations since 2007/2008. I have read and learned from political geographer Sinthujan Varatharajah’s work, they draw crucial parallels between various acts of displacements, policing and violence. Similarly, I have followed Laura Saunders’ photographic and film work on United States of America/ Mexico borderlands closely. She is also thinking through the relationship between dissent and the carceral system. I met photographer and educator Rishi Singhal last year, and I am curious to learn more about how these questions play out in educational spaces, how to understand who and what is being taught.

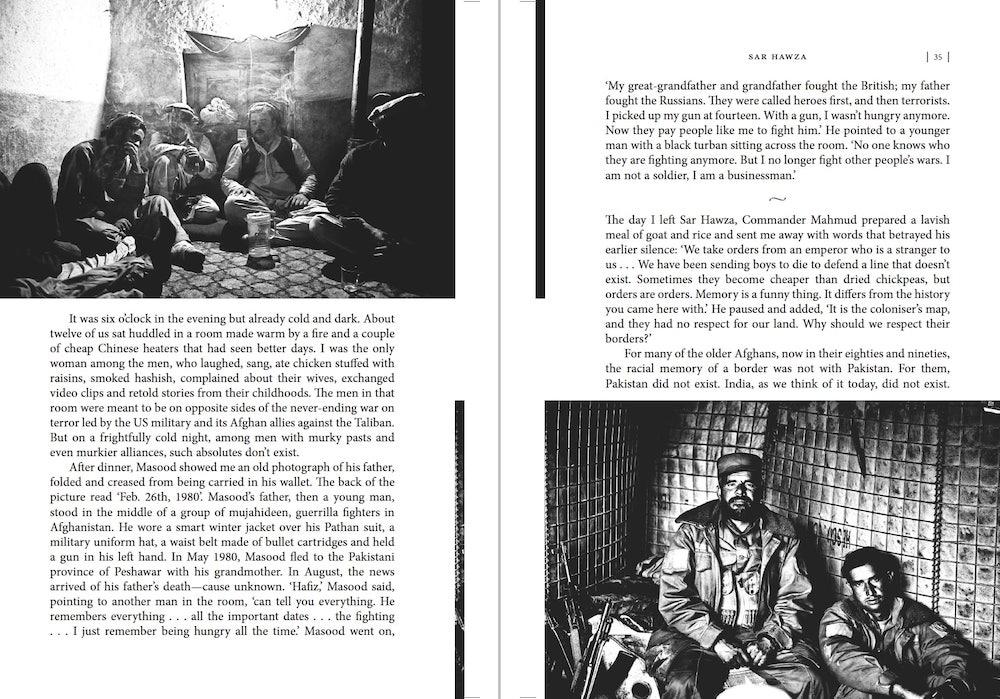

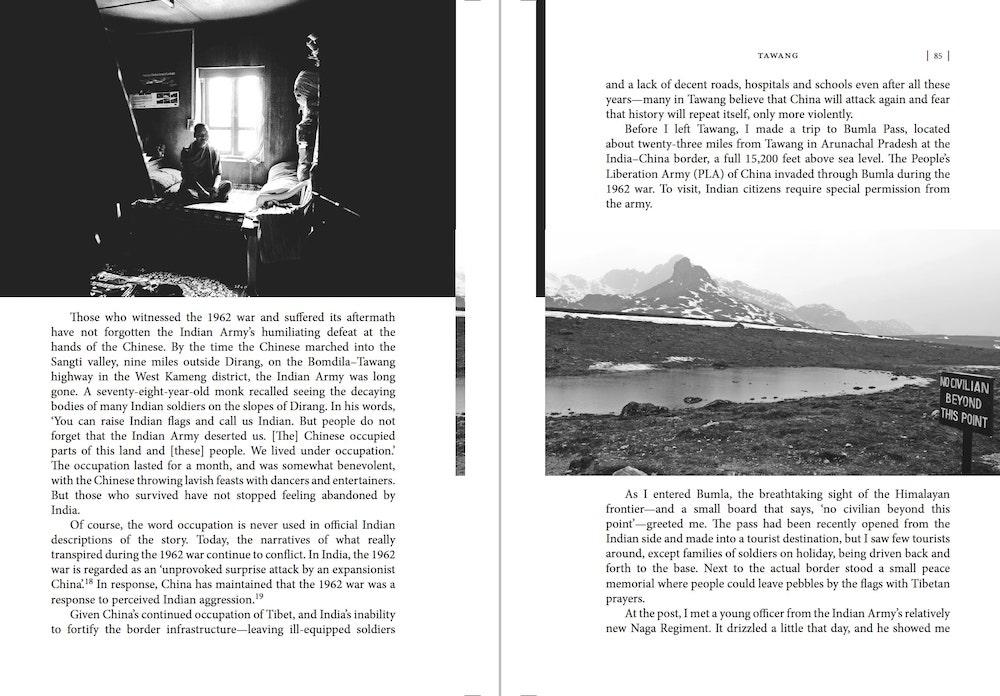

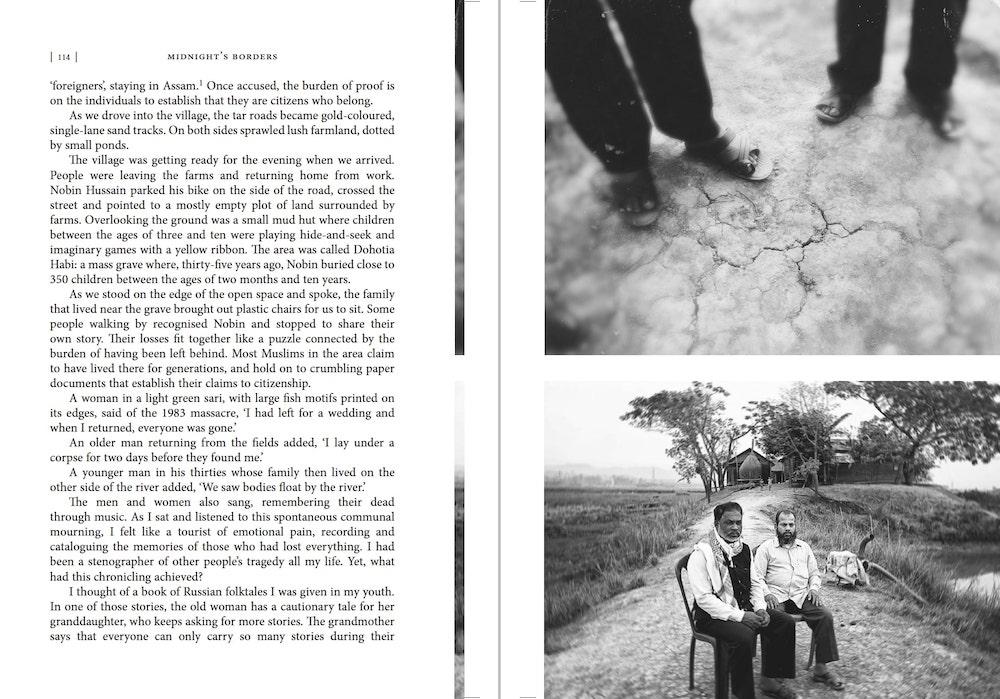

All images from Midnight's Borders: A People's History of Modern India by Suchitra Vijayan. India: Context, 2021.