From Landmass to Ocean: Conversations with Sinthujan Varatharajah

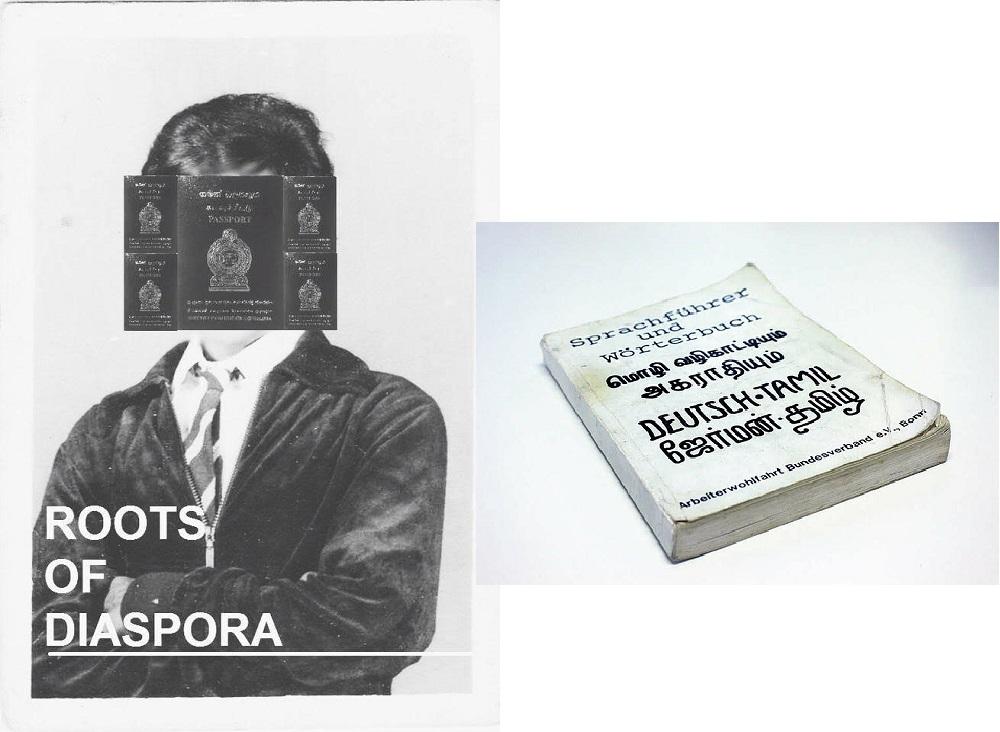

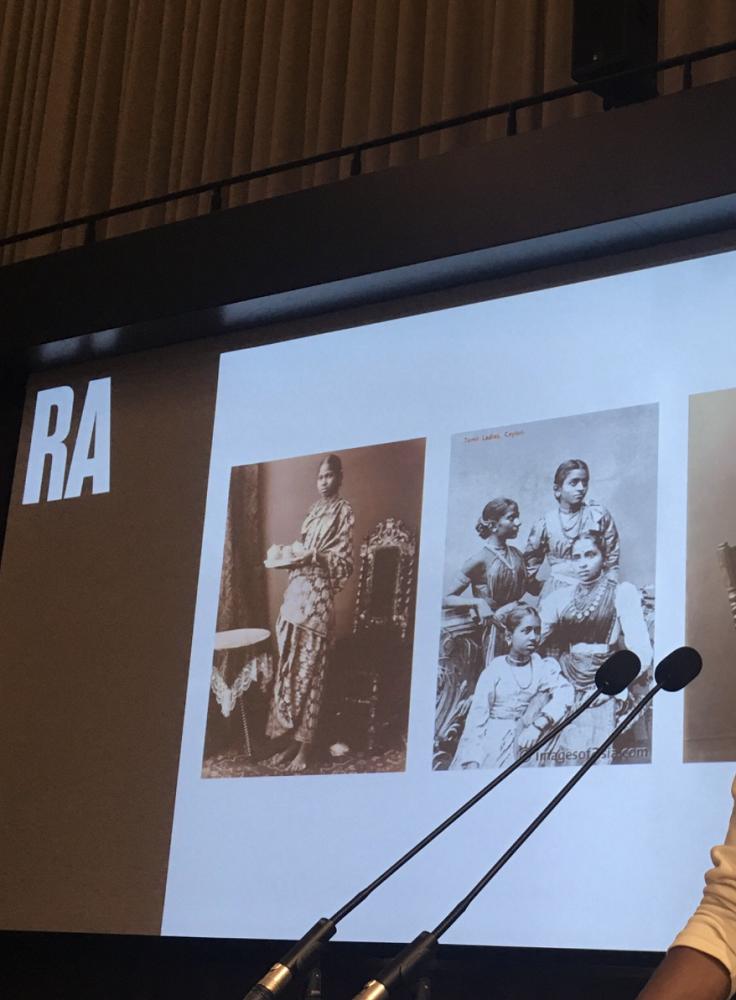

For political geographer and essayist, Sinthujan Varatharajah, the most important task is to reverse the “curated invisibilities”—practised by nationalist governments—that prevent the formation of a cohesive and visible source of identity for exiled communities like the Eelam Tamil community. Language forms the other kind of resource that helps them find a common ground of experience and narrative. (Left: Roots of Diaspora #011 Senan. [Sinthujan Varatharajah. December 2013.] Right: German–Tamil Phrasebook and Dictionary, published 1989. [Photograph by Sinthujan Varatharajah. Germany, 2020.])

As part of the Chennai Photo Biennale’s series of conversations reflecting on practices of representation, Suchitra Vijayan spoke to the Berlin-based political geographer and researcher, Sinthujan Varatharajah on 15 April 2021. The conversation flowed across the specific nature of their projects—broadly, on visualising zones of political distinction—to settle into a space where dialogue could take place, difficult questions tackled and personal methods held up for scrutiny. Varatharajah emphasised the centrality of their own Eelam Tamil experience in their work. Having been brought into Germany in their childhood as a refugee—with their parents escaping the ethnic cleansing in Sri Lanka during the late 1980s—the exiled, Eelam Tamil community remains the first, imagined audience for all of Varatharajah’s work.

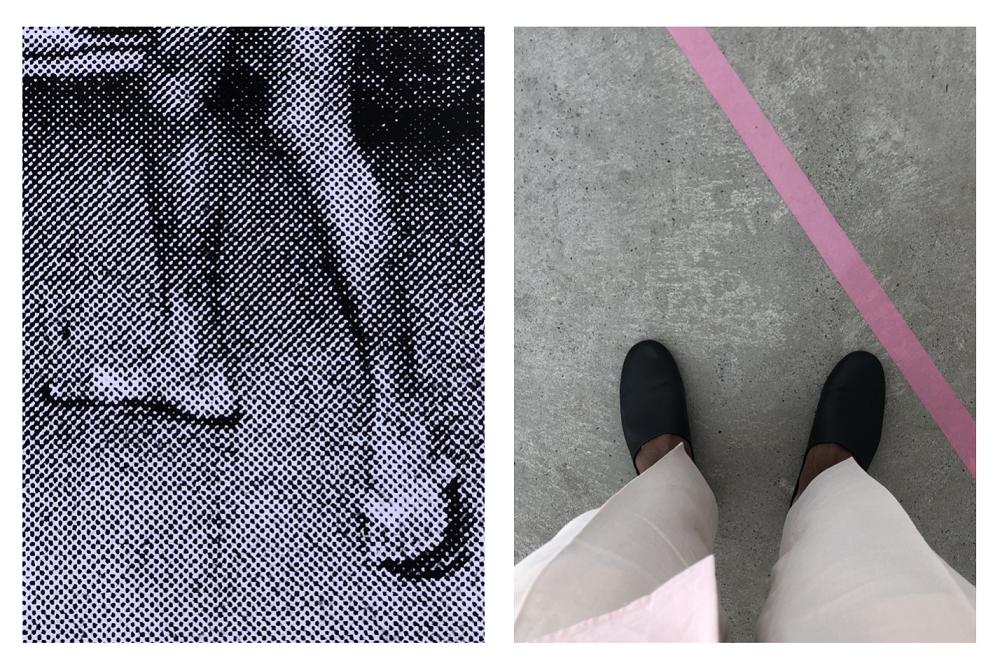

Traumatic histories of violently dislocated communities produce fault lines that get enjoined to the public memories of host countries—much as the diverse refugee populations would have confronted the momentous upheavals of Germany on the verge of the collapse of the Berlin Wall. This informed one of Varatharajah’s artistic projects too—where they used the maps of Berlin to recreate the lines of movement that were adopted by Eelam Tamil refugees negotiating the space of Berlin in the late ’80s. This translates as an act of reclamation—whereby the city of Berlin becomes reconstituted by the imaginative investments of the Eelam Tamil populations that have passed through it.

Varatharajah’s practice questions the easy elisions by which airports become transformed into border zones, demanding visas and passports from people often trying to escape the violence of their land. Their work concentrates on recovering the traces left by the imagination of such paranoid, distinctive borders on the actual bodies and memories of refugees. (Installation View of Model of Russian Aeroflot Iluyshin IL-62 at Berlin Biennale. [Photograph by Mathias Vötzke. Germany, 2020.])

Varatharajah discussed how images, texts and objects—digitally produced or otherwise—occupy the multiple ways in which such repressed histories of reclamation can be recreated and given new modes of visibility. The exilic diaspora is condemned to return to Eelam only through acts of imaginative and virtual arrival. Negotiating the difficult, increasingly censured spaces online—and helping others do so—is another important facet of their political activist work. Varatharajah's work rejects the visual regimes constructed by the restrictive, legally and spatially bound, inter-sectional gazes of white Europe, nationalist India and (majoritarian, Sinhalese) Sri Lanka that seeks to overwhelm the subordinate links between two Tamil communities separated by an unruly strip of water. Varatharajah almost attributes this fluvial, oceanic border zone as a utopic space on which a possible map of belonging for the Eelam Tamil communities across the world can be drawn. Unpicking the “curated invisibilities” that afflict the fates of refugee populations across the world linked by their common traumatic experiences—whether Tamil, Palestinian or Ghanian—remains a guiding principle for the artistic and research methods chosen by Varatharajah.

Since their work is primarily exhibited in Germany—where they live and were raised—Varatharajah emphasises the role of translatability. They believe that it can allow dialogue to take place between the political languages of European activism and non-Eurocentric discourses of belonging and participating in the political struggles of Europe. As each increasingly seep into the discourses of the other, a utopic community of the future—detached from considerations of geopolitical reality—may emerge.

Varatharajah later spoke to Ankan Kazi to burrow deeper into some of the themes raised by their conversation with Suchitra Vijayan.

Ankan Kazi (AK): The concept of oceanic borders that you discussed was very fascinating. Especially for exilic communities from island states: one gets the sense of being surrounded by a world of fluvial, shifting, subtle, but clear zones of distinction. How do you visualise these conceptual movements while working with online spaces—do critical acts of “surfing” help change the terms of what becomes visible outside the nationalist gaze of, say, India and Sri Lanka?

Sinthujan Varatharajah (SV): In my work I try to uncentre land: mentally, emotionally, rhetorically but also visually. I try to reframe, redraw and tear apart maps, to draw attention to how we privilege land over water; to how we measure distance not by matter (of) how far a place is, but by matter of how nation states have drawn boundaries and built infrastructure to reinforce these boundaries, proximities and distances. Through my work, I want to understand what it means to look at each from different shores of the same ocean, to not think of us as people of a landmass, but people of a sea. I try to enquire how that conceptual difference helps us understand our place in this world better; how to envision a future which allows (one) to exist differently than today.

Varatharajah emphasises the impossibility of reducing history to singular gazes—whether national or global. To reverse these oppressive terms of visibility for refugee communities, they frequently work through the premise of envisioning cities like Berlin as also a Tamil city, using maps and lines to chart the movements of Eelam Tamil Berliners through the city.

AK: Considering the multiple media you use for your work—how do photographs feature in your scheme of things? Do they serve any specific associations with your memories of exile or in the shaping of identity? Do you use only personal photographs or do you find/ source them from Eelam Tamil refugee communities? Since they are always the first imagined audience for all your work, what kind of ethical considerations enter your practice of using personal images for public exhibits?

SV: I use photographs in my work as a form of documentation and testimony. In the context of a mass displacement, material manifestations of a past are often the first to be lost. This rupture—this lack of visual memories—has a toll on people's sense of self and their personal as well as collective histories. Therefore, I use a lot of personal photographs—old ones and new ones—to counter the absence of such material memories, create a new visual language and landscape and therefore stabilise the sense of exiled, displaced-self. I also tried to create a digital archive of portrait photos taken in Eelam by tapping into Eelam Tamil community networks. I have used some of these in my work. However, over time, I shifted to using more abstract photos and imageries to narrate stories of exile, moving away from bodies to landscapes and built structures. Using people's photos, displaying their bodies requires a lot of ethical considerations, particularly in the context of criminalised histories. Consent is, of course, paramount here. But how do you, for instance, receive consent from the dead? You are eventually forced to ask for consent from close relatives. But even then, you are left to ponder whether that is adequate. I often end up blurring faces or using single body parts to abstract from a particular person.

Varatharajah uses personal photographs as well as those acquired online to construct his narratives of memory. As specific geographies yield specific experiences, photographs help them arrive closer to the texture of their experiences— even if they have to abstract some of the details of faces, names and bodies.

All images courtesy of Sinthujan Varatharajah.

To read about the previous conversations in this series, please click here.