The Role of Storytelling in Photography: Conversations with Ritesh Uttamchandani

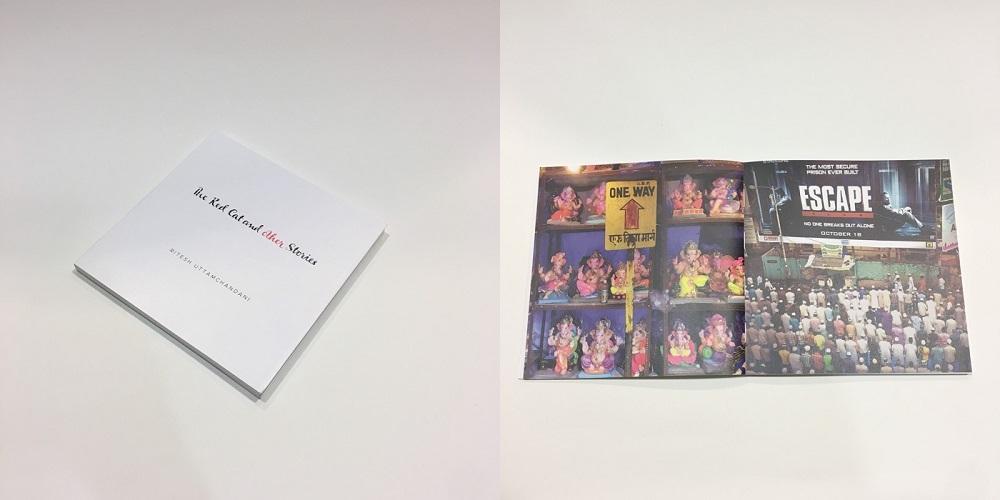

Ritesh Uttamchandani’s photobook The Red Cat and Other Stories relies on the spontaneous method of the snapshot—allowing for surreal juxtapositions on the centre spread and creating an eccentric map for a city rambler. (Image courtesy of the artist.)

The Chennai Photo Biennale hosted a searching conversation between Suchitra Vijayan and Ritesh Uttamchandani. Both were activated by each other’s work and sought to create a web of dialogue, references and provocative questions around their practice, ethics and politics—not just of representation, but of being, recording, speaking and negotiating the complex intersections of their own locations in space and identity while dealing with others. Vijayan’s book Midnight’s Borders invited a reflection on the standard methods of (photo/) journalism in relation to stories of power and vulnerability: How does a journalist refrain from being a mere reporter of speech, stripped of context?

Vijayan's project took her along the laboriously manned and militarised borders (usually by Border Security Forces) of India that have encouraged exploitative relationships with the residents that live in such uncertain territory—sometimes shifting due to climatic changes or political upheavals determined by the languages of nationalism. Uttamchandani also emphasised the role of personal experiences for photographers who seek to complicate the events they are reporting on. Questions about justice are prefigured inevitably by discourses of belonging and nationalism—both echoing the work of institutions that seek to homogenise rather than respect difference. This is where, he claimed, the role of storytelling comes to the fore, as a method that encourages the voice of a participant instead of reproducing the biases of the journalist.

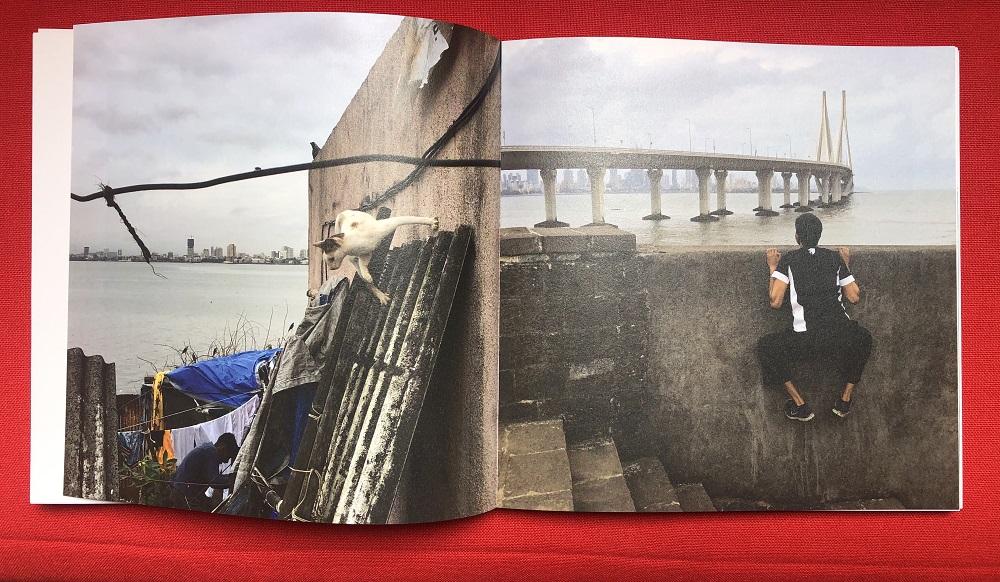

Uttamchandani’s images rely on the associations that viewers have of objects and forms substituting for dreams and narratives. These images emphasise the suggestions of continuity between the urban landscapes of a city like Mumbai and the dream-logic world of its residents, as sea-link bridges transform into protruding branches and humans adopt cat-like agility for survival. (Image courtesy of the artist.)

Uttamchandani was also taken up with the question of withholding or blocking—acts of not-telling—which worked as significantly as acts of accurate reporting, since one is dealing with the lives and narratives of vulnerable people under near-constant state surveillance. Vijayan agreed with the difficulty of wielding knowledge in charged spaces like borders. Trauma renders acts of memorialising rife with the possibility of revisiting violence and brutality. How do journalists work around this aspect of teasing out the memory of other people? As borders close in upon the possibilities for freedom and justice in the wider national imagination too, photographic and textual representations must increasingly confront the problems posed by visibility and surveillance, which seek to exploit and perpetuate the dangers of exceptionality. This confrontation can be made possible by looking toward eloquent modes of silence and translation that can activate the voice of the itinerant citizen-subject as a participant in their own stories.

.jpg)

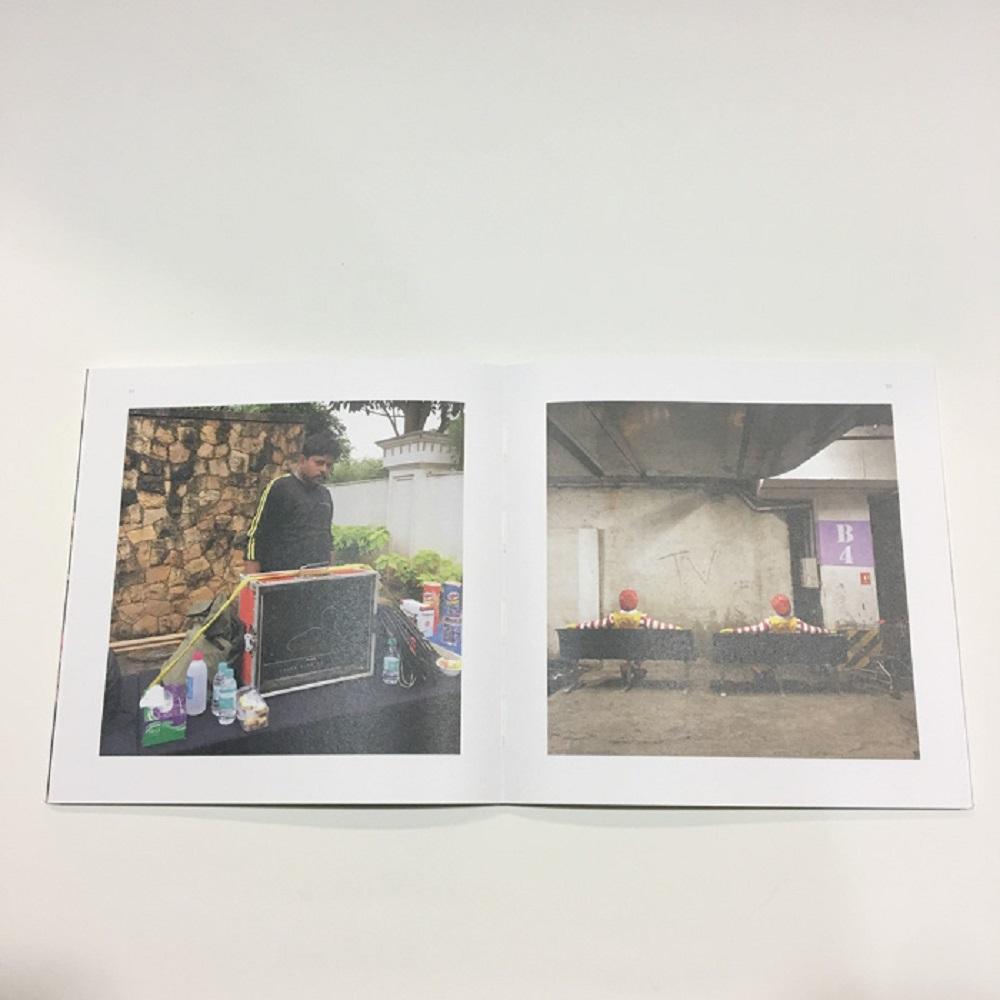

Uttamchandani’s book-making practice attempts to make the ordinary, popular spaces of his city more accessible to the ordinary reader and possible co-inhabitant of these spaces. Imaginatively, their investment in these spaces increases with their direct participation as readers as well as subjects. (Image courtesy of the artist.)

Ritesh Uttamchandani spoke to Ankan Kazi to take the conversation further, focusing on his own practice for The Red Cat and Other Stories—his first photobook on his home city, Mumbai. We asked him a few questions on his work: shifting from everyday photojournalism and working in an official newsroom to moving closer to the “art crowd,” as he put it, with his book-making, even as he tries to work toward democratising this space for the average reader.

Ankan Kazi (AK): Considering the interest Suchitra places on photographs to do another kind of work apart from mere representation, what kind of associations do you have in mind when you are creating your images? And how did you arrive at your project?

Ritesh Uttamchandani (RU): There was an increasing sense of being stifled by the dictates of newsroom journalism. With photojournalists, there is usually a strong expectation of what the image of an event—whether it is a war-zone or something more innocent—looks like and one is expected to mechanically reproduce that expectation. I was trying to move on from that and rediscover fresh ways of looking at images, especially of my own home city, Mumbai, which is regularly depicted through the usual clichés of cricket on the Maidan, Marine Drive, and so on. So, I wanted to get out of this space of the newsroom and try to document the everyday realities around me, which usually escape acts of memorialising—even if they do not quite escape the memories of someone like me who has grown up and lived here all my life.

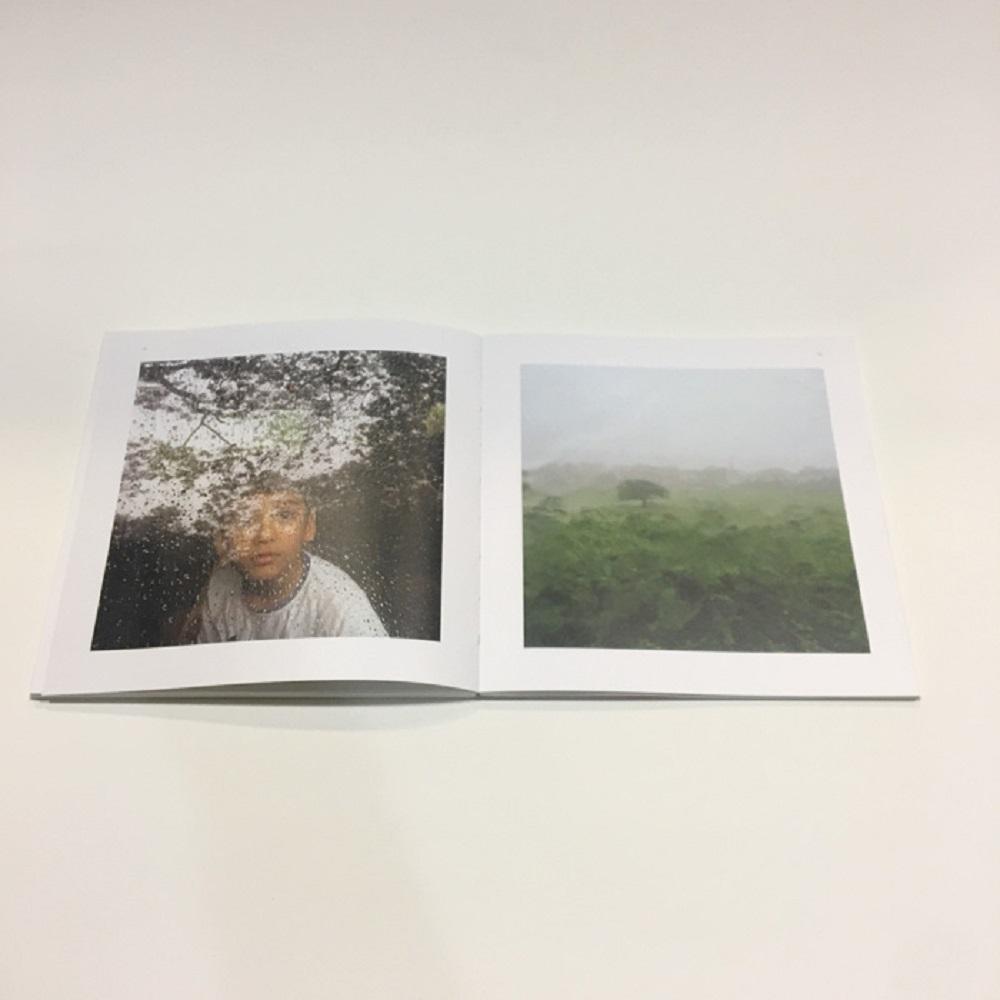

The surface of the image is a basis for sacred experience in Uttamchandani’s poetics of the ordinary. The potential for transformation, hybridity and spontaneity implied by these rich surfaces of reality inform his approach to landscapes and people. (Image courtesy of the artist.)

AK: Does the phone camera work better as a tool for accessing the ordinariness of space—locating its precarity and bringing out its sacred quality? How does it tie up with your post-production/ book-making methods?

RU: Once I decided to move away from the bulky cameras and equipment that were weighing me down on my usual news or photo assignments, I began to turn increasingly towards the possibilities offered by the phone camera. It allows for a quicker reaction time, so it rewards spontaneity. It also invited me to accept the loss of control over the final image as I do not have to worry too much about representing these scenes according to any pre-established norms of colouration, clarity or even meaning. These norms are in fact set in news or fashion offices internationally—as rules for representing specific skin tones on images etc. I wanted to avoid those and the nature of my project allowed me that freedom. I was just reacting to situations around me, it was that simple. There was very little post-production work done on these images (except for compensating for some colour loss, occasionally) after clicking them. My emphasis was on producing a book that was affordable, unlike the usual productions from the art world—which are bulky, expensive coffee table books that are inaccessible for most readers.

The photobook uses surreal elements to anchor this reality of the everyday into lived experiences of space and locality. Stories suggest the initial layer of context-building for the viewer, but images have the power to evade official records of memory and stick out inconveniently for narratives that look to explain a singular totality. (Image courtesy of the artist.)

All images from The Red Cat and Other Stories by Ritesh Uttamchandani. Hyderabad: Pragati Offset, 2018.