Advertising the Indian Real: Review of R. Srivatsan’s Conditions of Visibility

Srivatsan argues that advertisements and film hoardings often foregrounded an aesthetic tension between “individualized,” painted surfaces (which were mostly reliant on the cheap labour of sign and hoarding painters) and mechanical photographic processes of representation. Advertisements like this one—for a brand that sought to define the modern Indian consumer—reflect these anxieties.

Along with Christopher Pinney’s Camera Indica, R. Srivatsan’s book Conditions of Visibility (2000) was one of the early critical treatments of the cultures of pre-digital photography in India. Setting itself up at the crossroads of several transitions in Indian history, Srivatsan employs a semiotic method in these essays to map the contemporary styles of photographic imagery. He examines these in perpetual interface with the evolving significance of the public and the domestic spheres (functioning also as national spaces) in the imagination of postcolonial India. He seeks to engage the presence of the “illiterate” viewer as a “…utopic counter-figure of the subaltern” that can contest the normative figure of the Indian citizen, which, he claims, occupies a position that fulfills the binary between legible image and literate text.

Some of the transitions that frame these essays include the changes provoked by a Nehruvian modernity giving way to the populist energies released by economic liberalisation, the demolition of the Babri Masjid at Ayodhya and the anti-Mandal Commission agitations (against caste reservation in government jobs), setting off the early 1990s. This was also the last decade before digital photography offered different ways of rejuvenating the ground of the photographic image. Srivatsan focuses on the uses of photography as part of a developing discourse on image-making in a rapidly transforming India. He uses news photography and advertising imagery, especially, to drive his arguments home about the construction of new identities and desires for these newly forged spaces of visibility.

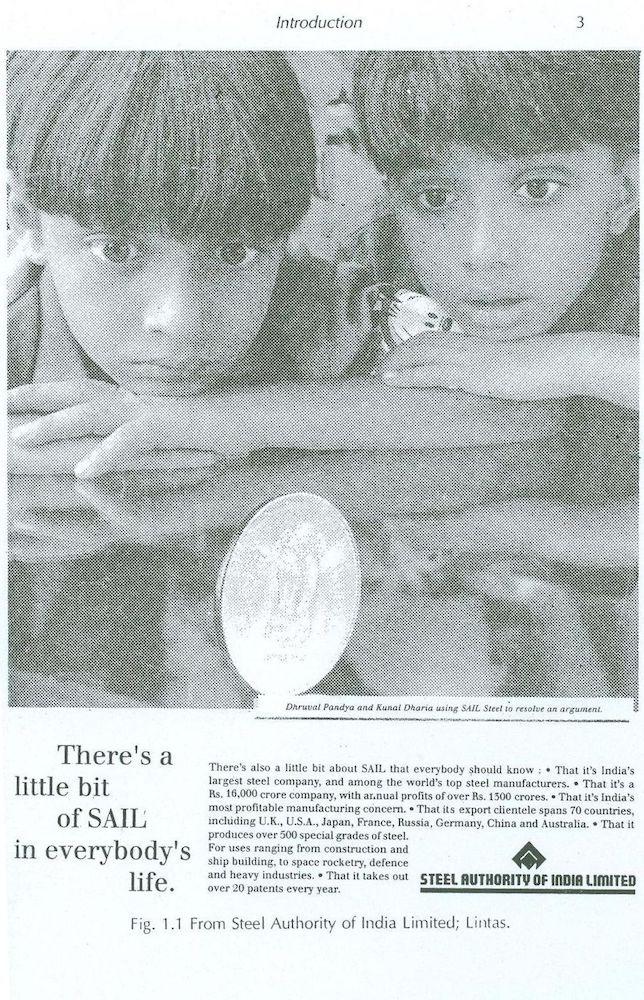

These arguments are set up by Srivatsan’s reading of an advertisement for Steel Authority of India Limited (SAIL)—one of India’s largest publicly-owned steel manufacturers—that uses interpellative text, image and space in allegories of significant narrative-making for the state of the nation at the turn of the ’90s. Enthusiasm for the future is carefully built upon an edifice of economic responsibility and class mobility. In the advertisement images, the contract between a public aspiration for the new Indian citizen and its basis in the structure of class, gender and caste hierarchies becomes visible. It is to Srivatsan’s credit that he seeks to explore the ways in which caste structures these regimes of visibility, although these explorations do not tend to go beyond formal investigations of this nature. He cites Kiran Nagarkar’s opinion that the new advertising discourse, using a mix of Hindi and English, aspires toward the “…new dominance of the English-speaking super caste” and usefully reminds us of the notorious Onida television advertisements of the early ’90s. These advertisements capitalised on the imagery of violence and lawlessness provoked by the Mandal Commission recommendations to pitch in their solidarity with the self-immolating protestors against the proposed reservation policies. Calling out a rare moment of unambiguous political imagery, he writes, “Clearly, there is such an overwhelming correlation between those who form the consumer base of a colour television and those who defend ‘merit’ that the Onida advertisement found it both safe and necessary to address this stratum of society in unambiguous political terms.”

Advertisements like these, Srivatsan points out, emphasise the basic unity of the family as a mode of consumption. The image of the woman—given an aura that extends to protect the family—is employed to forge this unity, even if it looks "overstressed."

Srivatsan’s idea of the political nature of news photography is also structured around violence. He takes the case of the riots provoked in other parts of India by the Babri Masjid demolition, by reading through the production of news images of communal violence in Hyderabad. Here, the newspaper forces a state of radical non-homogeneity onto the reader, compelling them to make sense of disparate events linked by the fact of their appearance on the same page of a daily newspaper. This forced juxtaposition and daily repetition allows the photographers of newspapers to, paradoxically, develop a signature of their own as they work through the matrices of institutional visibility and manipulate their own punctum (from Barthes) to affect the viewer. His reading of Barthes’ use of the term “punctum” may be questionable, but the thrust of his argument is clear enough. He provokes us to look for the conflicting as well as accommodative traces of state intervention; commercial allure; as well as secular, republican ideals being worked through these multiple, mass-shared images.

Srivatsan uses this advertisement for SAIL to outline his close-reading of the traces left on photographic advertisements that traverse public spheres inflected with private fantasies of inclusion, aspiration and class mobility—especially for the unlettered viewer. “The viewer,” he writes, “responding to the image, no longer says, ‘I recognize this as my own kind,’ but rather, ‘I recognize this as what is refused to me, and as what I will fight for.’”

To read more about Conditions of Visibility, please click here.

All images reproduced from Conditions of Visibility: Writings on Photography in Contemporary India by R. Srivatsan. Kolkata: Bhatkal and Sen, 2000. Images courtesy of the author and the publisher.