Conditions of Visibility: Reading R. Srivatsan’s Essays

Reading the images of women in advertisements, Srivatsan writes that they were frequently employed as “…an instrument of ‘modernization’… It is through the visual pleasure she provided that something which may be called ‘life-style’ was sought to be nurtured in the imagination of the viewer, opening it out onto the world of consumer products.”

The essays that make up the volume Conditions of Visibility (2000) form a set of related inquiries into the nature of contemporary image practices in complex inter-relationships with the growing consumer markets in India, state patronage and modernist aesthetics. R. Srivatsan’s essay on the use of the image in rowdy sheets, for instance, attempts to recover a stringent process by which ordinary blue-collar criminals are described by the state or the police report. Along with fingerprinting—which was another criminal investigative tool developed in colonial India—the photograph on the rowdy sheet gives us several continuities between colonial and postcolonial modes of defining and ascribing criminality (and citizenship) with the help of text and image. Performing the state’s “will to order,” the rowdy sheet, Srivatsan writes, “…is a mechanism designed to get a hold on the slippery, amorphous disorder that characterizes the lives of the underprivileged.” It allows the state to bolster its own position as the most informed mediator between identity and difference in India, keeping the classes apart in the interest of preserving the narrative of law and order.

A couple of short essays focus on the work of Henri Cartier-Bresson in India too. These are used to demonstrate his use of an acculturating language for contemporary Indian photography. This shows, in other words, the cultural modes of representation that Cartier-Bresson employed to integrate Indian reality into the globalised language of modernist photography. Srivatsan’s insight helps us trace the ways in which such global modes interacted with local, postcolonial aesthetics to create a language for new Indian modernities.

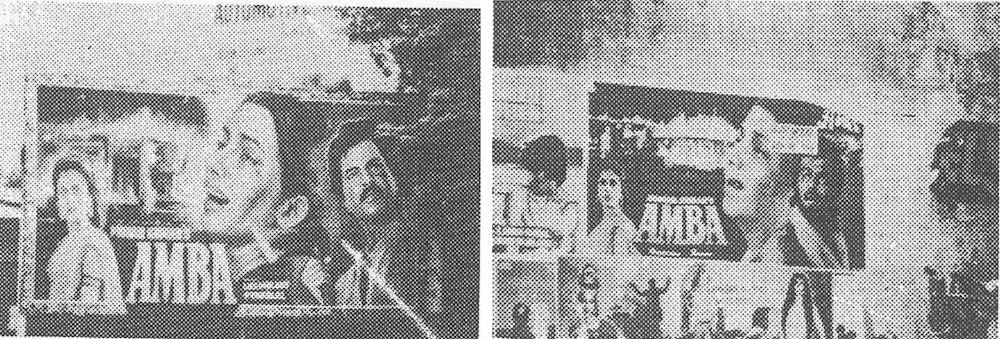

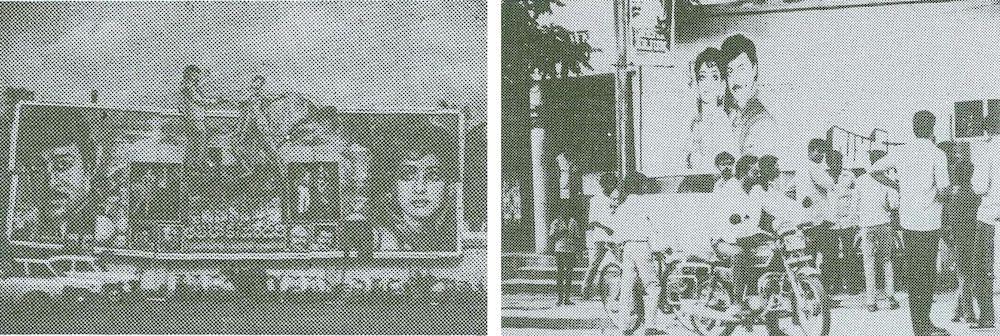

Film hoardings could often employ their visual might through their scale and detachable, cut-out imagery painted on the hoardings.

With gender, however, Srivatsan strikes a rich seam of imagery, especially in advertisements, where the female body is employed to fulfill several fantasies—from erotic longing to domestic wholesomeness. The essays—“Looking at Film Hoardings” and “The Woman in the Advertisement: Historical Explorations through a Type” circle around the issues of class and gender representation in photographs that are used for advertisements. Hand-painted hoardings were more common than photographed images since they used cheaper, more widely available labour over expensive photo processes. The art of the eccentric film hoarding creates a sensual, inviting surface that is frequently heightened by its imposing cut-out sizes and creative wrapping around theatres and buildings. They are also in conflict with the mechanical implications of photographic style and this conflict, Srivatsan argues, is frequently played out on the terrain of gender. Hoardings displayed sensual female bodies arranged in ways that could confirm the heterosexual, normative gaze of the masculine viewer on the streets. His example of Sridevi in film hoardings from the late ’80s and early ’90s shows the truth of his claims, but marks these erotic zones to be strictly one-sided even in its maleness. Not only female viewers of such hoardings, gay viewers, for whom Sridevi galvanised a complex self-image of queer visibility and desirable aspiration (attested to by a wide variety of semi-confessional, star-struck queer obituaries written after her death) get overlooked too. Choosing an ethnographic method in his essay on “The Woman in the Advertisement,” Srivatsan implicates the reader further in the strict heteronormative modes of “knowing” what the significance of women’s images were in these advertisements. This is in contrast with his discussion of an Amitabh Bachchan advertisement where Srivatsan imagines himself as the film star rather than desiring him—which is reserved for the images of Sridevi, for instance.

Srivatsan telegraphs his subjectivity to explore how Sridevi’s images on hoardings act upon him. He finds the promise of these images to enforce a structure of violence in his “engagement(s) with women,” writing that “…it defines through phantasy, what I may expect from and demand of them.”

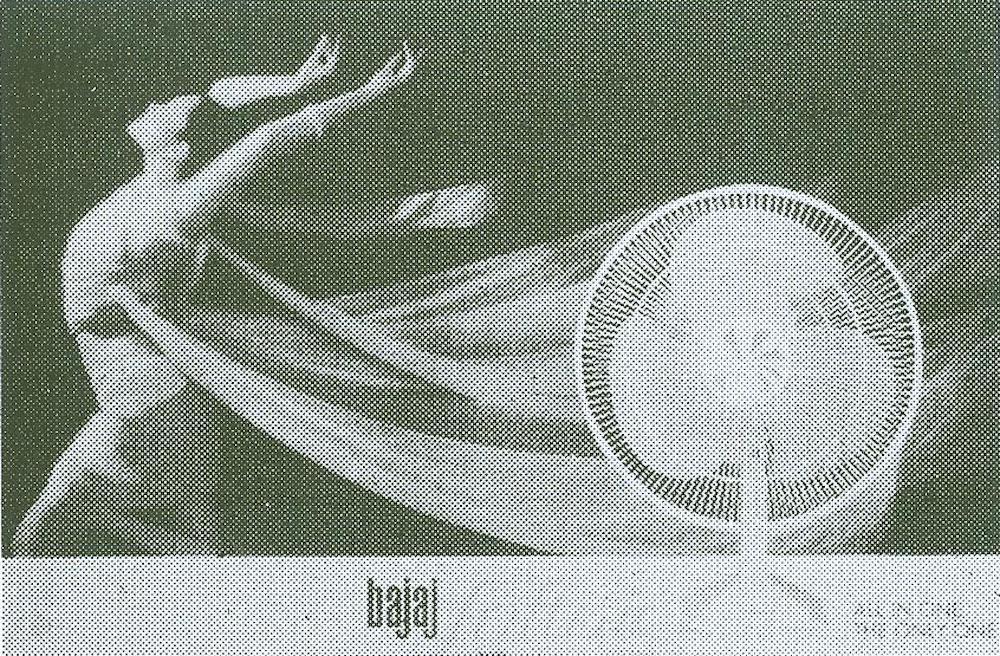

Another significant instance is revealed in his essay “Notes for a Theory of Advertising,” in which he writes short observational notes on advertisements that feature women or commodities, looking to make polemical joins between the two. He writes a desultory account of an advertisement for a table fan in which we see a woman in the background with her drapes being blown about by the advertised fan:

“I linger over her body, pause to notice her costume earrings, glance briefly at the fan advertised, ignore its brand, and look at the main copy ‘Beauty and the Breeze’… I try to read the text and the last line of the advertisement—but cannot keep my attention on them… my attention wanders.”

His performance of masculine gazing contains a complex historical residue. It allows us, the reader today, to see how such images were processed—both bodily as well as mentally—at a rhetorical distance in time, occupying registers of discourse before they were reshaped by cultures of post-analogue visuality. The looseness of style makes space for us to inhabit a mode of gazing that we may not identify with, but recognise by its texture of recording a different reality.

Advertisements like these preoccupy Srivatsan’s analysis of women’s images in the Indian mediascape. His performance of gazing at images like these give us clues about the different layers that have shaped our own attitudes to newer forms of image-making which use women’s bodies in different, perhaps more complex, ways.

To read more about the representation of women in advertising in India, please click here.

All images reproduced from Conditions of Visibility: Writings on Photography in Contemporary India by R. Srivatsan. Kolkata: Bhatkal and Sen, 2000. Images courtesy of the author and the publisher.