A History of Light and Shadow: On Cameraless Photography

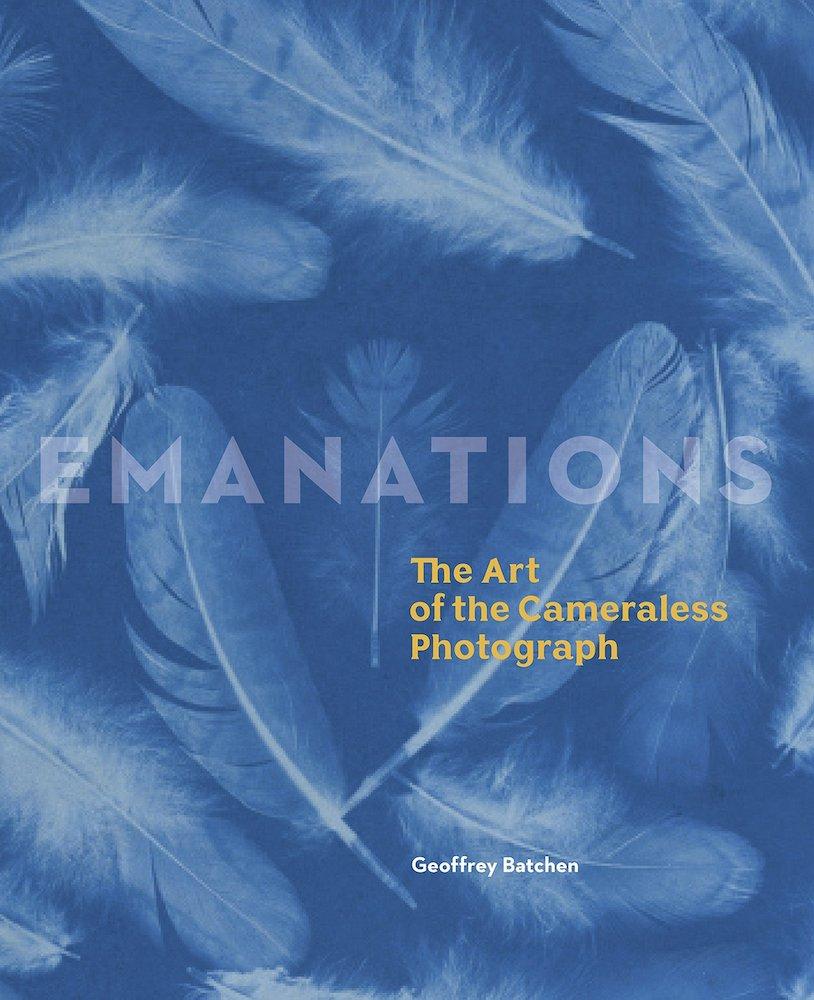

Cover of Emanations: The Art of the Cameraless Photograph. (By Geoffrey Batchen. Munich: Prestel, 2016.)

Perhaps the phrase “cameraless photography” sounds oxymoronic given the popular understanding of photography as the practice of making images with a camera; but the form has existed since—and even preceded—the birth of lens-based photography. As the name suggests, it refers to photography done without the mediation of a camera or lens apparatus. In a sense, this kind of practice strips photography to its most essential characteristic—a surface’s reaction to the presence or absence of light. This is usually achieved by placing an object in contact with a photosensitive surface and subsequently exposing both to light. Throughout its history, many distinct cameraless processes have emerged. Some of these include Johann Schulze’s chemigrams (where the image is made by painting with chemicals on photosensitive paper) and John Hershell’s cyanotypes (where a photosensitive chemical solution is applied to a receptive surface and dried in a dark place). These were later popularised by the work of Anna Atkins, Man Ray’s rayograms and László Moholy-Nagy’s luminograms, among countless others.

A Cascade of Spruce Needles. (William Henry Fox Talbot. United Kingdom, 1839. Image courtesy of the British Library.)

In his publication Emanations: The Art of the Cameraless Photograph, British art historian Geoffrey Batchen traces the unique and often overlooked history of these contact-based photographic printing processes and the potential they might hold for contemporary thinking around the medium. He argues that the invention of photography might actually be attributed to the natural philosopher Johann Schulze who discovered the sensitivity of silver salts to light in 1727. The first photographs, then, were experimental demonstrations by Schulze who pasted paper stencils of words onto a glass bottle containing a chalk and nitrous lime mixture and then exposed them to direct sunlight. As the bottle could be shaken to remove the loose salts and obscure the photographic print, these first photographs were ephemeral traces of language.

Batchen reflects:

“Throughout photography’s history the cameraless photograph has always been a subversive element, an auto-critique of everything that photography is supposed to represent. For, in rejecting the camera, such photographs also reject humanist perspective, rationalised space, three-dimensional illusion, documentary truth, temporal fixity. They bring the margin into the centre to confuse precisely that familiar, comforting distinction, and with it a lot of other distinctions too.”

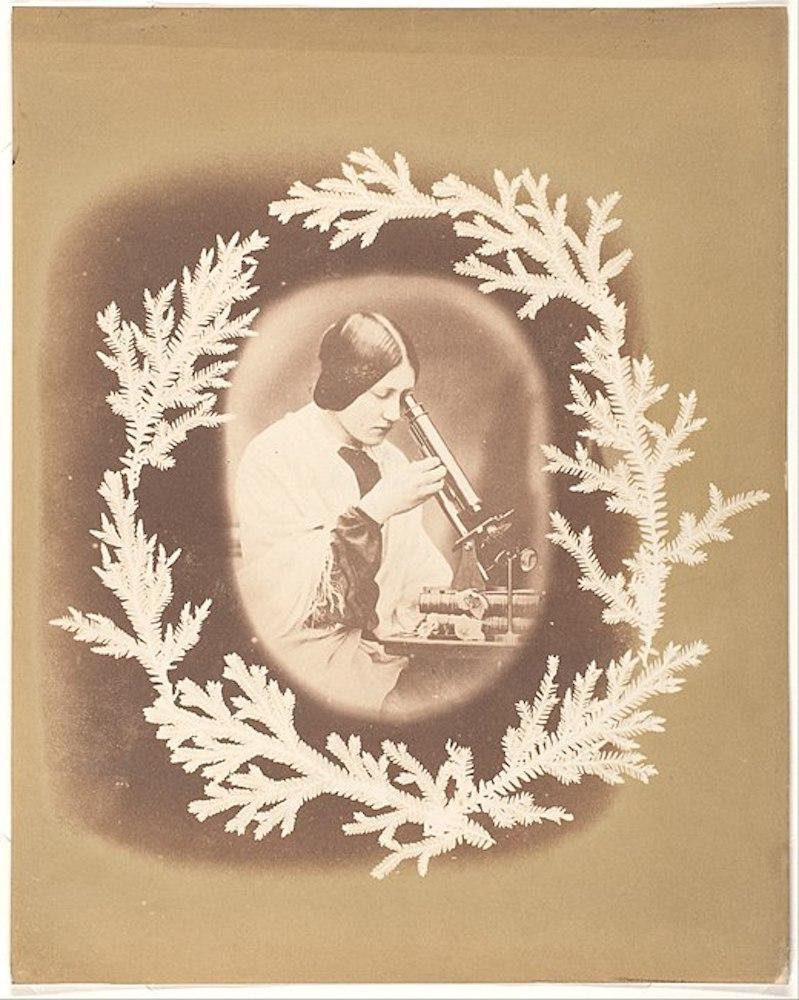

Cameraless photographs involve direct impressions—using leaves of a fern, pieces of lace, or parts of the human anatomy—resulting in a stark visual style that often breaks clear distinctions between figure and ground. As objects are pressed flat onto the picture plane, perspectival conventions (reified through popular lens-based photographs) are collapsed in these practices, often creating abstractions away from art-historical understandings of linear space. Batchen also discusses various hybrids that came about in the early years of photography, for instance, a portrait of the Welsh scientist Thereza Dillwyn (who had herself put together an album of contact prints of marine algae). This portrait—made by her father—included a camera-made image of her encircled by a wreath made of contact printed ferns. The ferns functioned as an ornament as well as an ocular metaphor for her work in photographing scientific specimen.

Thereza Dillwyn Llewelyn with Her Microscope. (John Dillwyn Llewelyn. Wales, c. 1854. Image courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.)

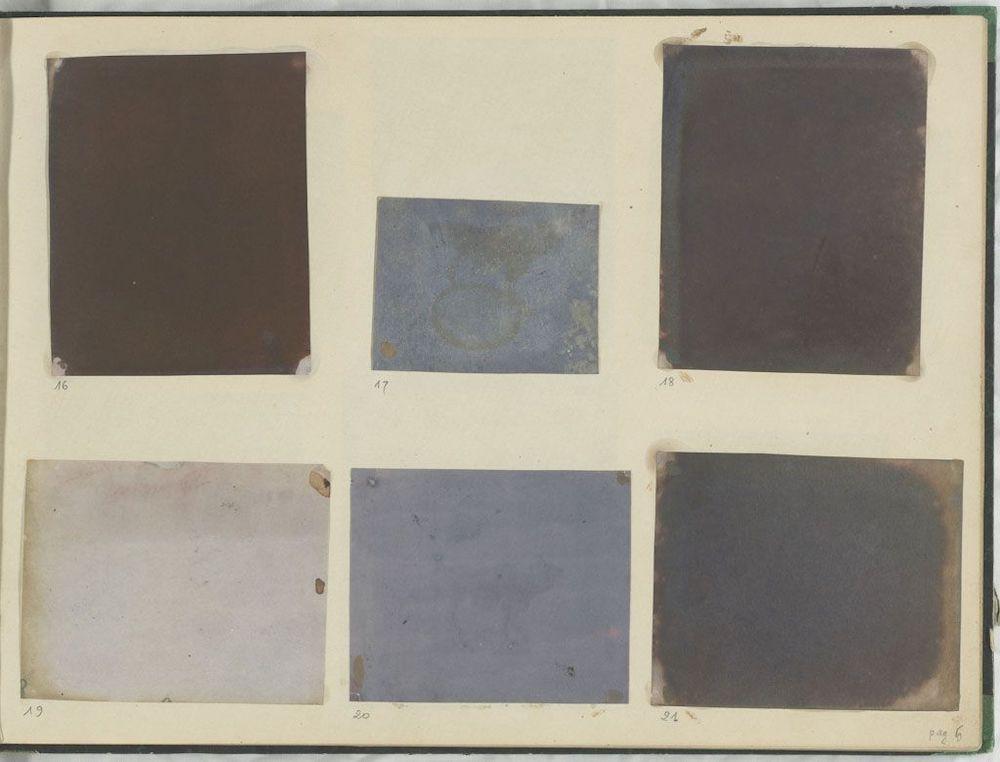

Early nineteenth-century experiments by John Draper and later, Hippolyte Bayard—involving the application of photosensitive solutions to paper and exposing them to light—can be seen as an almost philosophical attempt to photograph, capture and represent light itself. Here, photography is not centred on the realistic representation of subjects in the world and their indexical relationship to the photograph, but a material exercise to understand light, optics and to construct impressions.

Page from the Bayard Album. (Hippolyte Bayard. France, 1839–67. Image courtesy of the Getty Museum.)

To read more about Geoffrey Batchen’s work, please click here.