Fact and Fiction: A Review of Reverie and Reality

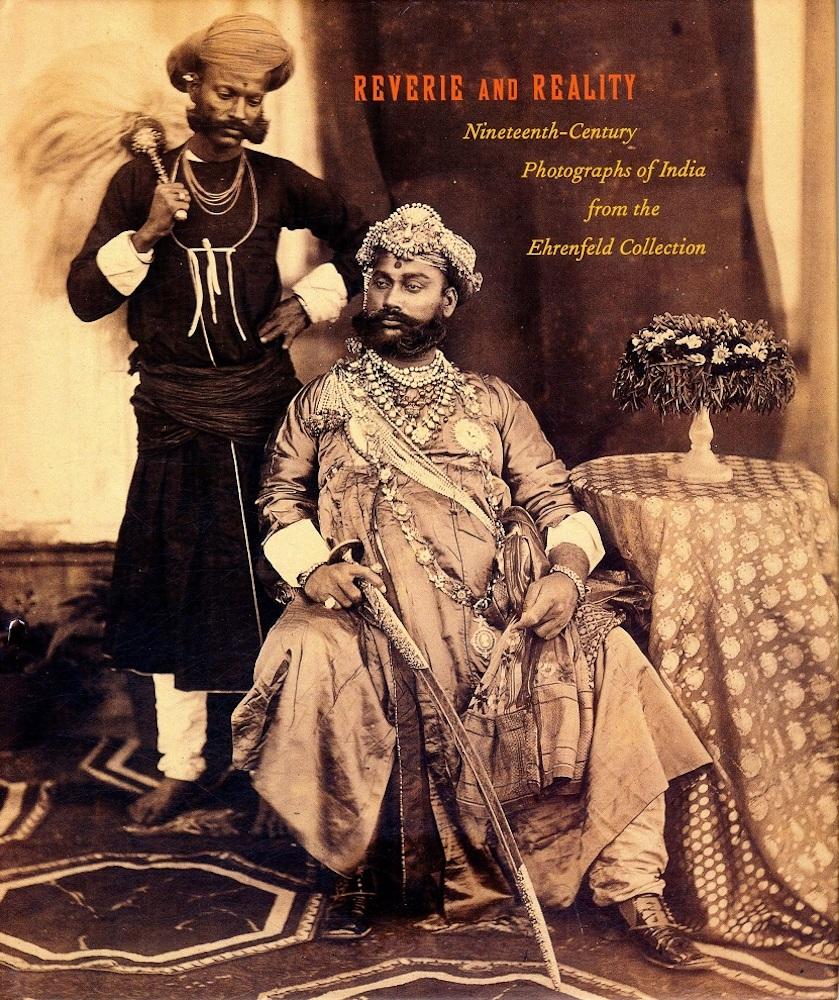

Cover of Reverie and Reality: Nineteenth-Century Photographs of India from the Ehrenfeld Collection.

Reverie and Reality is a catalogue of an exhibition held at San Francisco, from September 2003 to March 2004. Using photographs from the Ehrenfeld collection, the book also contains historical essays on the early days and practices of photography in the subcontinent—especially as they intersected with colonial modes of knowledge-making, warfare and travel descriptions for a nascent discourse on tourism. The book starts with Swiss psychiatrist and psychoanalyst Carl Jung’s enigmatic statement, made in The Dreamlike World of India: “It is quite possible that India is the real world, and that the European lives in a madhouse of abstractions… No wonder the European feels dreamlike; the complete life of India is something of which he merely dreams.” Jung wrote these words in 1939, the year when the Second World War was realised as the logical endpoint of a series of abstractions in European myth-making about their own past and the ways in which they interacted with their explicit “others” in colonies across the world. The essays, by some of the leading scholars of early photography in India, seek to unravel the ways in which such sobering realities were framed and circulated.

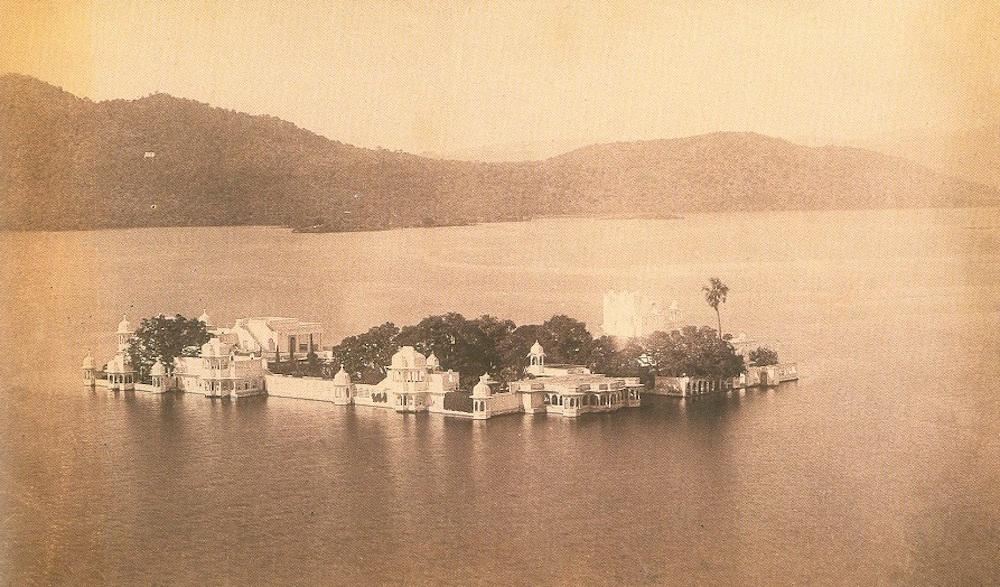

The Jag Mandir. Lala Deen Dayal is perhaps the most famous Indian name in early photography. He frequently alternated between the pictorial mode and the documentary mode, according to Robert Flynn Johnson, depending on the nature of his commission. (Deen Dayal. Udaipur, c. 1880.)

Robert Flynn Johnson’s essay deals with the complex paradoxes set off by this archive of photography—one that will not allow any neat separation between fact and fiction even as it makes polemical claims about its facticity. He dismisses the camera’s claim to any kind of objectivity, writing that the “…perception of objectivity is an illusion. Instead of a technical facility of fact, photography is a malleable medium that willfully or unwittingly can be manipulated. Photography starts as factual, scientific process and ends as a fiction.” The attempt to read this archive as one that is full of possible fictions is also a way of bypassing its frequently argued role as a documentary fact of history, or one that can afford any transparent access to the swirl of motives and practices that influenced these photographs beyond the rubric of power and knowledge.

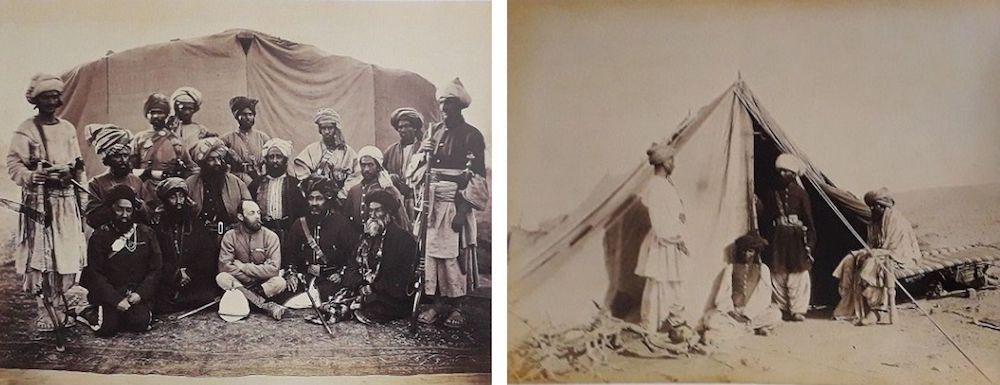

Left: Major Cavagnari and Chief Sirdars with Kunar Syed. This photograph reveals the uneasy accommodation between agents of the British Empire, like Major Cavagnari, and the local elites of Jalalabad. (John Burke. Jalalabad, 1878–79. Albumen Print.)

Right: Group of Pathan Sirdars or Chiefs. Fred Bremner specialised in making photographs of different army units “…across many Northern Indian cantonments,” as part of a typology of those in the British Indian army. (Fred Bremner. 1889. Albumen Print.)

These problems are compounded by the large number of photographers being almost exclusively “foreigners,” who were “looking in” from the outside. Johnson classifies them according to the kind of subject they focused on:

“Dr. John Murray and Linnaeus Tripe sought architectural documentation. Felice Beato documented military campaigns. Samuel Bourne pursued the picturesque. These and other photographers followed their goals with a tenaciousness that, given the harshness of climate, complexity of social interaction, and cumbersomeness of their technical apparatus, is all the more admirable.”

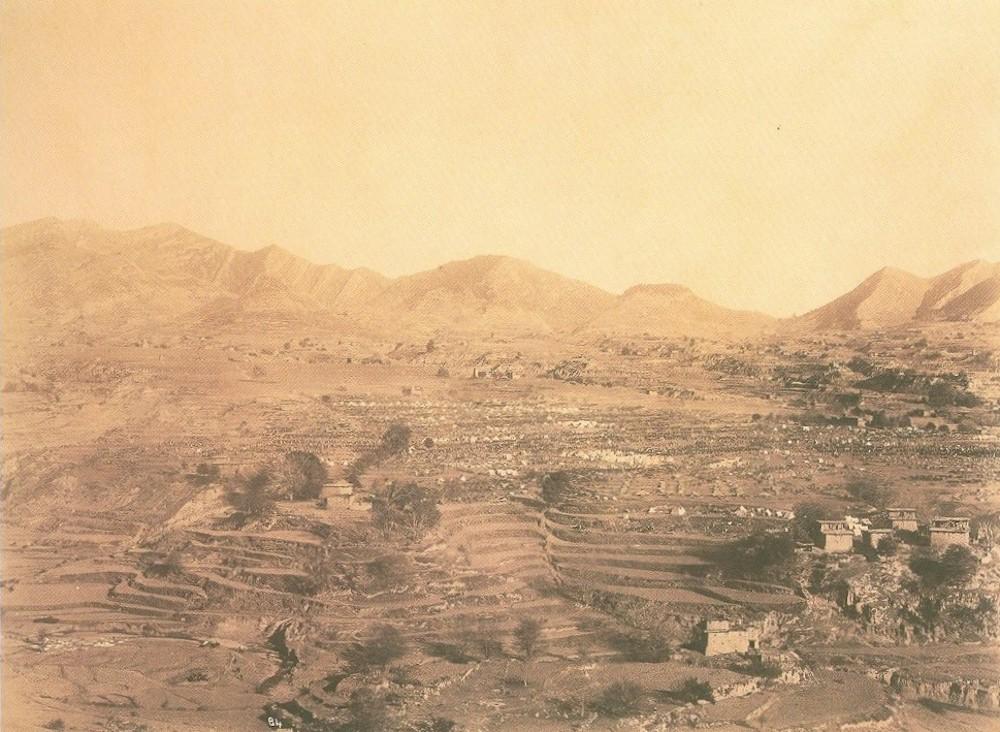

The problem of constructing a coherent image of India is confronted by the complex colonial machinery that sought to influence its own picture of the landscape. Johnson argues, however, that photographers like Bourne worked through the aesthetic fashion of his day to depict India as the “…exotic, yet serene, theme park,” to infect his audience with a fantasy of what could be, instead of what was there already. And the use of colonial aesthetic styles like the “picturesque” was not limited to Bourne or Tripe, as he reminds us of Lala Deen Dayal’s practice which ranged across similar themes as well. Deen Dayal, however, also added to an additional discourse of protest through “pictorial outrage” as he turned his focus on the victims of a famine in Hyderabad of the 1890s. This was not readily available in the work of the other photographers though, who struggled to discipline the spread of the land with their views of an “…ultimately unknowable land.”

View from Camp Maidan. Working in Lucknow and Peshawar, William Dacia Holmes was probably one of the main “competitors” of John Burke, according to Omar Khan. He photographed the Durand Mission in 1893 and also specialised in photographing frontier and military zones. (William Dacia Holmes. Tirah, 1897. Image courtesy of Omar Khan.)

John Falconer’s essay “The Early Years of Photography in India” describes the careers of photographers like William Brooke O’Shaughnessy, who worked for the Bengal Medical Service, as well as Alfred Huish and John McCosh, whose careers in photography were interlinked with their professional services in colonial institutions like the army. O’Shaughnessy’s case shows the easy manner in which professionals like him—working with new sciences of pharmacology, chemistry and galvanism—could use photography as a way to extend their interests in these allied disciplines.

Before commercial photography and daguerreotypes could be made widely available to the ordinary people, military officers formed a large portion of India’s early photographers. After the establishment of commercial studios in places like erstwhile Bombay and Calcutta, private patrons and public ones—like the East India Company—sponsored their widespread use in India for purposes ranging from personal interests in portraiture and its evolving aesthetics of representation to archaeological documentation. By the 1860s, Samuel Bourne could confidently, if somewhat exaggeratedly, claim that photography had spread all over the subcontinent and it was “…least of all, a new thing… the camera is now a familiar object; and… the majority pass it unalarmed, or their curiosity has taken the place of fear.”

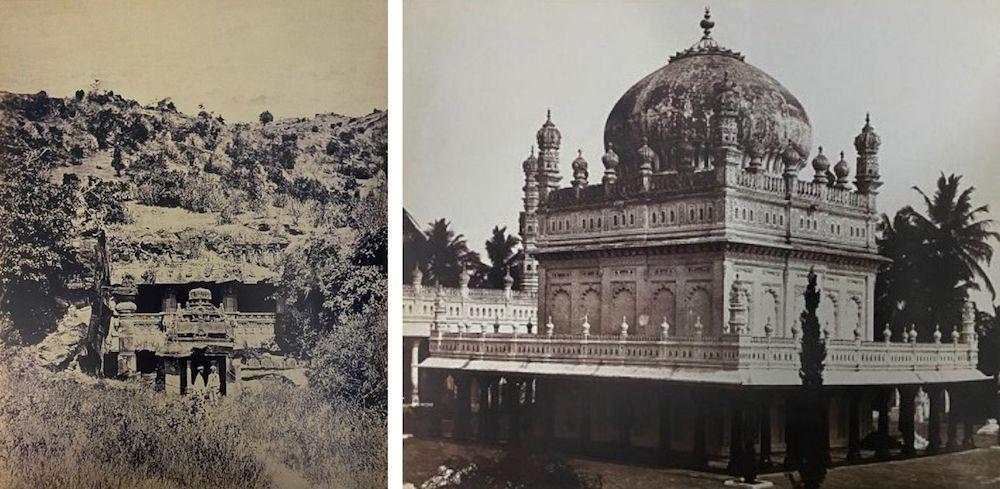

Left: Indra Sabha (Cave Thirty-Two). (Henry Mack Nepean. Ellora, 1868.)

Right: A View of the Mausoleum of Haider Ali and Tipu Sultan in the Lal Bagh Garden. (Photographer Unknown. Erstwhile Seringapatam, 1880.)

To read more about the Ehrenfeld Collection, please click here.

All images (except where noted) courtesy of the Ehrenfeld Collection. From the book Reverie and Reality: Nineteenth-Century Photographs of India from the Ehrenfeld Collection. New Delhi: Timeless Books, 2004.