The Propagandist and the Picturesque: Two Essays from Reverie and Reality

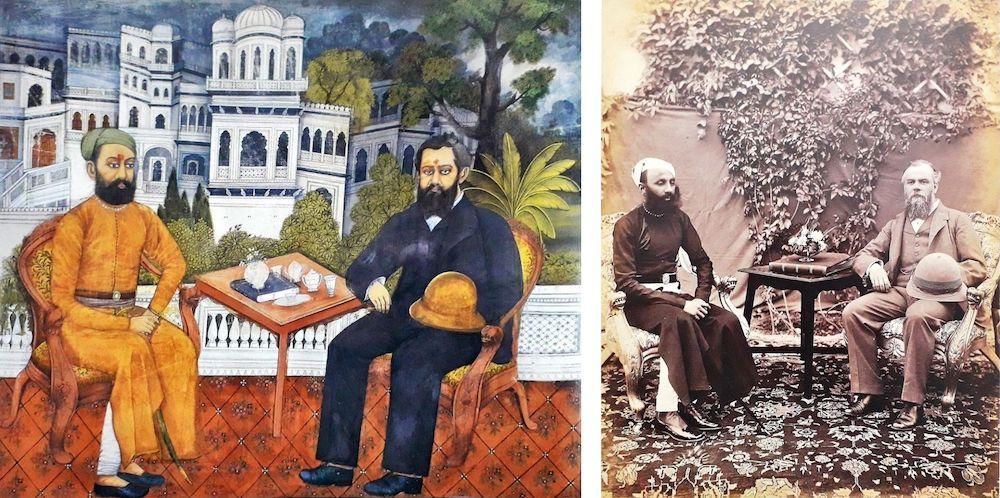

Photographs taken to cement local alliances with the East India Company or, later, the British Empire, were often touched up or fully painted to add the kind of aesthetic and political symbolism that a mechanical image could not always show. This was meant to record the meeting of Maharana Sir Fateh Singh of Udaipur (b. 1848) and Victor Alexander Bruce, Earl of Elgin and Kincardine (Viceroy of India 1894–99). The original photograph (right) is attributed to Johnston and Hoffmann of erstwhile Calcutta.

In this continuing discussion of Reverie and Reality, we focus on two essays by Sophie Gordon and Omar Khan which delve into the specific nature of a few photographic projects that are reflected in the Ehrenfeld collection. Gordon’s essay “‘Under the Sunny Skies of Ind’: Photographing Antiquities and Tribes,” describes the important role played by civilian and amateur societies like the Photographic Society of Bombay. Such societies were responsible for setting the aesthetic definitions of photography and furnishing their members with a thorough knowledge of this art form that was equally dependent on advances in chemistry and the natural sciences. The polemical claim for objectivity, which James Falconer warned us against believing uncritically, is highlighted by Gordon as an important element of its advertised success. The Photographic Society of Bombay would frequently write articles describing the accuracy afforded by this new medium in stark contrast to the work of poets and painters: “(Photography was) an Art, of which the beauty and utility are only surpassed by its truthfulness.”

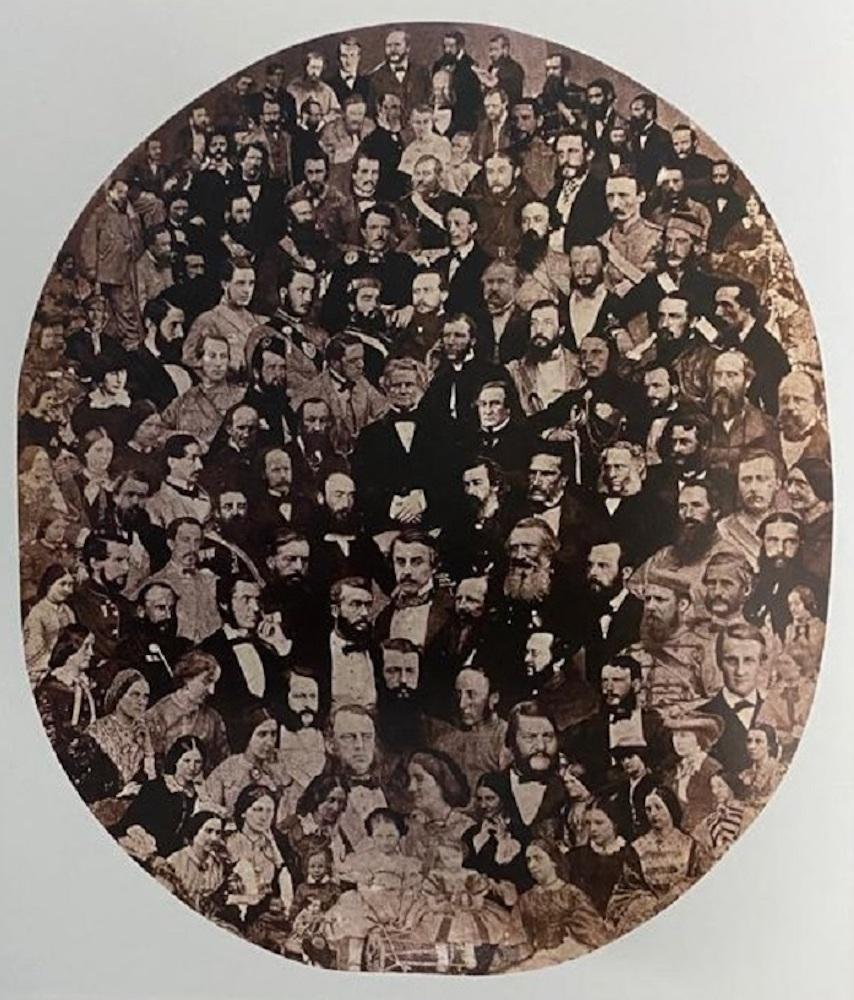

Agra Friends. (John Nicholas Tressider. 1862. Photographic Mosaic.)

Group of Remains Near Southeast Entrance to the Ambarnath Temple. A photograph taken by Shivshanker Narayen, who worked as a commercial photographer and teacher in erstwhile Bombay. (Shivshanker Narayen. Ambarnath, 1868–69. Image courtesy of the British Library.)

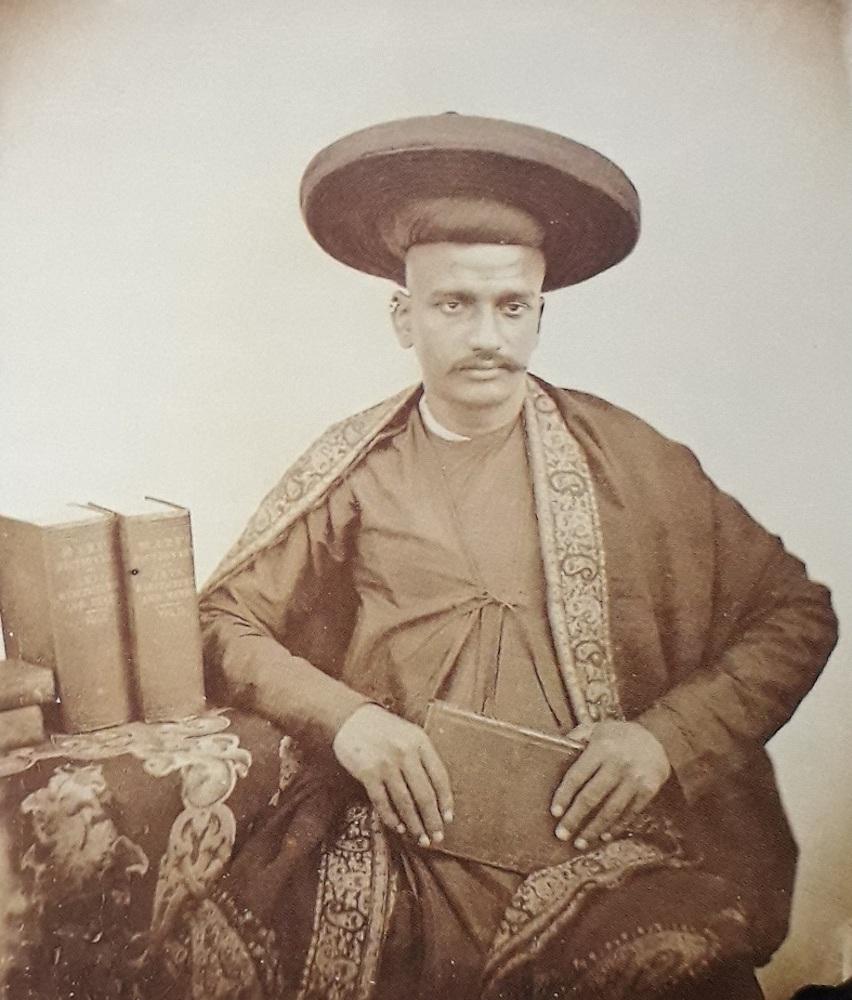

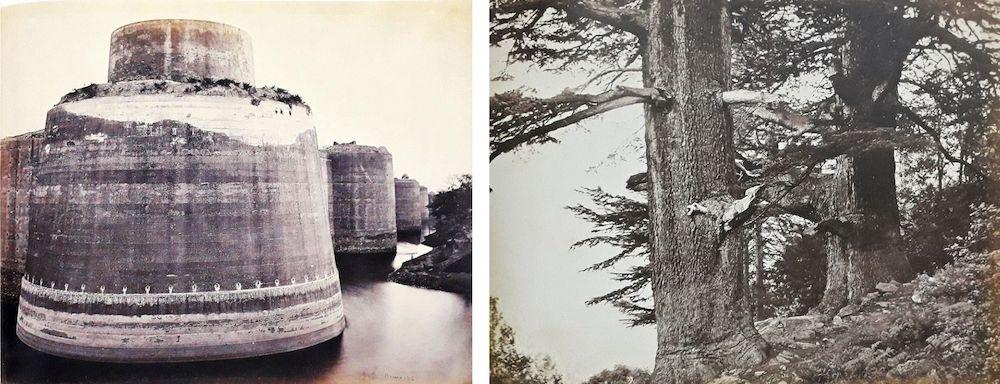

As Gordon shows, however, the photographer was still making discernible choices about the process, subject and methods of development that marked this medium to be a genuinely artistic one. Linnaeus Tripe was a Government Photographer in the erstwhile Madras Presidency; Thomas Briggs was sent out by the Court of Directors (the board that controlled the East India Company) to make pictures of the caves and temples of Western India. Others like Horatio Biden and Eugene Clutterbuck Impey pursued their own commissions, sometimes with the help of government officials and at other times, precariously without. Commercial studio photographers included some Indian names like Shivshanker Narayen, Hurrichund Chintamon and Narayan Dajee who made photographs of monuments, tribes and individual portraits of caste and profession-based Indian subjects. Their focus was limited to a few areas of the geography: “Scenes with significant colonial and historical associations; topographical landscapes that could be presented according to the prevailing aesthetics of the time; and antiquities and ethnographical studies that could be fitted into the sweeping colonial surveys which attempted to encompass the whole of the subcontinent.”

Self-Portrait. Hurrichund Chintamon was another commercial photographer who mostly relied on portraiture work. (Hurrichund Chintamon. Erstwhile Bombay, c. 1860s. Image courtesy of Private Collection, London.)

The large, exotic expanse of India inspired the threat of incoherence and plenitude for the western photographers; even if they knew where to point the camera, how were decisions about subject-making taken? Gordon says that the decision was taken on the basis of the final consumer of the image—whether it was a paying member of the public, or the government. The idea of the image responding to a popular demand created by colonial myth-making was a strong one. It explains the mass of images that concentrate on sites of controversy where British power was either challenged or routed. The images could then become charged with propagandistic energy that was, in turn, aided by the picturesque mode of alienation in a strange landscape. Felice Beato contributed to this archive with his photographs of the Residency at Lucknow. “The image of the Residency,” Gordon writes, “appears over and over in photograph albums, and later in postcards. The ruins became a pilgrimage site; the image of the tower became an icon.”

Left: Fort of Dig from the Northwest. (Samuel Bourne. Rajasthan, 1865.)

Right: Simla in Winter. (Samuel Bourne. Shimla, 1867–68.)

Even as the photographs of surveyors, military men and adventurers revealed implicit tensions—especially political and cultural, like in the image of Major Cavagnari posing with the Chief “Sirdars” of Afghanistan at Jalalabad (taken by John Burke)—between them and their subjects, the larger apparatus of the photographic trade existed without any such tension. In other words, “…no tension is apparent between the artist, the businessman, and the government employee, despite their different underlying reasons for photographing India.” Colonialism may have provided the structure and context for these photographs to be taken the way they were, but artists were always making individual choices. Their choices allow the viewer to find different significances for these archives—other than the purely utilitarian or commercial objectives that defined their existence in the past.

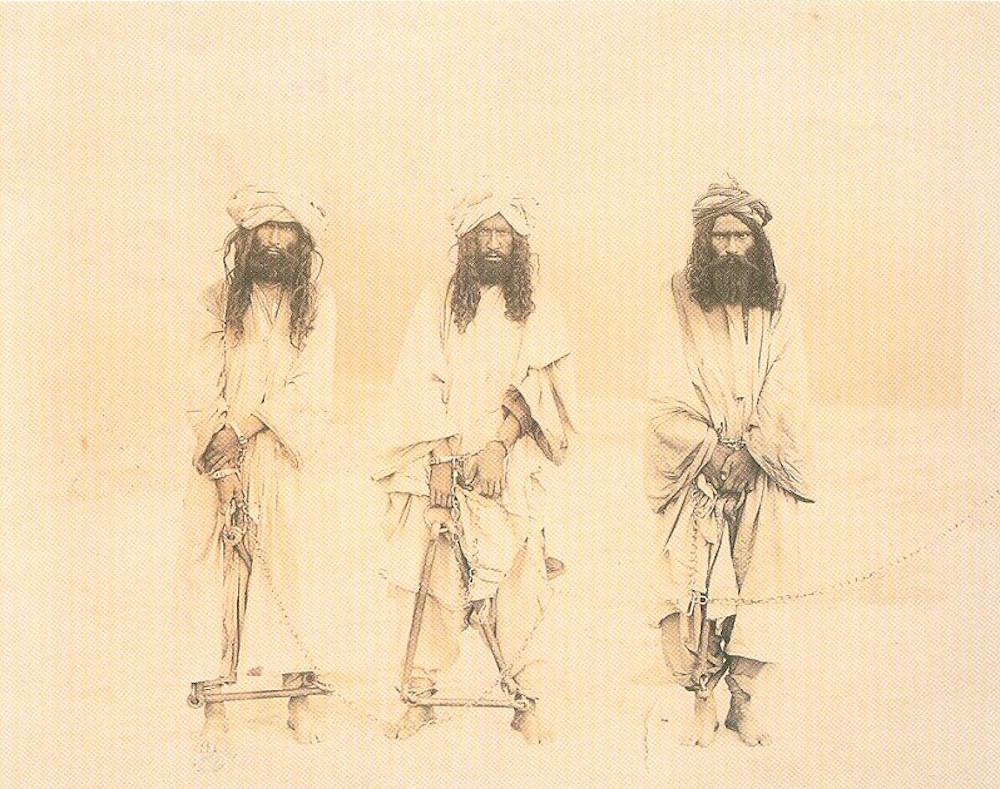

Omar Khan’s essay, “War Photography in Nineteenth-Century India and Afghanistan” adds further examples to emphasise the indisputable relationship between war, colonial expansion and the use of photography. The survey of landscape, people and monuments were often complicit in projects of colonial takeover, especially during the wars in Afghanistan and the Mutiny of 1857. Khan adds that a logical corollary of war photography was “…peace photography, or what was more usually known during the Raj as durbar (grand meeting) photography.” Some of the major photographers he explores in this essay include John Burke, William Baker (who made photographs of the Ambala campaigns of 1863) and James Craddock. Classifying the relationship between the new rulers and the local elite, or those between subject peoples and colonial administrators were the chief purposes of the photographic expeditions that tagged along with British armies through the dangerous and remote landscapes of the North-West frontier.

Omar Khan’s essay explores the ways in which photography was implicated in the war projects of the British Empire—like the ones they fought in Afghanistan. This photograph shows the Baloch tribal leaders who led the Mari Rising, October 1896. (Photographer Unknown. Afghanistan, 1896–97. Image courtesy of Omar Khan.)

It is, once again, the reference to much-circulated myths of the time that gave the power of suggestion to photographs like the one Beato took of the “Kashmir Gate,” revealing a façade that was peppered with canon shot during 1857. It creates the impression of a landscape under siege, like the Black Hole incident of erstwhile Calcutta in which Nawab Siraj ud-Daulah’s troops held British prisoners in a Fort William dungeon. As more commercial studios took up the work of photographing war campaigns and the consequences of warfare, this body of images grew into a rich, multifaceted archive that spoke to the wealth of motivations and cross-purposes that held the British Empire in place.

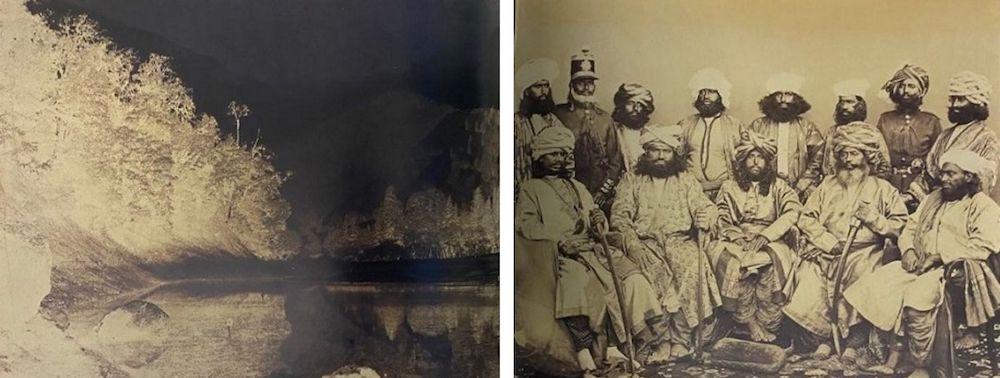

Left: Landscape with Female Figure. John Murray’s waxed paper negatives give us a sense of the ethereal, dreamlike scan that Indian reality presented into the European unconscious—as suggested by Carl Jung. (John Murray. Nainital, 1858–62. Waxed Paper Negative.)

Right: The Nawab of Bahawalpur, Sir Sadiq Muhammad Khan IV and His Entourage in Durbar, 1880s. (Photographer Unknown. Bahawalpur, c. 1880s.)

To read more about photography in India in the nineteenth-century, please click here, here and here.

All images (except where noted) courtesy of the Ehrenfeld Collection. From the book Reverie and Reality: Nineteenth-Century Photographs of India from the Ehrenfeld Collection. New Delhi: Timeless Books, 2004.