Nation-Building and Photography: Marg Magazine’s 1960 Issue

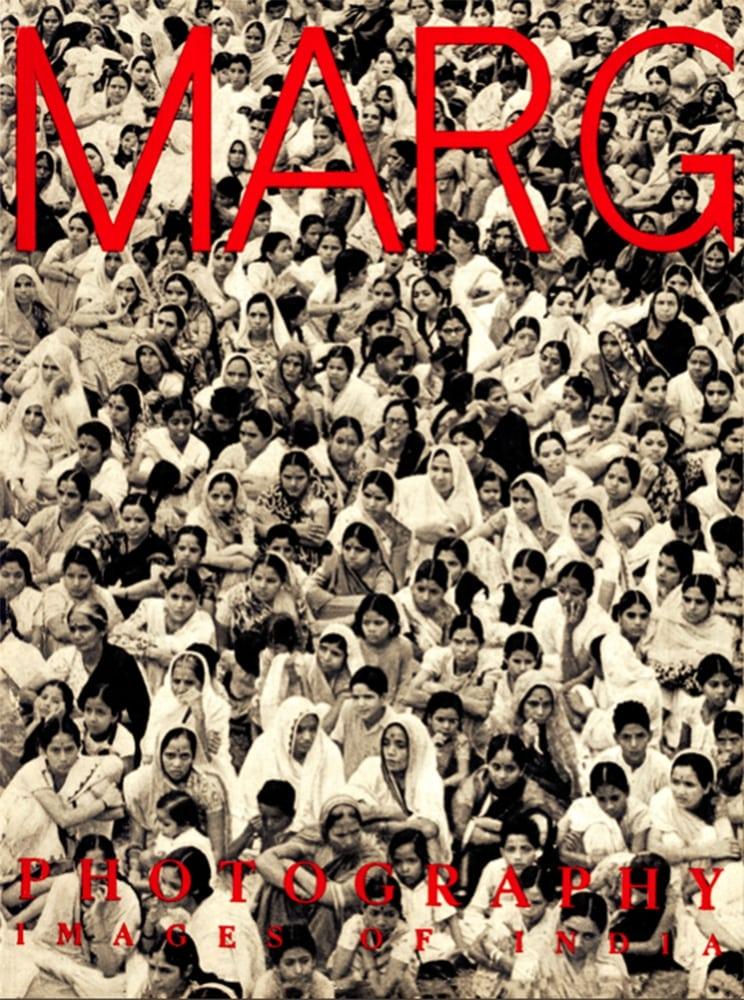

Cover of Marg Magazine’s 1960 issue titled Photography: Images of India. (Photograph by W. Williams.)

The 1960 issue on photography by Marg magazine was titled after the exhibition Images of India, an oft-cited source within the study of photographic histories and practices in the subcontinent.

Marg, meaning pathway, is also an acronym for Modern Architectural Research Group. It was founded by writer and publisher Mulk Raj Anand in 1946 with its inaugural October 1946 issue titled Planning and Dreaming. The inception of the magazine—on the brink of independence—was closely linked to the nation-building exercise that was underway. It documented and explored different forms of built, visual and performing arts and how they contributed to this goal.

Photography was addressed in this particular issue through a similar lens—as an art form that deserved due recognition for its potential to contribute to the new nation’s image of progress and development. This is most clearly evidenced through the event that inspired this issue. The photographic exhibition Images of India was held at the Jehangir Art Gallery in erstwhile Bombay between 12 February and 21 February 1960. This exhibition’s curatorial idea and design was inspired directly by The Family of Man, another widely known and ambitious photographic exhibition. Curated by Edward Steichen at the Museum of Modern Art (New York), it had travelled to India and was showcased at the Jehangir Art Gallery in 1956. The Images of India exhibition offered a unique opportunity for documentary photography pertaining to diverse themes—such as work, festivals, growth, family and pain—to be displayed within a single exhibitionary framework.

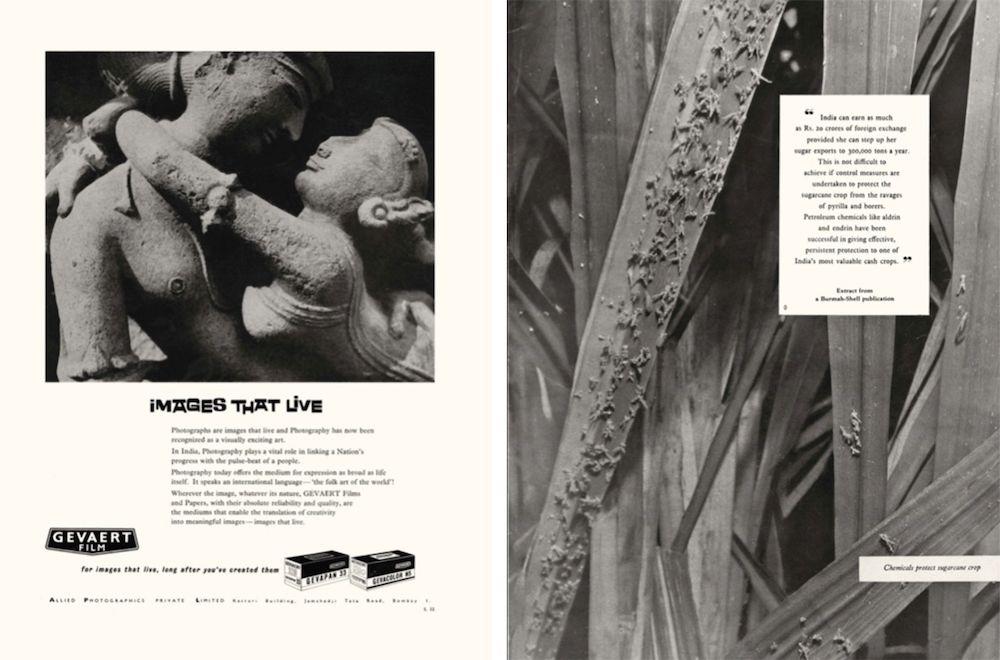

Left: Images that Live. (Advertisement for Gevaert Film.)

Right: Chemicals that Protect Sugarcane Crop. (Advertisement for Burmah-Shell.)

Using the Images of India as a starting point—while taking a closer look at its various inspirations—this edition of the magazine investigated the many facets of the photographic form. Despite this, the publication was predominantly textual and focused on the broader photographic landscape—the practice of amateurs; India’s position on a global stage; professional engagements for photographers, especially advertising; and a survey of how photography had evolved since its arrival in India. For an issue on photography, the main image content is surprisingly restricted to the portfolio section, which only carried images from the Images of India exhibition; yet it poses a unique perspective on photography’s status at the time. Thus, I look at the images and textual essays as two distinct strands of what the issue attempted to do.

While the photographs from the exhibition are contained in the portfolio section, we see another kind of printed image in the magazine in the form of advertisement imagery—mostly featuring landscapes and industry. There is an interesting way in which these two kinds of images can be linked within the issue. One can see that several of the practitioners featured in the exhibition very often also did commercial photography. Commercial photography at the time was a platform available to some photographers—mostly for advertisement images. However, this issue provided an opportunity for such images to be seen through an artistic lens as we see instances where documentary photography was often repurposed for advertising images within the narratives of nation-building.

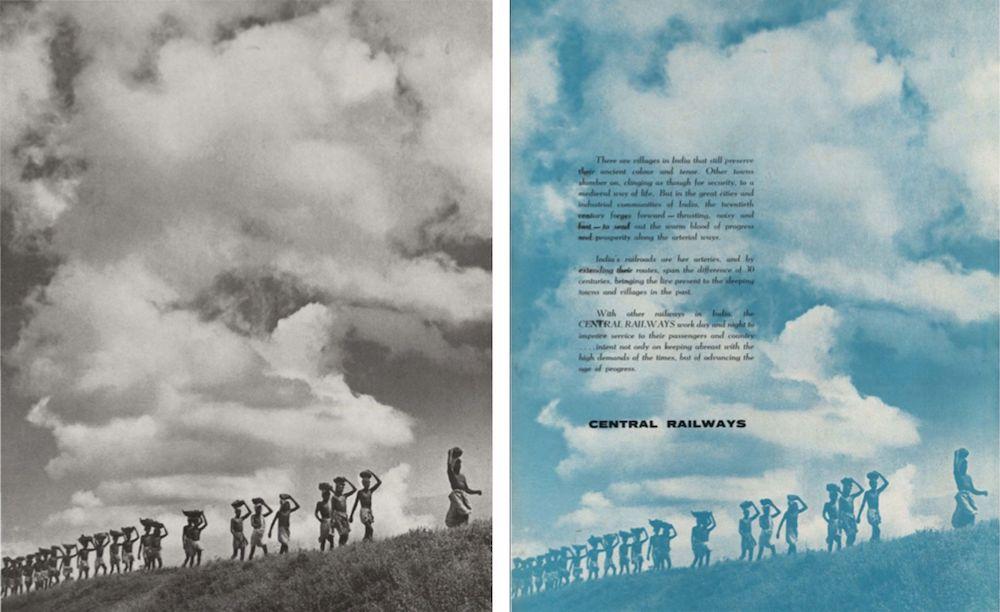

Left: Photograph from the section “Work” featured in the exhibition and reprinted in the Portfolio Section of the magazine. (Photograph by Pramod Pati.)

Right: Advertisement for Central Railways appearing in the same issue. (Photograph by Pramod Pati.)

A familiar use of commercial photography is seen in an advertisement for the Central Railways featured in this issue. On a blue-tinted image of construction workers—walking in a single file, with the vast expanse of a clouded sky covering most of the image—a short text highlighting the role of the railways in India’s progress is overlaid. This photojournalistic image by Pramod Pati also appears later in the portfolio section under the theme “Work.” In both contexts, the narratives exemplified a push towards robust industrialisation—including production of steel and chemicals—that had been the focus of the new nation since the 1950s.

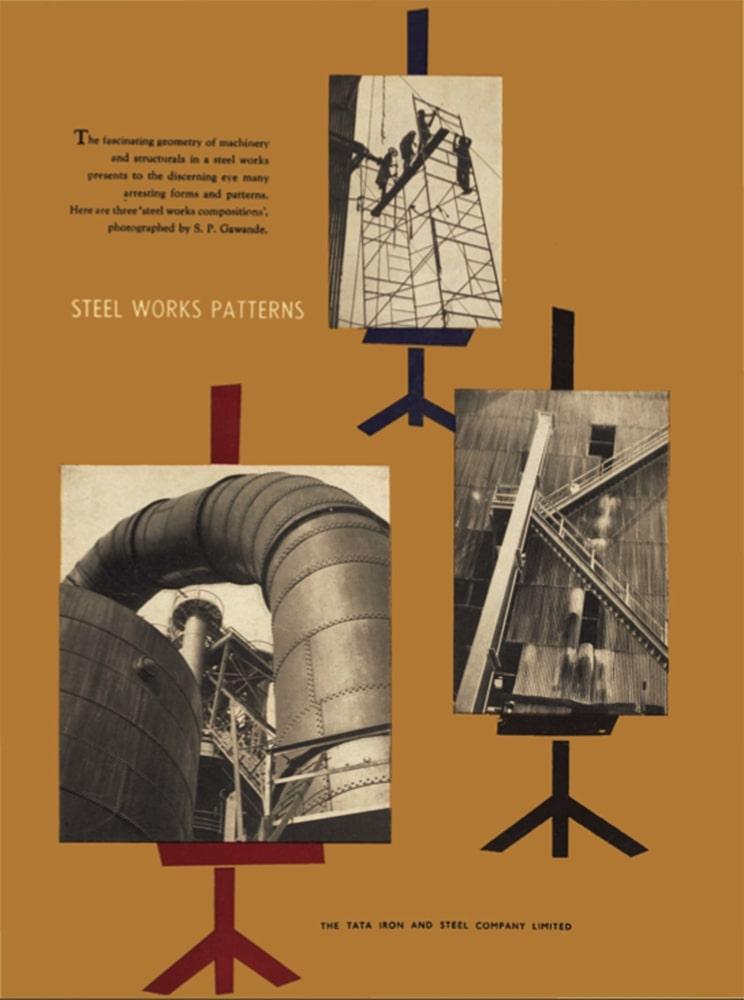

Here, photojournalistic images of industrial growth are placed on easels (as works of art) while operating within a commercial logic of advertising. (Advertisement for Tata Iron and Steel Company Limited. Photographs by SP Gawande.)

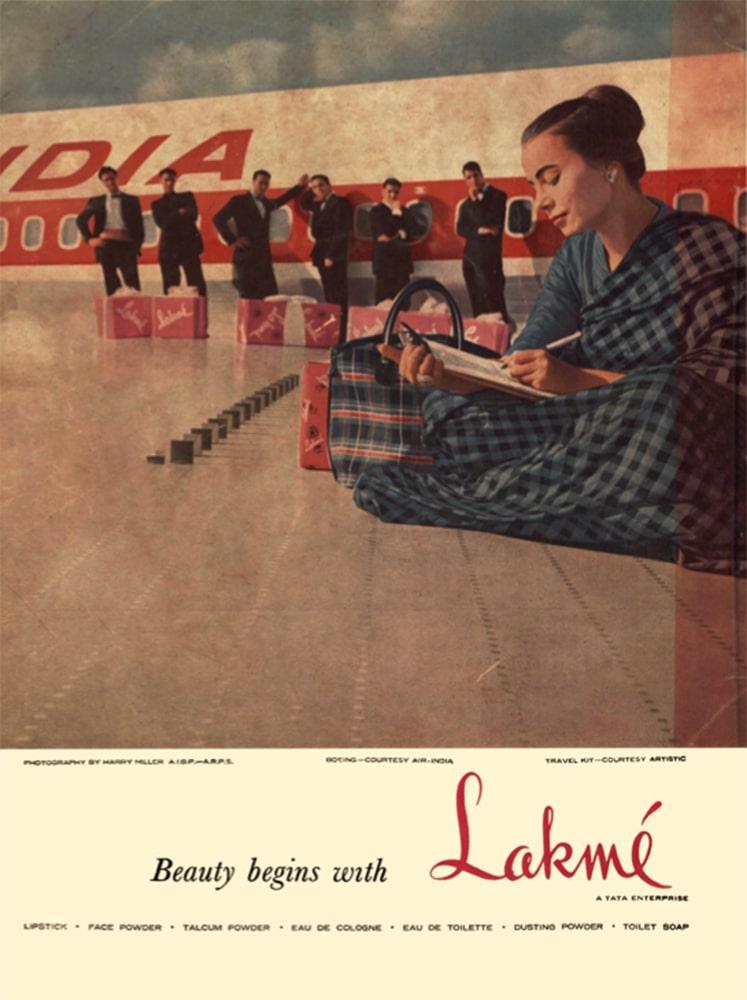

Other such advertisements offer a glimpse into the fluid nature of photography at the time. In an advertisement for the Tata Iron and Steel Company within the issue, images are foregrounded to create a complex message. Featuring landscapes of industrial locales photographed by SP Gawande, the advertisement reveals the “…fascinating geometry of machinery and structurals in a steel works” seen through interesting compositions and patterns. These images are presented as works of art that seem to operate within the commercial logic of advertising while simultaneously chronicling narratives of industrial growth. Similarly, on the last page, there is the rare colour image by Harry Miller, as a part of an advertisement for Lakmé. A creative visualisation on the powers of makeup, it features an Air India plane in the background, referencing an iconography of modernity.

Beauty begins with Lakmé picturises the “modern” Indian woman with the backdrop of an Air India plane. (Advertisement for Lakmé. Photograph by Harry Miller.)

RJ Chinwalla, who wrote a regular column on photography in the Times of India, was the guest editor for the issue and contributed an essay on “Contemporary Trends in Indian Photography.” JN Unwalla, the co-founder of the Camera Pictorialists of Bombay, a camera club started in March 1932, also contributed to the issue through an essay titled “Indian Photography—50 Years.” In their respective pieces, both have identified advertising as a space that recognised photography as an artistic practice, providing photographers with a platform for artistic expression as well as support. Thus, there was an industrial network which enabled photographers to earn a livelihood while expressing their craft, in the absence of any recognition or support by the government.

By featuring these various advertisements, while unpacking the legitimacy of photography as art through its textual interventions, the magazine offers us an understanding of the landscape of photography in the 1960s. The presence of these advertisements indicate towards a creative flexibility with regard to how photography had come to be seen in the 1960s—from photojournalism to commercial photography, often in service of the nation.

All images from Photography: Images of India. Marg Volume XIV Number 1. December 1960. Images courtesy of the Marg Archives.