Building Modern India: Jeet Malhotra’s Photographs

“Take photographs of the workers carrying sheet metal or piles onto the roof in the midst of concrete elements.”

This was one of the instructions given by Le Corbusier to architect-photographer Jeet Malhotra, who had joined Corbusier’s team as a junior architect. Tasked with documenting the ambitious Chandigarh project, a large number of Malhotra’s photographs from that period are now archived as a part of the Pierre Jeanneret fonds—a digitally accessible collection of the personal activities and professional practice of architect Pierre Jeanneret, available at the Canadian Centre for Architecture. Malhotra’s photographs form a part of the material from Chandigarh, where Jeanneret collaborated with his cousin, Charles-Édouard Jeanneret—better known by his pseudonym Le Corbusier—to develop government projects in the city.

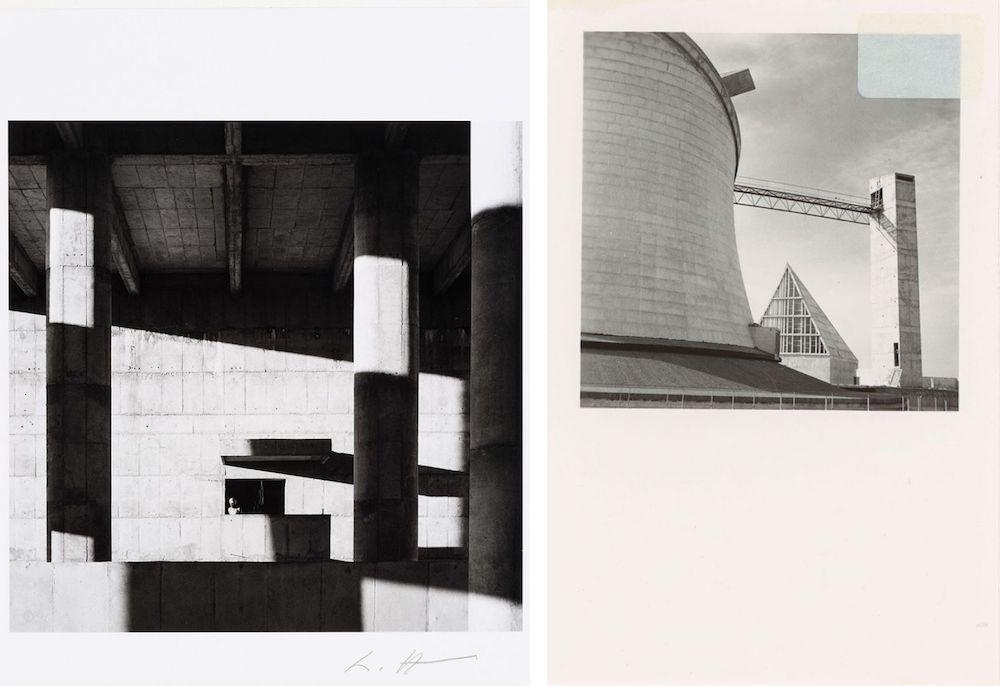

Left: Partial View of a Façade of the Secretariat Building. (Lucien Hervé. Chandigarh, 1961.)

Right: View of the Assembly’s Hyperboloid, Pyramid and Elevator Tower Under Construction, Capitol Complex, Sector 1. (Jeet Malhotra. Chandigarh, 1961–64.)

The collection consists of images—taken between the 1950s and 1970s—that cover the process as well as the final structures by Corbusier; the furniture designed by Jeanneret; and finally, images of the buildings designed by Malhotra himself. It is evident in Corbusier’s sketchbooks that he was actively thinking about photography and how the medium could capture his vision of this iconic modernist project.

Hungarian-French photographer Lucien Hervé’s 1955 images were the world’s first encounter with the project, marking the completion of Le Corbusier’s High Court building. These were widely seen and circulated in international media even in the subsequent years. They were also published in numerous issues of the MARG magazine. As art historian Atreyee Gupta writes in “Dwelling in Abstraction Post-Partition Segues into Post-War Art,”

“Hervé’s lens offered no knowledge, no comprehensive view of Chandigarh, so to speak. The monumental architecture of Chandigarh—residential blocks that filled up entire segments of the city or the bold structures in the capital complex framed by acres of empty space—formed a corpus so vast, so new, and so alien, that they could perhaps only be assimilated through such fragmentation.”

Devoid of any human presence, Hervé’s images consisted of artistic compositions true to the modernist aesthetic, relying on the dramatic effects of light and shadow to highlight Corbusier’s geometric constructions.

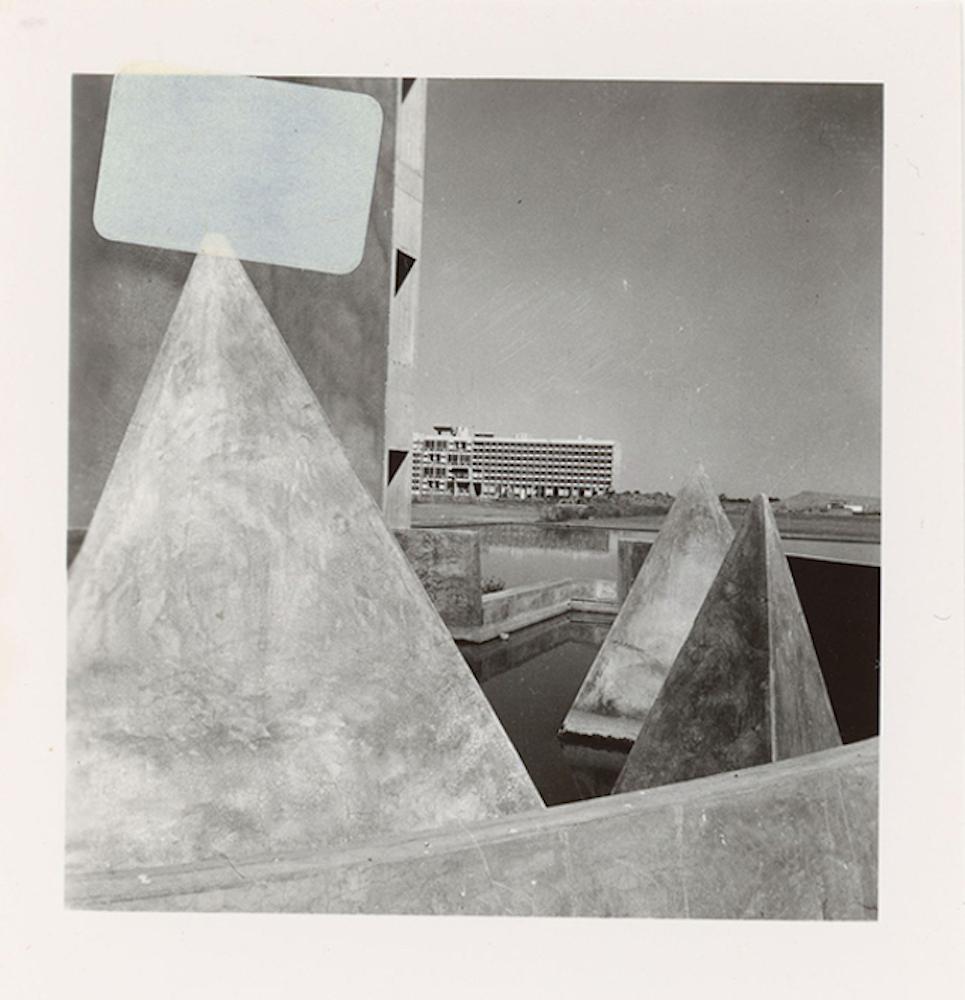

Partial View of the Secretariat from a High Court's Water Retention Basin, Capitol Complex, Sector 1. (Jeet Malhotra. Chandigarh, 1958–65.)

Following Hervé’s stint in India, Malhotra—who had already been in Corbusier’s employ—took on the charge of photographing Corbusier’s work. Unlike Hervé’s images, which celebrated the details of Corbusier’s architecture, the frame begins to widen in Malhotra’s images. For example, in an image titled “Partial View of the Secretariat from a High Court's Water Retention Basin, Capitol Complex, Sector 1, Chandigarh,” there are triangular forms from the roof of the High Court which draw our eye towards the Secretariat building in the background, with its perfect horizontals. There are other images in the series that juxtapose the two buildings as well.

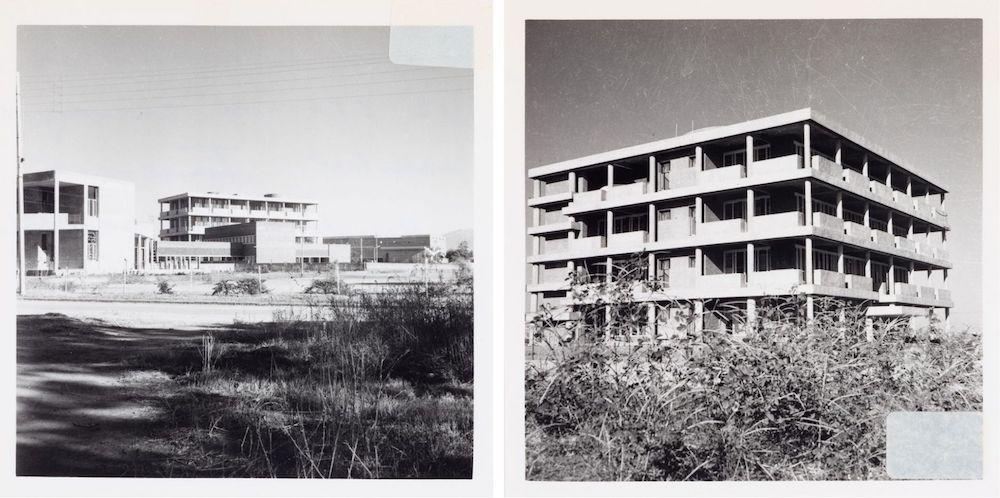

Left: Office Building in Chandigarh. (Jeet Malhotra. Chandigarh, 1964.)

Right: State Library, Sector 17 A, Chandigarh. (Jeet Malhotra. Chandigarh, 1958.)

Another example of Malhotra’s widening frame is his inclusion of the land that these buildings were being built on. Mostly barren with scattered weeds and trees, these images seem to represent an almost blank canvas of the newly independent nation which—through architecture—was being ushered into modernity. As Gupta notes, “(Malhotra’s) photographs then were not timeless and placeless in quite the same way as Hervé’s could claim to be. Malhotra’s photographs of Chandigarh, in other words, could not function as a supplement to Le Corbusier’s buildings in any other part of the world.”

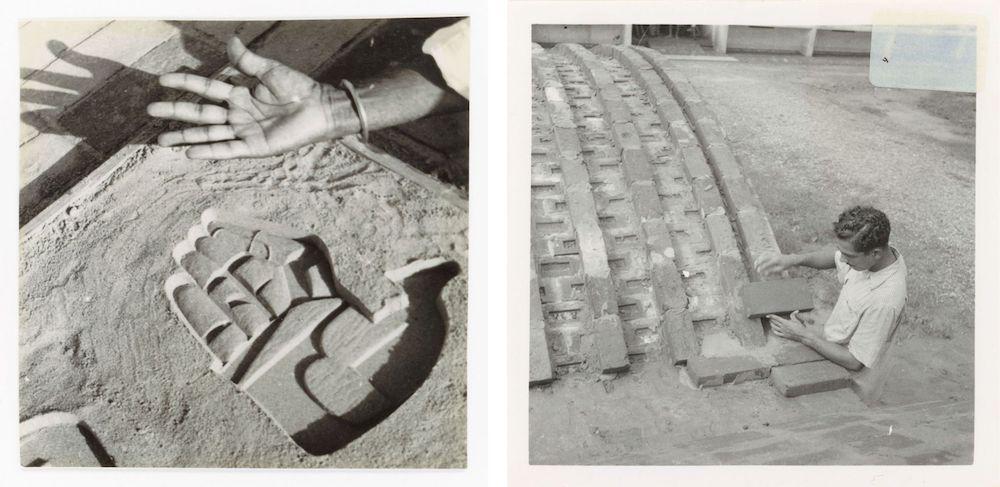

Left: View of a Bas-Relief of an Open Hand Sign by Le Corbusier and an Unidentified Right Hand. (Jeet Malhotra. Chandigarh, 1956.)

Right: View of a Construction Worker Laying Bricks. (Jeet Malhotra. Possibly Chandigarh, 1956–65.)

The other important feature of Malhotra’s images is the way they captured the workers involved in this project. A part of this was motivated by Le Corbusier’s instructions—after all, Corbusier arrived in India in 1951 at Nehru’s invitation to help realise his vision of a modern India, moving beyond its colonial past. However, Malhotra positions his work within a similar narrative as his images focus on the worker as “builders” of these constructions and, by extension, the “modern” nation. This independent, nation-building approach continues in Malhotra's later work as well, seen in his documentation of the Bhakra Dam.

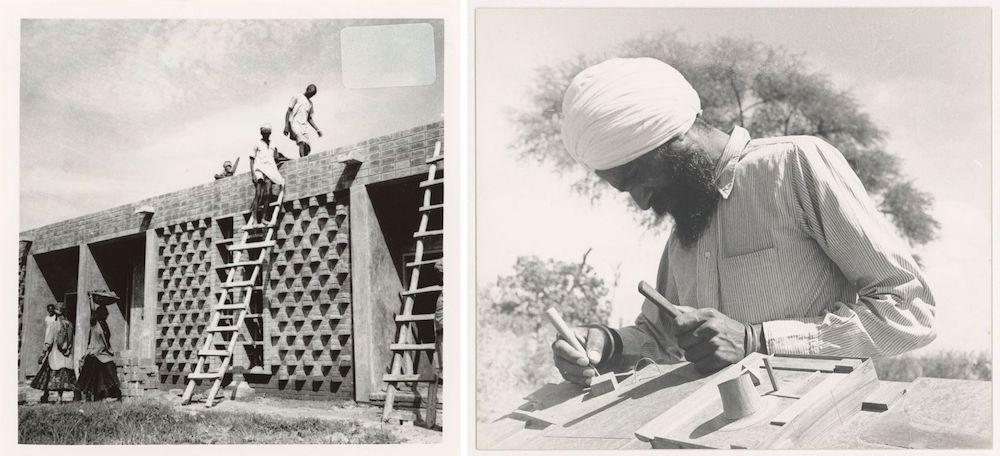

Left: View of Houses for Peons Under Construction, Sector 23. (Jeet Malhotra. Chandigarh, 1956.)

Right: Portrait of the Model Maker, Rattan Singh, at Work on the Model for Capitol Complex, Sector 1. (Jeet Malhotra. Chandigarh, 1960.)

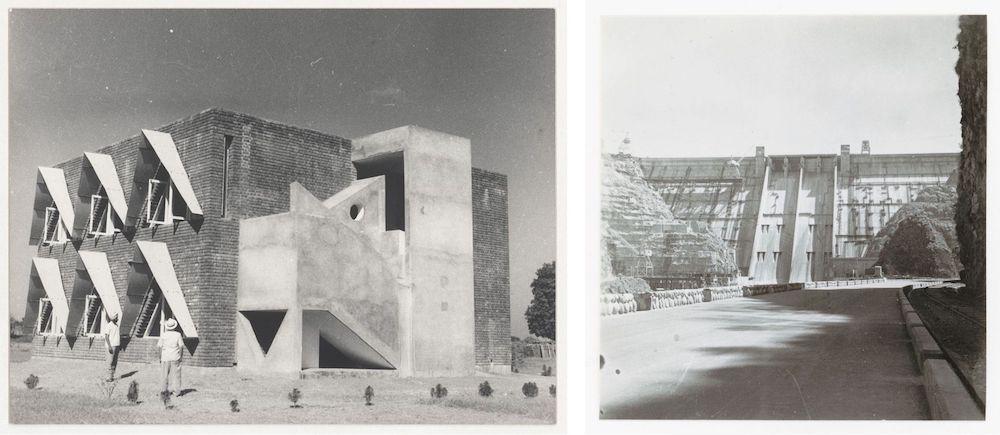

Left: View of an Office Building. (Jeet Malhotra. Ludhiana, 1953–65.)

Right: View of the Bhakra Dam Under Construction. (Jeet Malhotra. Himachal Pradesh, 1958.)

As a part of the collections, we also see photographs of the furniture designed by Pierre Jeanneret and Le Corbusier, to which Malhotra brings the same sensibilities as his architectural photography. Later, he extended his tryst with photography by capturing the works of other architects like Parmeshwari Lal Verma. Malhotra also photographed some of his own work and that is where we see some further explorations into the medium. Truly emphasising forms, these images highlight the constructions as grand monuments (in a way similar to what Hervé’s photographs were doing). Another set of images by him include the documentation of the Bhakra Nangal, a concrete gravity dam on the Sutlej River in Himachal Pradesh, thus truly capturing “the temples of modern India” as Nehru referred to the Bhakra Nangal Dam in 1954.

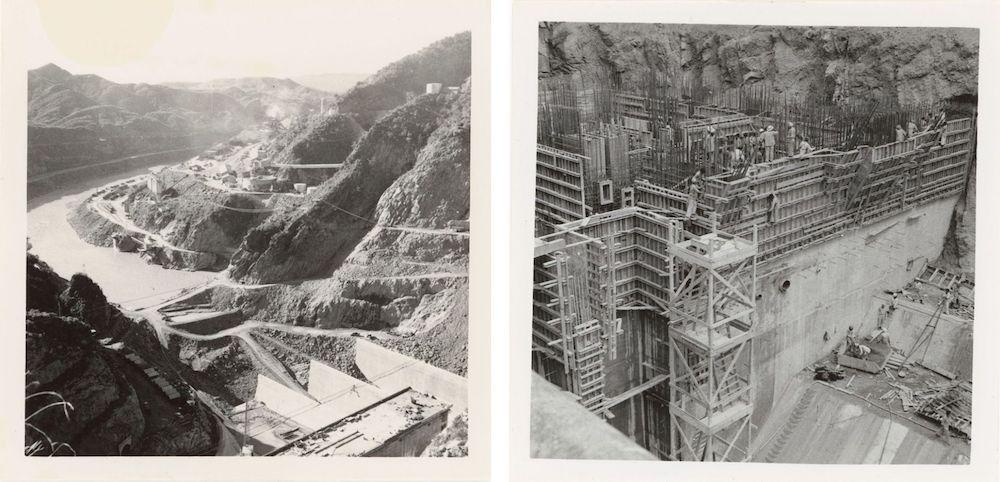

Views of the Bhakra Dam Under Construction. (Jeet Malhotra. Himachal Pradesh, 1957.)

All images courtesy of the Pierre Jeanneret fonds, Candian Centre for Architecture.