Capturing Line and Plane: Modernism in Architecture and Photography

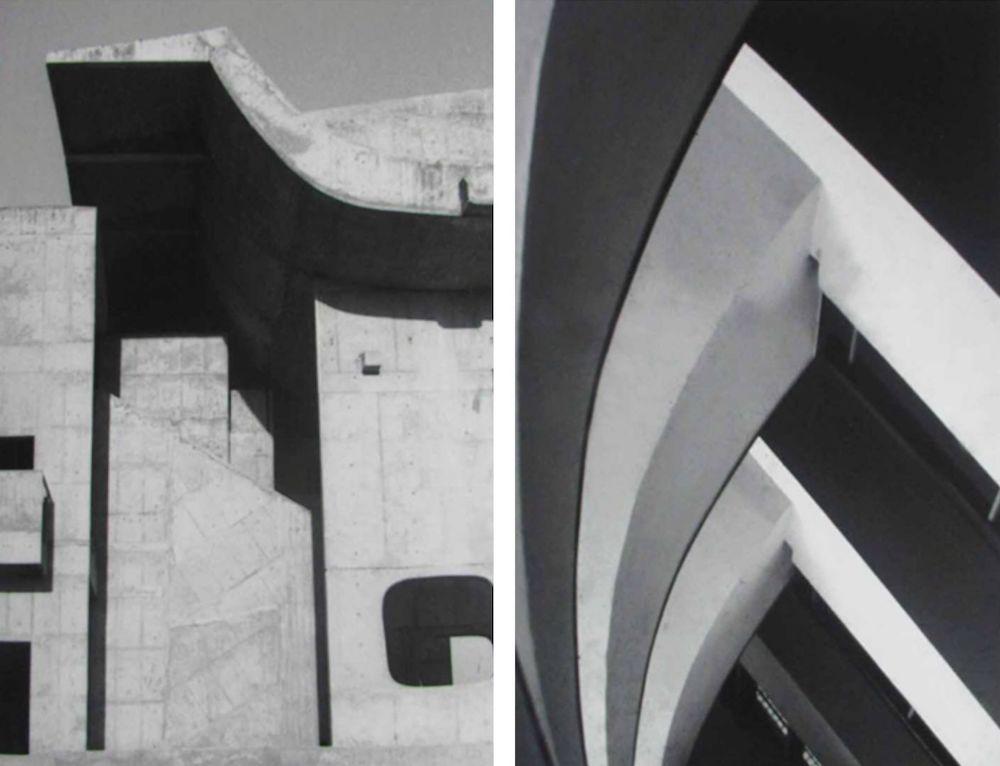

Left: Assembly (Detail 1). Architect: Le Corbusier. (Photograph by Gulammohammed Sheikh. Chandigarh, 1966. Spread from Domus India, October 2020.)

Right: Assembly (Detail 2). Architect: Le Corbusier. (Photograph by Gulammohammed Sheikh. Chandigarh, 1966. Spread from Domus India, October 2020.)

The modernist aesthetic within photography had existed for a while prior to the 1940s—in the clean lines and the highlighting of form through the stark play of light and shadow. However, it acquired new meaning within independent India as it came to be closely linked with architecture and larger discourses of nation-building. In calling attention to this photographic trend within architecture in India, art historian Atreyee Gupta writes in “Dwelling in Abstraction: Post-Partition Segues into Post-War Art”: “This new strand within photography would remain restricted to images of modernist architecture and the industrial landscape, further underscoring the fundamental link between new abstractionist tendencies and the new topographies of postcolonial development that served as its cultural premise and historical ground.”

In this continuing discussion on modernist architecture and photography, we look at the photographic work that followed Jeet Malhotra and his photographs of Chandigarh. Populating these images—with the architects and photographers linked to them—allows us to examine how this shift in trends may have influenced the contemporary generation of photographers.

In 1966, responding to an open position at the Government College of Art, Chandigarh, Gulammohammed Sheikh along with Bhupen Khakhar arrived in the modernist city. Known mostly for his paintings, Sheikh went on to create a series of photographic images on Chandigarh with a focus on the Legislative Assembly building. The images are a combination of close studies of architectural details as well as the entire building. It is interesting to see how the triangular forms present in Malhotra’s images are replicated in a similar fashion within Sheikh’s photos. These images were recently included in the Building Biographies exhibition held at the Guild Art Gallery, Mumbai in 2020.

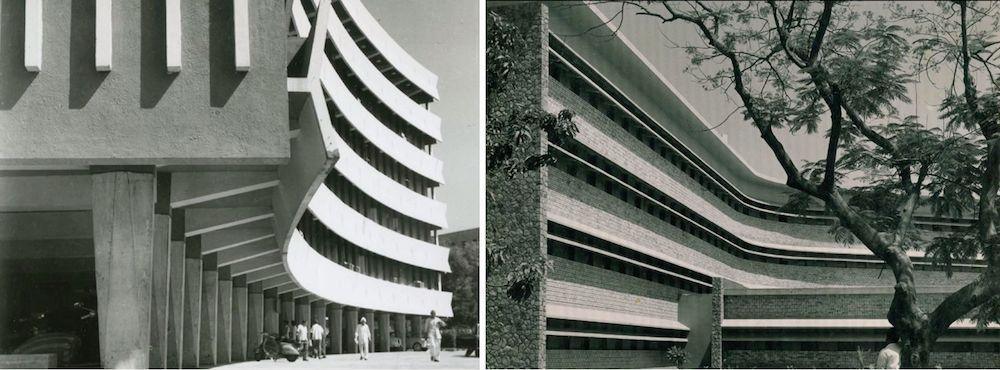

Left: Sardar Patel Bhawan, a Government Office Building. Architect: Habib Rahman. (Photograph by Habib Rahman. New Delhi, 1967.)

Right: The Exteriors of Rabindra Bhawan. Architect: Habib Rahman. (Photograph by Habib Rahman. New Delhi.)

Moving beyond Chandigarh, there was a similar shift towards the building of new modernist structures by architects who had been trained abroad. In New Delhi, Habib Rahman—the architect behind the Rabindra Bhawan, World Health Organisation headquarters and the Dak Bhawan, among others—took up the camera to photograph his buildings. In a 2015 lecture with the C-MAP Asia group at the Museum of Modern Art, his son, Ram Rahman—also an acclaimed photographer of architecture, among other things—presented many images from the 1950s and 1960s of modernist architecture in India. What becomes evident in this series is a similar emphasis on the architectural form. Rahman’s lecture features several images by his father and also includes the work of Madan Mahatta.

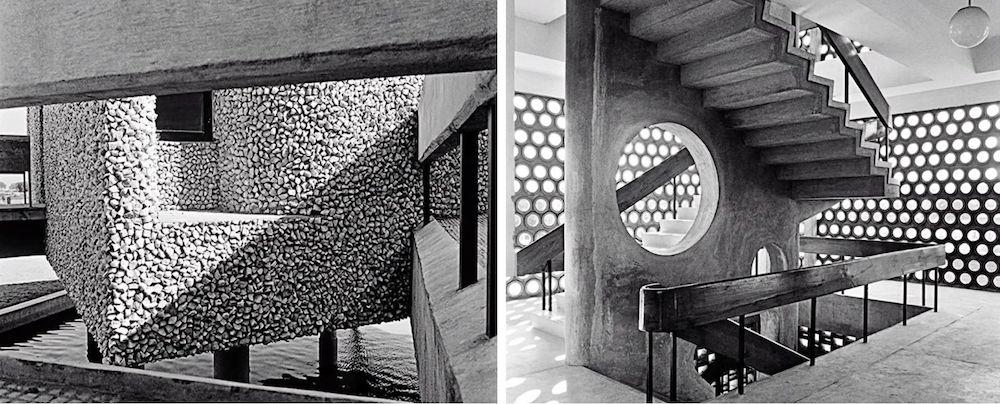

Gandhi Memorial Bhavan. Architect: Achyut Kanvinde. (Photograph by Madan Mahatta. Delhi, 1965.)

Through the range of Mahatta’s oeuvre—capturing the works of architects like Achyut Kanvinde, Joseph Allen Stein, Raj Rewal and others—one is almost able to grasp, in its entirety, the tide of modernism that had swept over Delhi. In 2012, an exhibition of Mahatta’s images curated by Rahman was presented for the first time as a body of architectural photography at the PhotoInk Gallery in New Delhi. Another exhibition held at the same venue in 2020, showcased his images from the late 1960s, of the Indian Institute of Technology in New Delhi designed by JK Chowdhury. In an essay within the accompanying publication, architect and writer Riyaz Tayyibji writes,

“It was the early modernist architectural projects of independent India where the geometry of the line, the plane and orthogonal massing expressed themselves. These seem like vectors shot out of a fractal cacophony of the bazaar into the empty space of that green-field site so intrinsic to the perception of that moment of modernity.”

Interiors of IIT Delhi. Architect: JK Chowdhury. (Photograph by Madan Mahatta. Delhi, 1960s.)

Coming from a family background of studio photography (Mahatta and Co. Studios were present in cities like Delhi, Srinagar, Murree and Rawalpindi), Mahatta studied photography in England. He returned to Delhi in 1955 and thus, was able to capture the wave of new modernist architecture as it rose. Similar to Malhotra, Mahatta was interested in the process and the environments into which these buildings were being constructed. But in the purely artistically inspired moments, he maintained the modernist emphasis on form and geometry. This could be summarised as the essence of modernist photography at the time, as art historians Nathaniel Gaskell and Diva Gujral write in Photography in India: A Visual History from the 1850s to the Present:

“We acknowledge that modernist photography at this time (1950–70) can encompass two broad areas: on the one hand, photographs that themselves display a certain level of abstraction, an attention towards shape and line; on the other, practices that were preoccupied with capturing sites of modernity in the new nation on camera.”

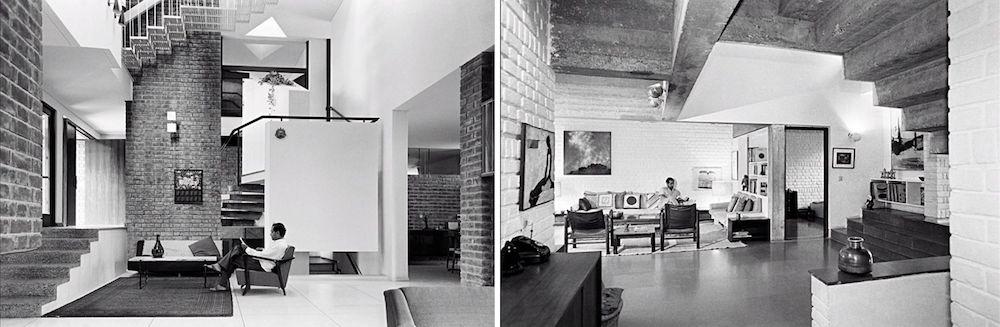

Commissioned by architects, another part of Mahatta’s practice included photographing them in their own homes—which were themselves a reflection of the time’s modernist aesthetic. Not just limited to architecture, these photographs also captured aspects like furniture and home decor, that showcased the work of artists like Riten Mozumdar.

Left: Interior of Achyut Kanvinde’s Residence. Architect: Achyut Kanvinde. (Photograph by Madan Mahatta.)

Right: Interior of Ram Sharma’s Residence. Architect: Ram Sharma. (Photograph by Madan Mahatta.)

These images by Mahatta and others also captured the slightly fantastical, new-age sentiment of watching these modern structures mushrooming in seemingly barren lands. Thus, reflecting back, the period marked a true confluence between photography and architecture, with the aesthetics of one flowing into the other. Both also offer unique forms of documentation that can be productively and independently analysed through an art historical lens.