Annotating a History of Photography: Reading Jyoti Bhatt’s Archive

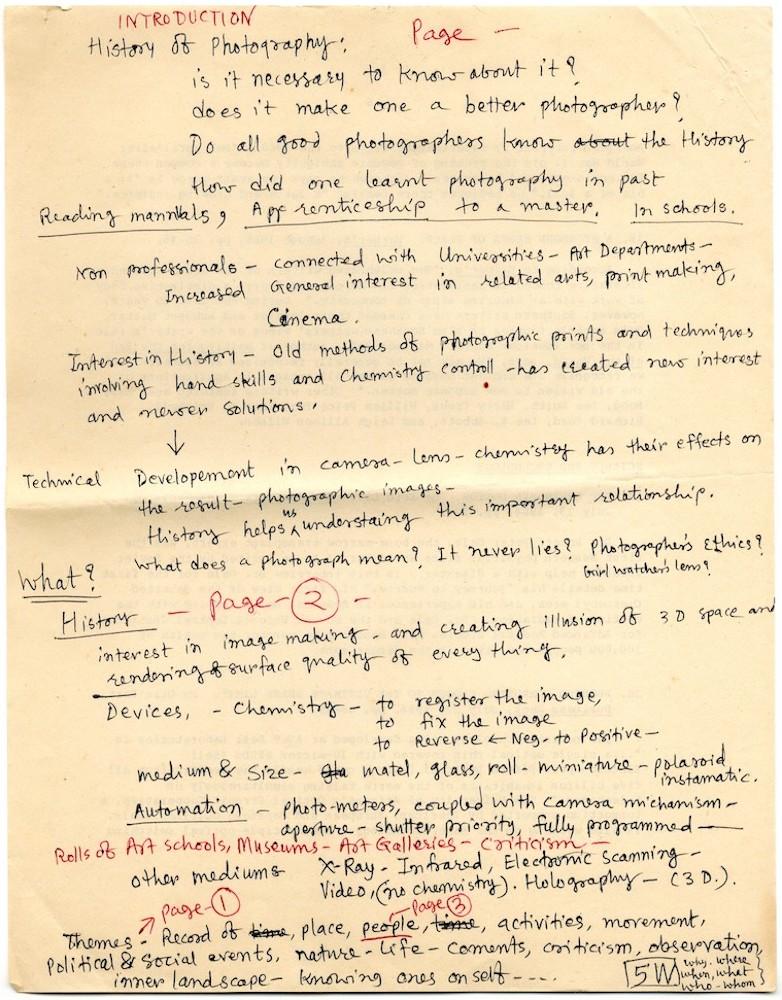

A handwritten manuscript titled Introduction: History of Photography in the modern artist Jyoti Bhatt’s archive begins with a series of questions: “Is it necessary to know about (the history of photograpy)? Does it make one a better photographer? Do all good photographers know the History?” The document contains notes that dwell on the processes of teaching and learning photography. It also provides a broad sweep of the medium’s history: beginning with how eleventh-century Arabian scientists/philosophers amused themselves with camera obscuras made out of tents, to the experimentation in European photography in the 1930s.

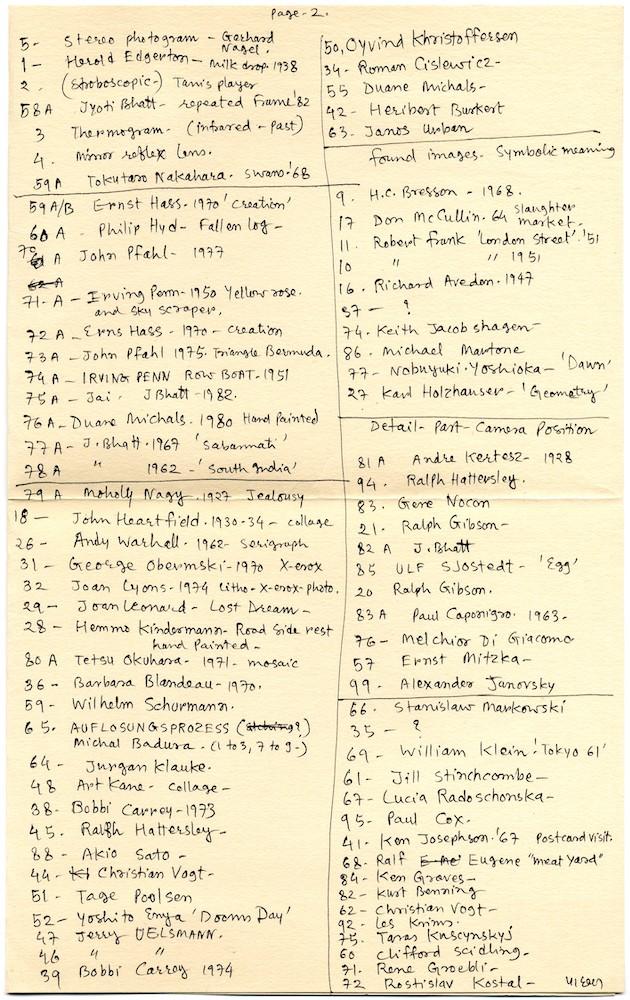

Page from a manuscript by Jyoti Bhatt titled Introduction: History of Photography.

It appeared initially that these were teaching notes, dated approximately to 1985. However, Bhatt himself is not entirely sure about them—they could be preliminary notes for a talk to a group of photo-enthusiasts, for an article, or put together for his own reference from books or a lecture. This piece puts forth some initial prompts on reading the slippery location of such a document—how these fragments can reveal the explorations of an ardent student and teacher of the medium of photography; what his circles were reading and referencing at a certain moment; and the potential of reimagining such a document in the present.

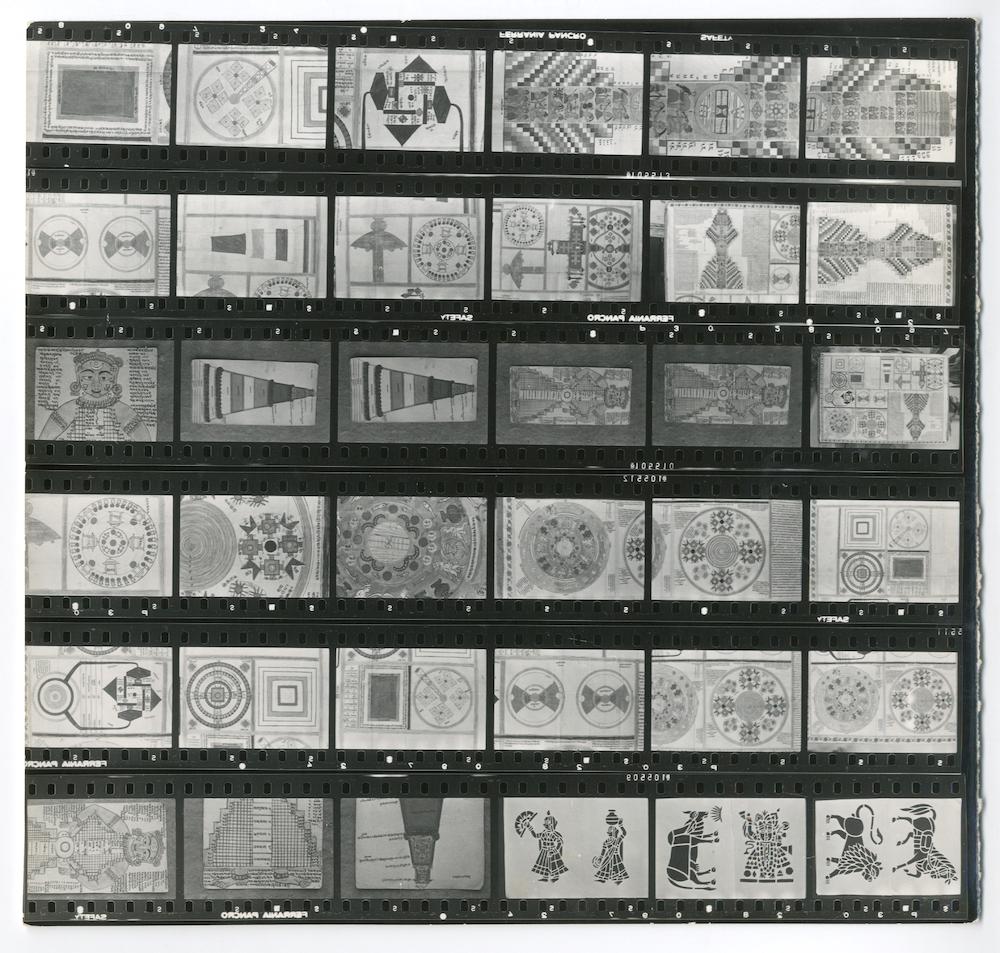

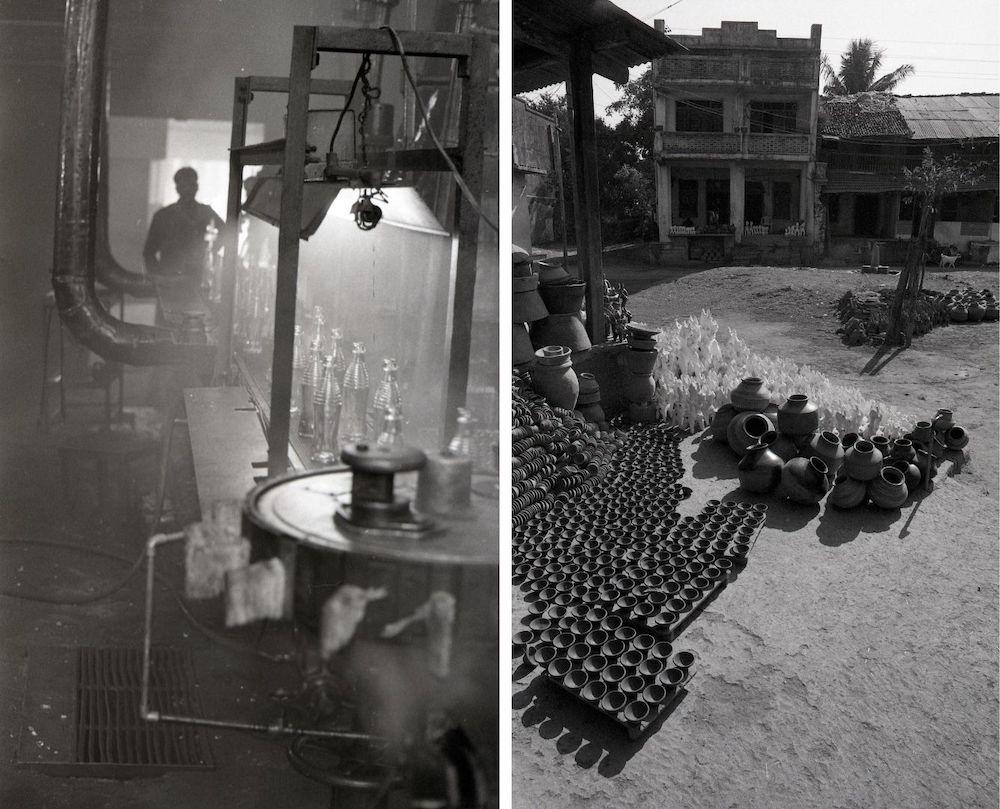

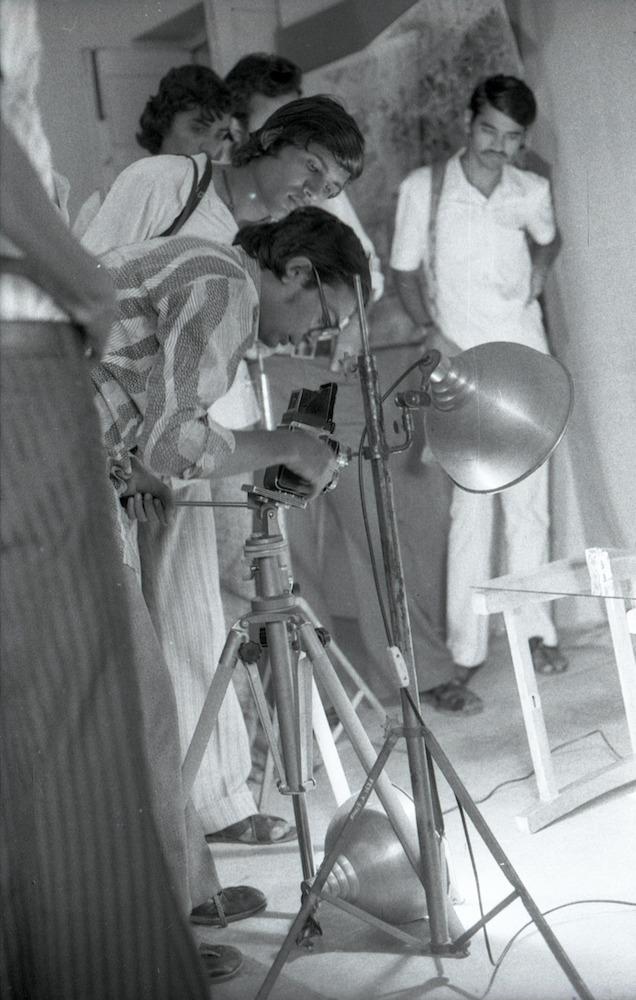

Jyoti Bhatt (b. 1934) is a Vadodara-based painter, printmaker, photographer and art educator. He was part of one of the first batches of students to graduate from the Faculty of Fine Arts at the Maharaja Sayaji Rao University of Baroda, and subsequently taught there for much of his life. His personal archive—digitised by Asia Art Archive—is composed of travel diaries, sketchbooks, designs, writings and artwork documentation, as well as the photographs captured by him over three decades beginning in the 1960s to document the “Living traditions of India.”

Tantric Pat Paintings. (Gujarat, 1969. Contact Sheet.)

Adivasi Rathwa Marriage, Virpur-Samadi. (Gujarat, 1982.)

Bhatt’s role as a teacher shaped his practice. This is visible in the manuscripts and diaries in his archive which record the investigative questions he was asking of the variety of mediums he worked with—both materially and formally. His deep investment in photography is evident not only in the volume and intensity of his actual documentation of rural environments, but also in his writings. Through these, he reflects on the language of photography; its potential as a graphic medium; its relationship to printmaking and painting; and the complexity of documenting “Indian” art forms and the community lives and ritual practices that surround it. As one of the key teachers within the Fine Arts Faculty that espoused photography, and given the manner in which his work focuses on the South Asian region; the document is interesting in its emphasis on a particularly Western history, centred around male photographers. It makes one wonder how the medium and knowledge of its global history was wielded by Bhatt and his colleagues to address the concerns and urgencies of the region.

Left: Alembic Glass Factory. (Vadodara, 1969.)

Right: Bajipura and Valod. (Surat, 1999.)

The document itself is in point form, with markings in different-coloured pens. It gives an outline of the camera apparatus, touching upon shutter-speed, aperture and the chemistry behind the (analogue) process. An ambitious mapping, the document moves from William Henry Fox Talbot’s photogenic drawings to daguerreotypes in the nineteenth-century; from Leonardo da Vinci’s sixteenth-century “Dark chamber” experiments to the emergence of photo-journalism in the twentieth-century with the two World Wars; and from the legacy of the rational, functional experiments at the Bauhaus to the American photographer Diane Arbus’ highlighting of marginalised histories through photography. The document is an all-embracing attempt at introducing and locating the photographic medium in its dispersed lineage, and to understand the history of the medium through a questioning approach—from the point of view of a practitioner.

Photography Lesson at the Department of Applied Arts, Faculty of Fine Arts, Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda. (Vadodara, 1975.)

At the end of the document is a short booklist and an extensive list of images referenced (perhaps to supplement the lecture/notes through examples). It is worthwhile to consider his references as a way to understand the global trade circuits and aesthetic currents of that time. These would have influenced the work of documentary photographers like him, who went on to explore and teach the medium in this (broadly South Asian) regional context. And yet, bearing in mind the expansive ways in which photography has flourished in the region, and the research that has foregrounded diverse visual vocabularies, the questions raised by Bhatt in the document prompt an entirely new set of questions in the present—what else would be read and looked at in a gathering of photo-enthusiasts or students of the medium currently? What connections would be made between the camera obscuras in eleventh-century tents to the digital schemas of today? What would such a document on the history of photography look like now?

Page from a manuscript by Jyoti Bhatt titled Introduction: History of Photography.

All works by Jyoti Bhatt. Images courtesy of the Jyoti Bhatt Archive, Asia Art Archive.