Landscapes of Loss: Retelling the Marichjhapi Massacre with Soumya Sankar Bose

In a short essay titled “Stories” in Understanding a Photograph (2013), John Berger writes of the “inevitable ambiguity” of images that certain narrative forms—primarily, stories—cannot avoid. With the still image, the narrative form reaches to remember what happened. In close association with the field of memory, the photograph begins to shape what Berger refers to as its “…own form of simultaneity.” To this, he asks: What does it mean to assert a sequence of images as a story? What is the photographic narrative form?

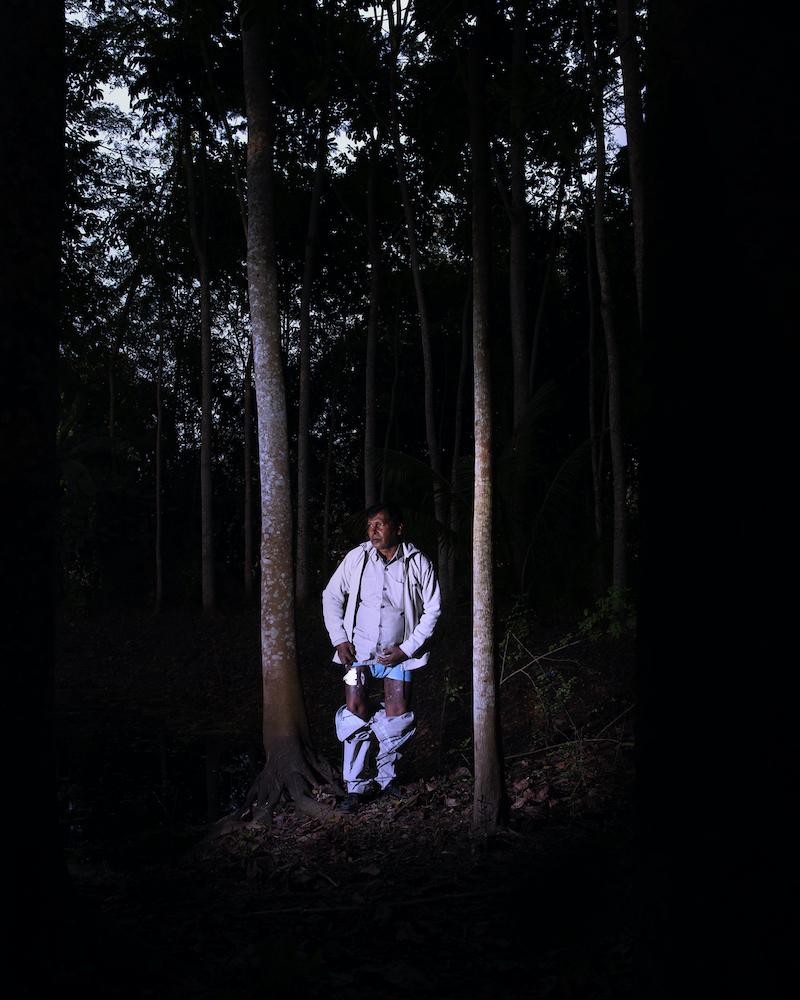

Bokul Majhi. (Rashpur, 2018.)

Soumya Sankar Bose’s photographic project Where the Birds Never Sing centres on the forgotten massacre of several hundreds of Dalit refugees by the Left Front in West Bengal’s Marichjhapi in 1979. Following a physical geography of displacement along the more intangible paths of memory and trauma, Bose’s process assimilates routes to his own past. Helmed by this curiosity, his work explores the event and its aftermath through different narrative formats. This project becomes even more relevant when silhouetted against the introduction of the discriminatory National Register of Citizens (NRC) and the Citizenship (Amendment) Act (CAA) in 2019.

Bose was first introduced to an oral history of the massacre through an earlier project he undertook in 2011 to document Jatra artists. Following this perfunctory encounter with the event, he started to read about the existing narratives around it—including its representation in anthropological research as well as historiographic and fictional literature. He was also drawn to the annual features that appeared in Bengali newspapers on the anniversary of the massacre. Linking his desire to retrace his own grandparents' journey from Bangladesh to India with the missing history of the Marichjhapi massacre, Bose began his in-depth research for the project in 2017. He started this process by first tracing the last remaining survivors and recording their stories. Bose's practice is rooted in a yearning to record the passage of time, fuelled by an acute awareness of trauma and loss. Drawn to the potential of anecdotes, he makes images—referring to them, in a Zoom conversation, as “souvenirs”—based on the stories that emerge, fervent remnants of things he wishes to remember.

During his travels Bose heard from so many people that the Sunderban Tigers become man eaters, because after the Marichjhapi massacre, bodies started to drift on the surface of the swampy waters, where tigers scavenged them.

Working towards realising the photobook, Bose photographed dramatised re-enactments at the actual sites of the massacre and its aftermath. He sought to utilise the surface of the photograph to not only invoke the image as a record, but also as a record-maker. The green of the Sunderbans fades into harsh, contrasting black in the photographs. Sun-weathered faces and scarred limbs gleam alongside what seem to be fragments of conversation—that have been interspersed through the book as imagined and real “accounts”—almost as an invitation to listen in. His richly hued photographs of the wet, lush landscape capture the unmistakable silence of a gradual forgetting. Bose has subsequently engendered the creation of an archive: an open weave of material objects and embodied trauma that offers a not-so-subtle commentary on the feeble presence of this history in apex archival institutions. In such an archival remembering, one finds the photograph acquiescing to a (re)writing of history—that is further emancipated by the memories of survivors and the last traces of the event itself.

Marichjhapi Island. (West Bengal, October 2018.)

Spanning formats of the photobook, a video and an eponymous exhibition at Experimenter Gallery, Kolkata; Where the Birds Never Sing (2017–20) is now a triumvirate of remembrance around a conflicted history. Bose believes the book maps the context of the massacre alongside the performativity of his images. It builds a portability of narratives that allow viewers to pause in consideration of what they consume, as they move through the pages. The documentary video that Bose has been working on over the past year was driven by a need to further amplify the voices in the photographs as well as the orality that found its way into the re-enactments. The video is absorbed into the larger project, complementing the exhibition form that assumes an expansiveness. The exhibitionary framework permits viewers a more didactic engagement with the history of the event as well as the characters and settings of Bose's retelling. Beyond such a diversity of encounters, the weight of the past—political, socio-cultural, personal—is embedded into this work, where languages of the audio-visual animate the interstices of truth and fiction.

Samir Samaddar's gunshot wound which he incurred during the firing on 31 January 1979. (West Bengal, January 2020.)

In the stories that it makes visible, Where the Birds Never Sing makes space for a convergence of the past and the present. Asserting that he has long since left a binary of “right” and “wrong” behind, Bose foregrounds a reflection on the power dynamics of identity and belonging in a country that continues to refute the claims of the marginalised. Photographing memories of the Marichjhapi massacre forty years after it occurred, Where the Birds Never Sing speaks of accountability and erasure; the ownership of unwritten histories; and most importantly, the inheritance of grief that remains unarchived in the definitions of borders and nation-states.

Many waited for their missing relatives for months, but they mostly never returned.

All images by Soumya Sankar Bose. From the Series Where the Birds Never Sing. Images courtesy of the artist.