Surveying the Settler: The Neighbour Before the House by Shaina Anand

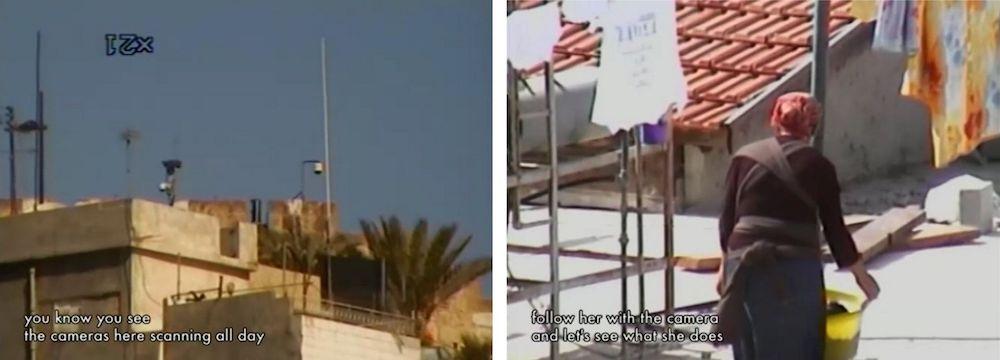

Anand’s film employs a method of ironic role reversal where the Palestinian residents get to operate a surveillance camera and speak about their "settler" neighbours in a way that they cannot hope to do in reality.

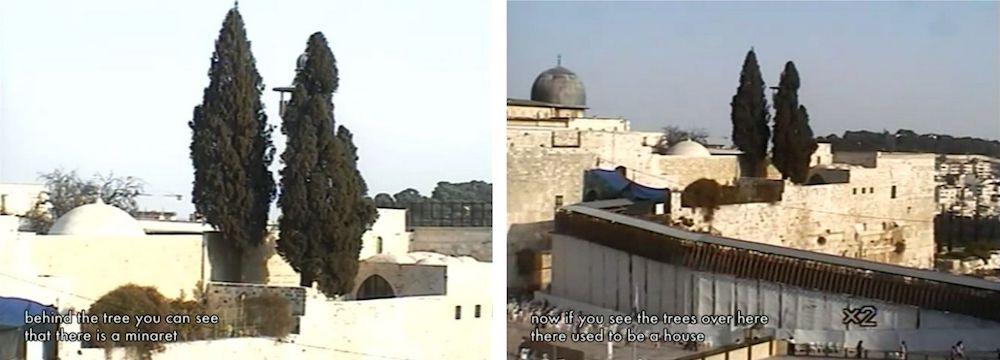

CAMP is a studio founded in 2007 by Shaina Anand, Sanjay Bhangar and Ashok Sukumaran, among others. It seeks to push beyond some of the usual binaries of artistic production and reception, questioning subjects’ relationship to authorship and the role played by technology in producing such discrete fields of authority for a new public. As part of CAMP’s work, Shaina Anand directed Al Jaar Qabla al Daar (The Neighbour Before the House, 2009–11) in which eight Palestinian families are provided with a controllable CCTV camera—whose images are fed into their television—for a closer inspection of their neighbourhoods. Living in neighbourhoods like Sheikh Jarrah, Silwan, Beit Hanina and the Old City of Jerusalem, these families bear witness to the changing political geography. They record settlement activity and how, through its attendant politics of occupation, these areas are taken over—excluding the previous inhabitants who were primarily Arab Palestinians.

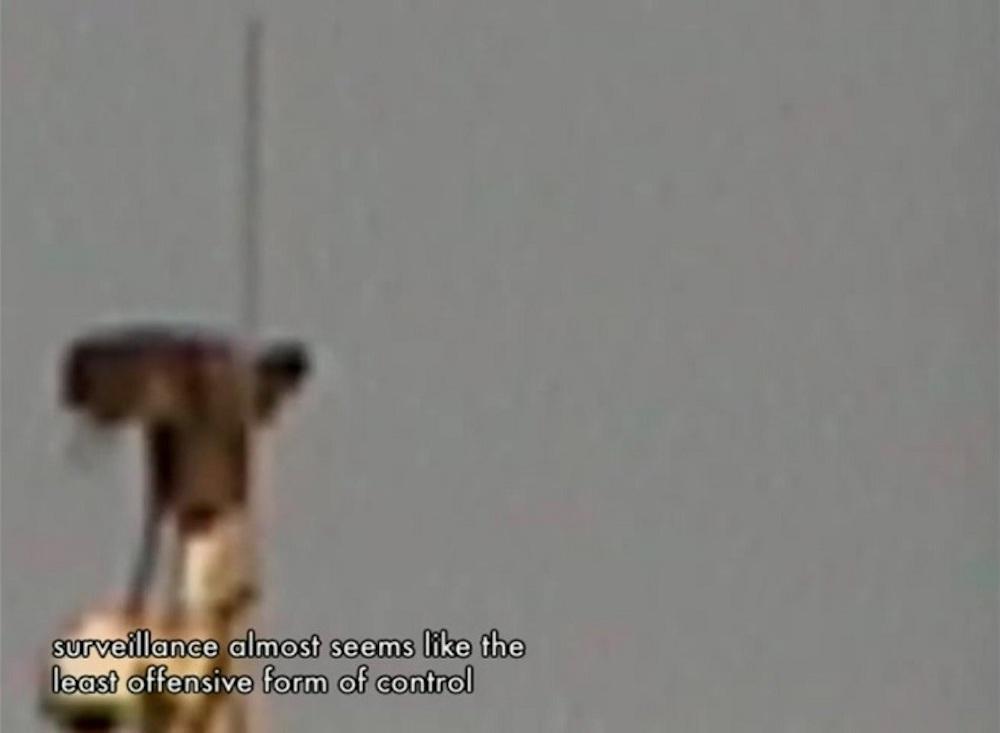

The surveillance camera offers an opportunity to present the landscape as a grid of visibility where elements can be isolated or grouped together. Transforming the landscape into an abstract grid is part of the violence committed by a surveillance state.

The conceit of the film rests upon this ironic inversion of the normative gaze. As one of the most densely secured locations in the world, surveillance cameras are regularly used to monitor and distance the Palestinian inhabitants of these neighbourhoods. They allow the Israeli state to mark their difference from an internal “Other” by keeping them constantly under check. In this film, however, the surveillants have been provided an opportunity to peer across their rooftops and deconstruct the surface of these built neighbourhoods. In doing so, they resurrect old memories of communal togetherness and subsequent tragedies of displacement. The CCTV camera—as unobtrusive as it is ubiquitous—might be the most apt device for capturing this warped, almost infinitely layered, appearance of reality. These cameras are such a regular part of the landscape that the Israeli “settlers” do not seem to suspect their own mock surveillance by these Palestinian families. There is a confidence that the surveillance gaze in the Israeli state belongs solely to the apartheid regime that controls it and produces the power relations in the state.

The camera also offers the Palestinian residents an opportunity for play, zooming into a specific neighbourhood or pulling out to offer a view of the landscape and recognise the changes made to it over time.

The Palestinian watchers discuss the demolishing of old neighbourhoods and the arbitrary laws that are created to control and occupy more space. In lighter moments, they play around with the technology of the camera itself, which allows them a rare, unsupervised look over their own neighbourhoods. The pockmarked landscape reveals the tensions and the barbwires that have separated any possibility of an innocent encounter between the two communities that are living there; an encounter that can provoke what Emmanuel Levinas would recognise to be an ethical responsibility toward “…the face of the Other.” For the security apparatus, which is the greatest aesthetic mediator of relations in old Jerusalem, has successfully reduced the face of this Other to a mass of shifting pixels—a wave of dots on the screen that calls forth no ethical responsibility. The title of the film refers to the Quranic injunction that asks the faithful to honour the rights of neighbourly relations, and it relates to similar ideas in traditions of Jewish and Christian thought too (“Love thy neighbor as thyself,” says Matthew 19:19). As the neighbourhoods become an object of the nightmarish security state, human relations become increasingly abstracted beyond these first principles of community in the holy city.

The Palestinian residents’ vulnerable show of strength consisted of images like these—where a group of old women sitting and chatting outside their houses becomes a radical symbol (the Palestinian flag is painted on the wall behind them) of resistance.

The surveillance camera allows the relatively powerless Palestinian members of the neighbourhood to regain a sense of control over their vision and action. Like a carnival that upsets social relations for a day, this exercise also produces an artificial sense of power, but only for the purpose of this performance.

The mock surveillant’s camera creates a sense of pleasure that is as fleeting as it is unreal, a mere illusionistic trick—like a quick fix.

To read more about Palestine, please click here, here and here.

To read more about CAMP, please click here.

All images from Al Jaar Qabla al Daar by Shaina Anand. Jerusalem/ Al Quds, 2009–11. Images courtesy of the artist and CAMP Studio.