The Sahmat Collective: Art and Activism in India since 1989

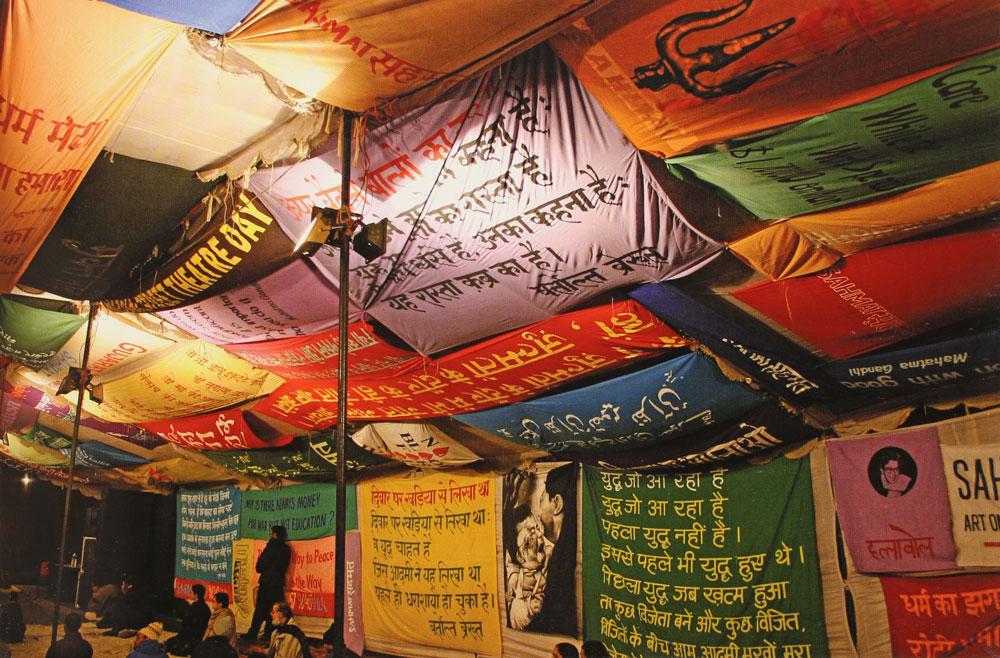

Interior of performance tent, Safdar Hashmi Memorial, The Making of India, 1 January 2004. (In The Sahmat Collective: Art and Activism in India since 1989. By Jessica Moss and Ram Rahman [eds.]. Chicago: Smart Museum of Art, University of Chicago Press, 2013. Image courtesy of the Sahmat Archive.)

The Sahmat Collective: Art and Activism in India since 1989 was published as a catalogue for an exhibition by the same title organised in 2013 at the Smart Museum of Art, University of Chicago. A landmark event presenting an exhaustive survey of the Safdar Hashmi Memorial Trust (Sahmat)’s history and practices since its formation in 1989, the exhibition drew upon photographs as evidentiary and illustrative documents. Writing about the second Johannesburg Biennale curated by Okwui Enwezor, which was concomitant to the truth commissions in South Africa, Clare Butcher in “44 Tonnes” notes how exhibitions concerned with archival investigations hold “…material quality as a messy space of communication, representations, experience, and performativity… any exploration requires more than a classification of lost contents and a published acknowledgment of the politics of the archive.”

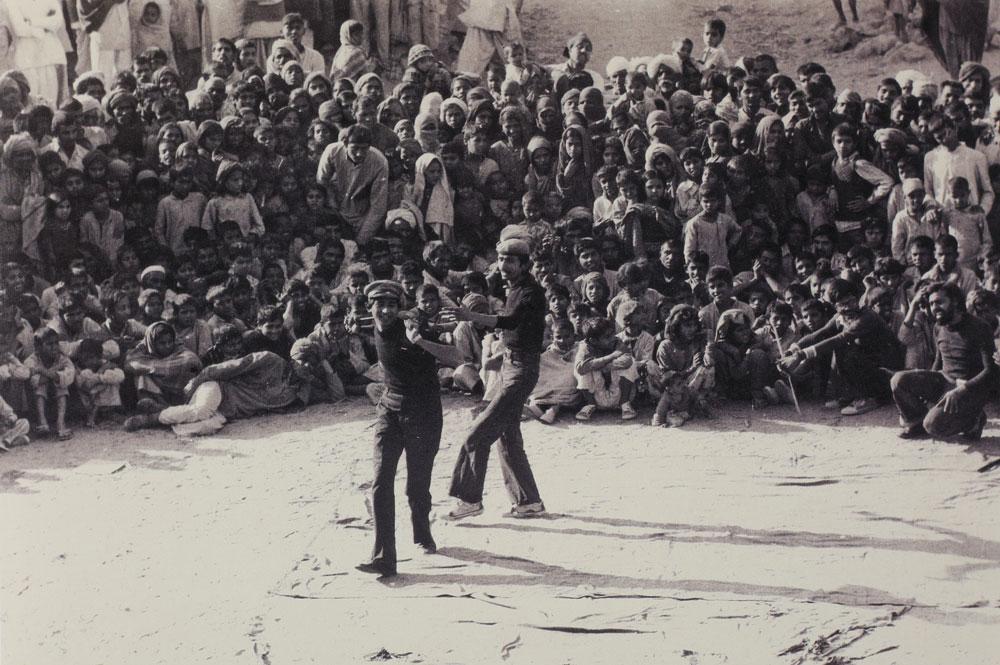

Safdar Hashmi (front) performing in the Janam street play Aaya Chunav (The Elections Are Here), Hissar, Haryana, 1981. (Photograph by Surendra Rajan, In The Sahmat Collective: Art and Activism in India since 1989. By Jessica Moss and Ram Rahman [eds.]. Chicago: Smart Museum of Art, University of Chicago Press, 2013. Image courtesy of Janam archive.)

The exhibition and the catalogue curated and edited by Jessica Moss and Ram Rahman take note of the genealogies that have shaped Sahmat’s approach. While the collective was formed in the wake of a brutal attack on street theatre artists on 1 January 1989, it has since then actively positioned a watchful gaze on the excesses of the Indian state and extralegal agents. Sahmat emerged as an artist-led response to the death of Safdar Hashmi, who was a theatre-practitioner and an activist associated with the Communist Party of India (Marxist). Hashmi co-founded Jana Natya Manch (Janam), a group dedicated to the practice of political street theatre, the roots of which he traced to the performance of Vladimir Mayakovsky’s socialist play Mystery Bouffe in Moscow to mark the first anniversary of the October Revolution; and which he termed as “…people’s theatre in the true sense.”

Janam is committed to actively engaging with contemporaneous realities and with the task of raising political consciousness. They perform in public or open spaces and focus on sites where labourers and working-class persons can watch their plays. In her study of transitions in the modalities of “working-class theatre” in Britain, Kim Wiltshire highlights the difference between the agitprop movement, which went to the labouring classes’ workplaces, and the theatre which followed it, inhabiting the places of working-class leisure. Janam straddled both these domains. Through the 1970s and ’80s, Janam performed in the streets, factories, political rallies, trade union meetings, peri-urban sites, residential areas and resettlement colonies, grounds such as Pragati Maidan etc. In 1989, Janam was performing Halla Bol! (Raise Your Voice!) in an industrial space in Sahibabad—to mark ten days of industrial workers’ strike—when they were interrupted. The performers were attacked by a group which included then member of Indian National Congress, Mukesh Sharma, resulting in Hashmi’s death.

Images and Words carried in procession from Delhi Gate to Safdar Hashmi Marg, Delhi, 12 April 1991. Having an agit-prop aspect, it included works by artists and photographers, and texts by poets and writers—mainly in Hindi, Urdu and English. The display made of bamboo sticks was designed by Orijit Sen and could be easily disassembled and transported. (In The Sahmat Collective: Art and Activism in India since 1989. By Jessica Moss and Ram Rahman [eds.]. Chicago: Smart Museum of Art, University of Chicago Press, 2013. Image courtesy of the Sahmat archive)

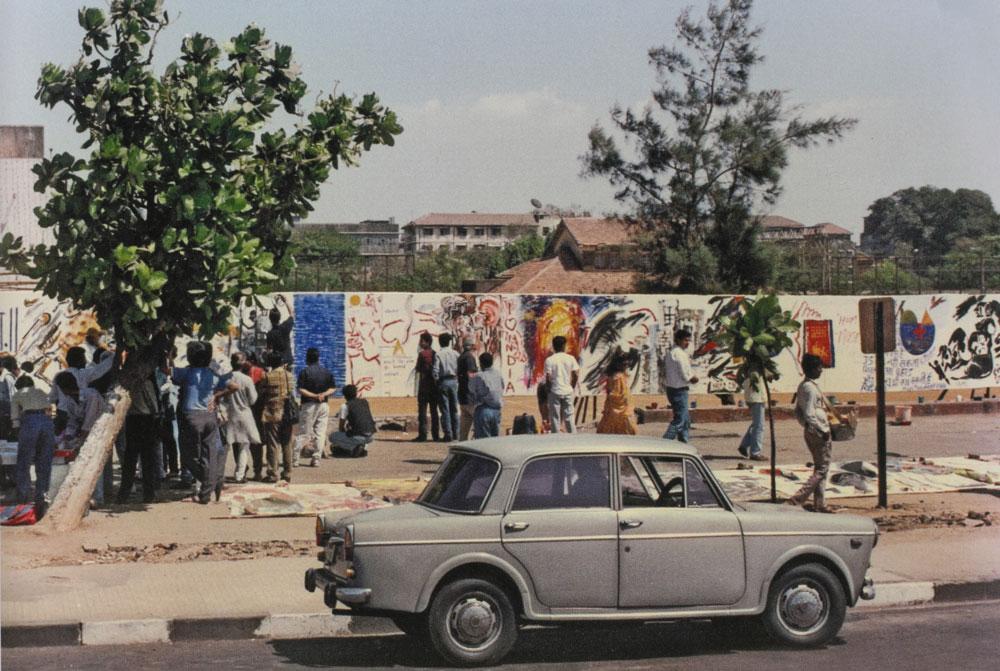

Artists paint a giant canvas on Marine Drive outside the performance venue during Anhad Garje, Mumbai, 20 February 1993. (In The Sahmat Collective: Art and Activism in India since 1989. By Jessica Moss and Ram Rahman [eds.]. Chicago: Smart Museum of Art, University of Chicago Press, 2013. Image courtesy of the Sahmat archive.)

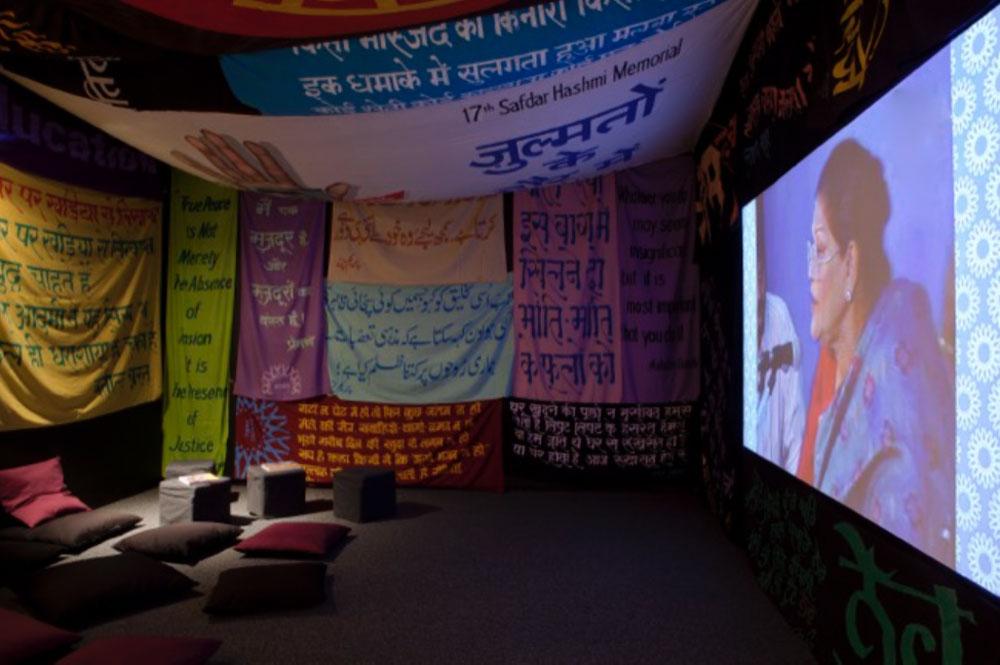

Sahmat emerged as a counter-charge against what Ram Rahman defines as the two-pronged advance of “…right-wing politics in India striving hard to restrict cultural space and freedom from within, and the equally massive assault from the globalised economic and mono-cultural interests coming from the outside.” Its pivotal moment came when it lead an immediate and extensive programme on secularism and religious unity in the aftermath of the demolition of Babri Masjid (1992). From the very beginning, Sahmat adopted a transdisciplinary approach that created hybrid formats of programmes—its annual First of January celebrations brought together concerts, performance art, photography, sit-in protests, symposia and visual art displays. It actively reshaped the scopic conventions and topography of the exhibition space, as posters, pamphlets, cloth banners (media formats of protest) were mounted on temporary tent walls, filling up vertical space with textual excerpts from poetry, slogans, and affirmative declarations towards secularism and egalitarian ideals. These were supplemented with postcards and children’s books based on poems written by Hashmi and illustrated by various artists.

The exhibition Red the Earth on the 1857 Revolt, Delhi, 2007. Displays by Sahmat often utilise bylanes and pavements, and the materials used for advertisement and political campaigning include hand-painted cloth banners, posters and flexi banners. (In The Sahmat Collective: Art and Activism in India since 1989. By Jessica Moss and Ram Rahman [eds.]. Chicago: Smart Museum of Art, University of Chicago Press, 2013. Image courtesy of the Sahmat archive.)

In its quick response to the Babri Masjid demolition, Sahmat actively collapsed the barriers between artistic activism and political art—imbricating the production, display and reception of art with practices of witnessing, recording, and civic dissent against hegemonies of the state. Here, the catalogue’s focus on genealogies is rewarding as one can discern synergies between different groups as an active field of associations and exchanges. Key Communist Party of India members and Indian People’s Theatre Association leaders such as Bhisham Sahni and Habib Tanvir were involved with Sahmat. While Sahmat worked out of and leaned on the organisational resources of the CPI (M) office in Delhi, it remained an independent group led by artists of varied political affiliations. An essay titled “An Experiment with Political Theory” by Prabhat Patnaik in the catalogue dwells on this “dialectics” of autonomy and interdependence between the “party” (CPI-M) and Sahmat. Patnaik claims that spaces such as Sahmat—that invite and thrive on participation by those occupying a spectrum of “progressive” political goals—perform a dual function towards securing the life of resistance. Firstly, these spaces stop the “drift” of those who disagree with CPI-M’s policies away from any political action altogether. Secondly, it permits those within the party to escape the inertia of organised polity and partake in responsive, urgent and immediate action.

Installation view of The Sahmat Collective: Art and Activism in India since 1989 at Smart Museum of Art, Chicago, 2013. The recreation of a Sahmat venue, with the temporariness of a tent and cloth banners, is a noteworthy display and installation strategy—suggesting complex relations between exhibition-making and viewing practices with sites of resistance. (Image courtesy of the Smart Museum of Art and Sahmat archive.)

Installation view of The Sahmat Collective: Art and Activism in India since 1989 at Smart Museum of Art, Chicago, 2013. Note the similarities in the display of artworks in the Images and Words show on temporary props—a mobile, dynamic template explored by Sahmat in 1991 and reproduced at Smart Museum of Art. (Image courtesy of the Smart Museum of Art and Sahmat archive.)

These affinities suggest a complex network of solidarities and kinship, critique and autonomy beyond the ambit of commercial circuits. It also suggests the proximities of lens-based practices and political theatre, as Philip Auslander notes, “The live and the mediatized exist in a relation of mutual dependence and imbrication, not one of opposition” even before the intervention of the photographic image, giving the example of the use of microphone in performances that alters the bodily relations between the performers and the audience. It is interesting to think about the meanings available to us through a primarily photographic and anecdotal record of two organisations—Janam and Sahmat—of narration and memory, document and image as tools to access histories of the recent past.