On Art as Collective Action: An Interview with NayanTara Gurung Kakshapati

NayanTara Gurung Kakshapati. (Photograph by Sagar Chhetri.)

NayanTara Gurung Kakshapati is a force to be reckoned with. Founder of photo.circle, co-founder of Nepal Picture Library and Director of the prestigious photography biennial Photo Kathmandu, she has been instrumental in establishing Kathmandu and (broadly) Nepal as a cultural hub for image-based practices within South Asia.

The curator, pedagogue and activist spoke to Ketaki Varma about the ongoing fourth edition of Photo Kathmandu, the effects of Covid-19 and the festival’s plans for the future.

Ketaki Varma (KV): Since its first edition, Photo Kathmandu (hereafter PhotoKTM) has been a space for visual storytellers across South Asia to come together and engage with an extended artistic community. This year, due to Covid-19, a physical festival was impossible. How did the biennial adapt its infrastructure in response to the pandemic?

NayanTara Gurung Kakshapati (NTGK): PhotoKTM started in 2015, which was a particularly challenging year for us in Nepal—we lost 9000+ lives and much infrastructure in a devastating earthquake. That year, we had felt the need to stage a spectacle that would contribute towards rebuilding hope. Five years and many lessons later, we are feeling the need to switch gears and operate differently. By the summer this year, the entire world was feeling changed due to Covid-19 and it made no sense to run the festival as per a pre-Covid world. We have always wanted PhotoKTM to be relevant, remain manageable, serve local and regional needs, push forward conversations that we feel are important and necessary, and continue to build community and solidarity. For this edition of PhotoKTM, we decided to break out of our five-week festival format and shift to a year-long calendar of virtual engagements.

Programming Banner for PhotoKTM4. (Image courtesy of Photo Kathmandu.)

Screenshot of PhotoKTM4 Mixer, 5 December 2020. The event was a casual gathering of festival attendees to share ideas and contacts for possible future collaborations. (Image courtesy of Photo Kathmandu.)

The festival is part of a larger continuum of image-making, research and civic engagements for us at photo.circle and Nepal Picture Library. We have always asked ourselves—what might be possible if we were to take the resources and energy we commit to our usual festival format and stretch it out over a longer period? Would we be able to foster deeper, less frenzied engagements? We felt this year was a good time to shift gears and find out.

Review Sessions Banner for PhotoKTM4. (Image courtesy of Photo Kathmandu.)

KV: PhotoKTM4’s curatorial framework revolves around the ideas of “assemblage, collectivisation and the commons.” What do you mean by this? How do these ideologies play out in practice?

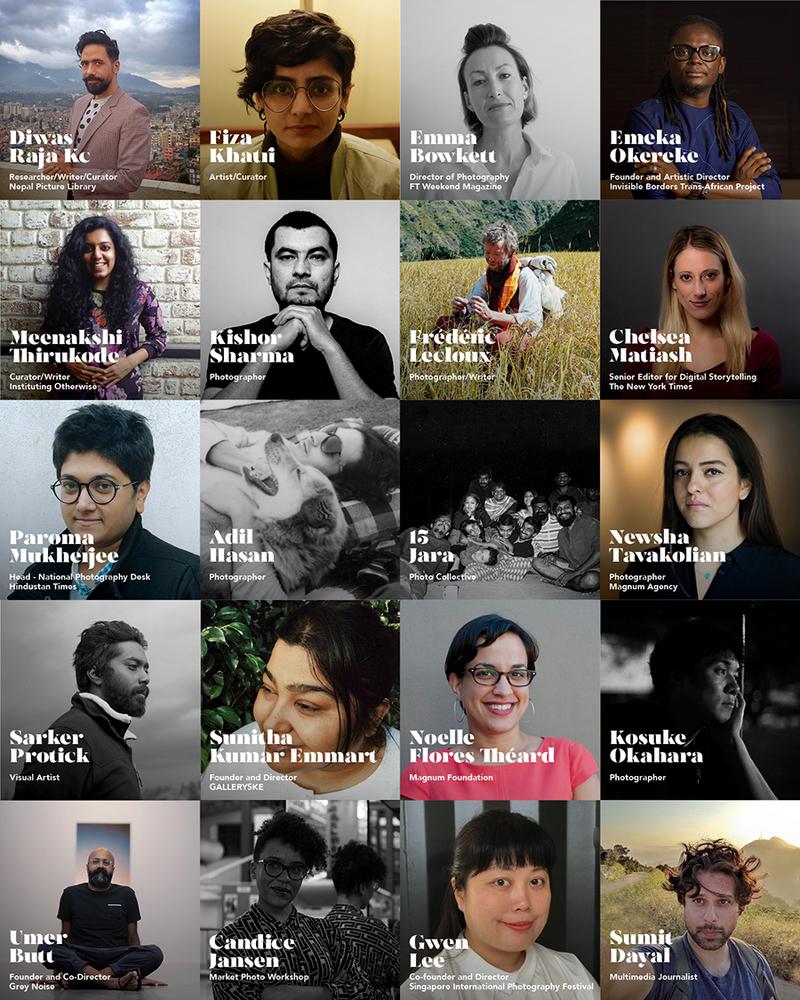

NTGK: The festival is, first and foremost, a coming together of people and ideas. From the very beginning, we have opted for a framework that enables multiple individuals to shape curatorial decisions and visions, and allow an interdisciplinary coming together of thought, medium and practice. PhotoKTM4 has invited Aziz Sohail (Pakistan), Sumitra Sunder (India), and Diwas Raja Kc (Nepal) to bring together practitioners from across South Asia to open up new perspectives on queer art practice and posit them in a regional archive that serves as a site of collectivity, speculation and creation. Through this collaboration, the three curators will look at “queerness” as a category that is faithless to borders and boundaries. The festival will also be providing a platform for the Kathmandu Valley Urban History Project, a public knowledge initiative that examines the rapidly changing landscape of the Kathmandu valley—its built environment, water sources, and ideas around urbanisation, public space, the commons, change and the future. PhotoKTM4, then, seeks to explore assemblage, collectivisation and the commons by unpacking them as ideas but also supporting a variety of collaborative artistic, research and pedagogic initiatives such as the two examples mentioned above.

Nepali photographer Bunu Dhungana engages in a theatre exercise with local women of Khapinchhe in Patan, where her exhibition titled Confrontations was on view at the 2018 edition of PhotoKTM. (Photograph by Chemi Dorje, Kathmandu, 2018. Image courtesy of Photo Kathmandu.)

KV: The idea of collective agency has been a key idea in how you have conceived PhotoKTM. What do you imagine is the future of a space like PhotoKTM? What sort of agency, if at all, does it provide to the art world in Nepal particularly and South Asia in general?

NTGK: I feel the festival will continue to find relevance and purpose in the years ahead only if it can remain responsive to local and regional concerns and priorities. If it can stay light-footed enough to morph into whatever is most useful and exciting at that time and shape-shift when necessary, without getting bogged down by global art world standards and expectations, while staying accountable to the community, then the festival can contribute to defining the contours of our own creative eco-system. That is, perhaps, what it means to have utmost freedom, agency and social responsibility. This is the future I hope for PhotoKTM.

Visual Thinking, a four-day workshop with Katrin Koenning. Each edition of PhotoKTM hosts a series of professional development programs for photographers and artists. (Photograph by Chemi Dorje, Kathmandu, 2018. Image courtesy of Photo Kathmandu.)

Students from a local school visit Tuomo Manninen's exhibition titled We as part of guided tours and other activities offered by PhotoKTM's arts and education program. (Photograph by Mahendra Khadke, Kathmandu, 2015. Image courtesy of Photo Kathmandu.)