The (Un)Making of Memories: Piotr Cieplak’s The Faces We Lost

Adeline Umuhoza holds a framed portrait of her father.

In The Faces We Lost—the award-winning 2017 documentary directed and produced by Piotr Cieplak—Paul Rukesha of the Genocide Archive, run by Aegis Trust in Rwanda, speaks of the incurable affliction of living through the aftermath of the Rwandan genocide. Rukesha says, “A photograph can act as a form of medication. When trauma returns, a photograph can help. It provides comfort and respite.” Remembered primarily through images of violence, the Rwandan genocide is situated as a historical event, within networks of image-making and circulation that iconised the brutalities that targeted and eliminated the Rwandan Tutsis, along with moderate Hutus and members of the Twa minority, lasting for about a hundred days between April and July 1994.

Mama Lambert holds a cherished family photograph taken at a wedding.

The context of the violence in 1994 stretches back—beyond the four years immediately prior to the genocide—to a time when prejudice against Tutsis characterised Rwandan President Juvénal Habyarimana’s regime. The genocide took place against the background of a civil war that had started in 1990 between the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) and Forces Armées Rwandaises. While the two events remained separate, the four years leading up to the genocide were rife with radicalised racial discourse, economic and political instability, and the growing anti-Tutsi sentiment that was fuelled to urge people to self-organise. Rwandan Tutsis were portrayed as RPF collaborators, and the severity of the deaths in the conflicts came to serve as a chilling foreshadowing of what was to come in 1994.

Filmmaker-academic Piotr Cieplak’s first feature documentary, The Faces We Lost, foregrounds the stories of nine survivors and their modes of remembering. These are mediated through the presence—and in more than one instance, the absence—of photographs in both the personal as well professional spaces of memory keeping. Several films on Rwanda have referenced family photographs as tangible objects, but there has been little or no engagement with the relationship of these photographs with the aftermath of the genocide itself. Conversing with the survivors as consumers of the image and not just as documentary subjects, Cieplak situates their subjectivities within the deeply intimate associations they form with the photographs. The photographs themselves span moments of celebration; cherished portraits of parents, spouses and children; treasured passport photographs; and several childhood candids. The film parallels Cieplak’s book published in the same year, titled Death, Image, Memory: The Genocide in Rwanda and its Aftermath in Photography and Documentary Film which allowed him to undertake a more detailed reading of certain images, collections and writings. The project unravels the complexities of media—photographs and documentary film-making—in methodologies of critical research around modes of remembering and representing the genocide in Rwanda.

The memorial at the Ntarama Church, a site of massacre.

The representation of suffering that photographs of violence instantiate is a double-edged sword. Such images constitute necessary elements within the politics of visuality today, but they are also easily appropriated and require active citations to maintain a legibility around their contexts. The last two years in India have converged into a timeline of eruptions protesting against the extremist communal state. The archive of images produced during this period—photojournalistic and otherwise—typify a violent (un)making of personhood and belonging. The imminent ethnic dismantling and the continuous dehumanisation of citizens is evident across these images—especially the photographs from protest sites across the country—in their documentation of what are evidently acts of state-sponsored violence against the right to dissent. Years after the Rwandan genocide, grief is palpable and mourning is a continuing state in families that lost generations of loved ones to the violence. Yet, global representations of the suffering and horrors of the violence are veiled by an aesthetic that is entirely disengaged from the implications of uncritical memorialisation.

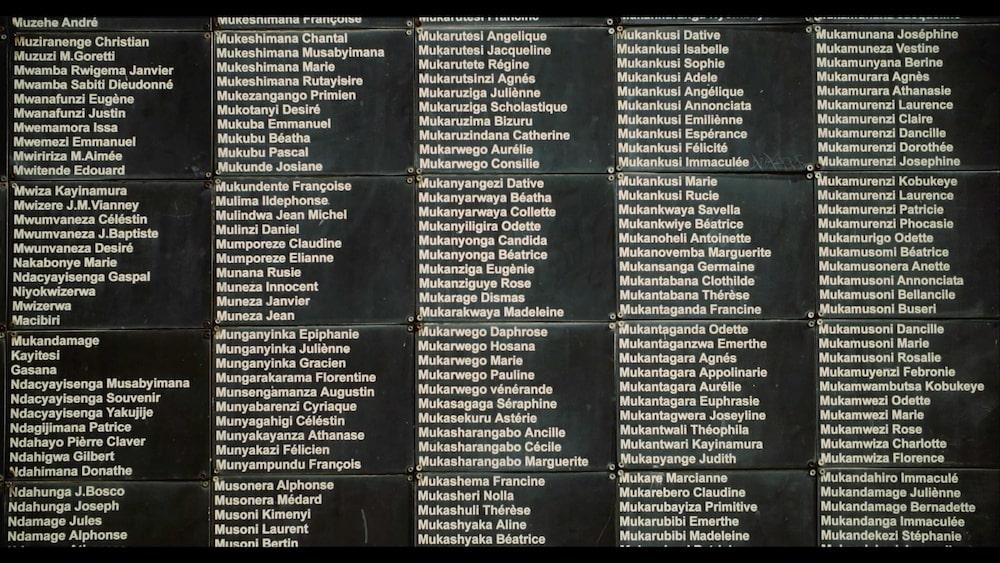

Names of victims of the genocide at the Genocide Archive of Rwanda.

The episodic violence of Rwanda’s early years of independence—and the years of the social revolution (1959–62) preceding it—as well as the discriminatory agenda of Habyarimana’s regime and its furthering of anti-Tutsi sentiment in the years building up to the 1994 genocide can be traced to Rwanda’s colonial past. Following its independence from Belgium in 1962, Rwanda witnessed the exodus of several thousand Tutsis and the first organised slaughter of Tutsis who remained in the country. While differences between Hutus and Tutsis existed before colonisation, it was the Belgian colonial authorities who reified previously fluid categories of clan politics into divisive brackets. Ethnicity was decisive in Rwandan politics, and while Belgium initially favoured the Tutsis, it eventually switched allegiances. By 1962, it left behind a wounded social fabric and a deep-rooted vengefulness that marked Hutu-Tutsi relations.

In the introduction to his book, Cieplak writes that while the victory of the Tutsi-dominated Rwandan Patriotic Front in July 1994 reinstated a semblance of control, its facade of relief came too late for the victims of the multiple massacres. Studying the domesticity of associations that these survivors cultivate with the photographic, Cieplak’s film underscores the photograph as a record of both life and death. Several of the survivors in the film blur the line between representation and actual presence, placing the photograph in a spatio-temporal functionality that mediates, consoles and mitigates the traumatic recollection.

To read more about The Faces We Lost, please click here.

All images from The Faces We Lost by Piotr Cieplak. 2017. Images courtesy of the artist.