Remembering in Rwanda: The Sanctity of the Aftermath in The Faces We Lost

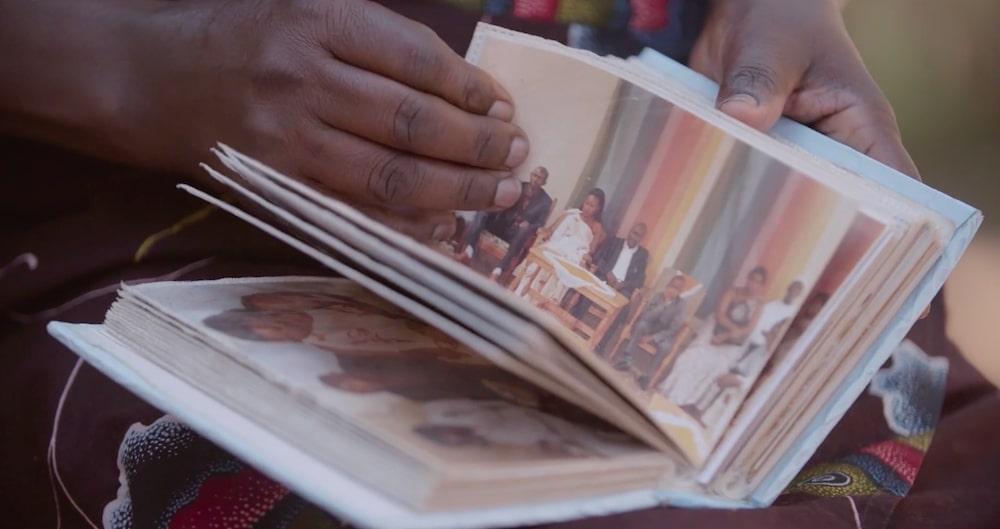

Oliva Mukarusine looks at a carefully preserved album of photographs as she speaks about her husband.

The downing of the plane carrying Rwandan and Burundian presidents, Juvénal Habyarimana and Cyprien Ntaryamira respectively, on 6 April 1994 is widely seen as marking the start of the Rwandan genocide. While the plane's destruction was a catalyst, the genocide itself was not a spontaneous combustion of violence and murder. The complexity of such a narrative disrupts the annals of history, especially in the manner in which the linearity of historiography fails to take into account the imbrications of perpetrator, executor and victim. Taking the intimate route of personal memory in its effort to document—and insert a layering into—the aftermath of the Rwandan genocide of 1994, Piotr Cieplak’s documentary The Faces We Lost (2017) follows nine Rwandans (genocide survivors, relatives of the victims and professional archivists) as they speak of their memories of loss and death. These narratives are mediated by the role of priceless family photographs, in a present that continues to anchor them to the past.

Cecile Mutabonwa’s collection of family photographs.

In the documentary, Cieplak highlights the family album as an object retrieved from obliteration and as simultaneously retrieving memories. This presents a narrative possibility to genocide survivors like Cecile Mutabonwa and Oliva Mukarusine who are able to identify photographs through the people they represent. Living alongside not just a memory but a severe physicality of loss, Claudine Mukantaganzwa experiences the bereavement of her husband and other family members twice over in the absence of any photograph by which she can remember them. Mukantaganzwa’s daughters, who also feature in the film, remember their father through associations they seem to have formed via a maternal inheritance of orality and imagination. Cieplak’s juxtaposition of these various narratives of the survivors and their photographic possessions are transformative. The film lingers on how the affective objecthood of these images allows for reminiscence, healing and a retracing of filial belonging within these families.

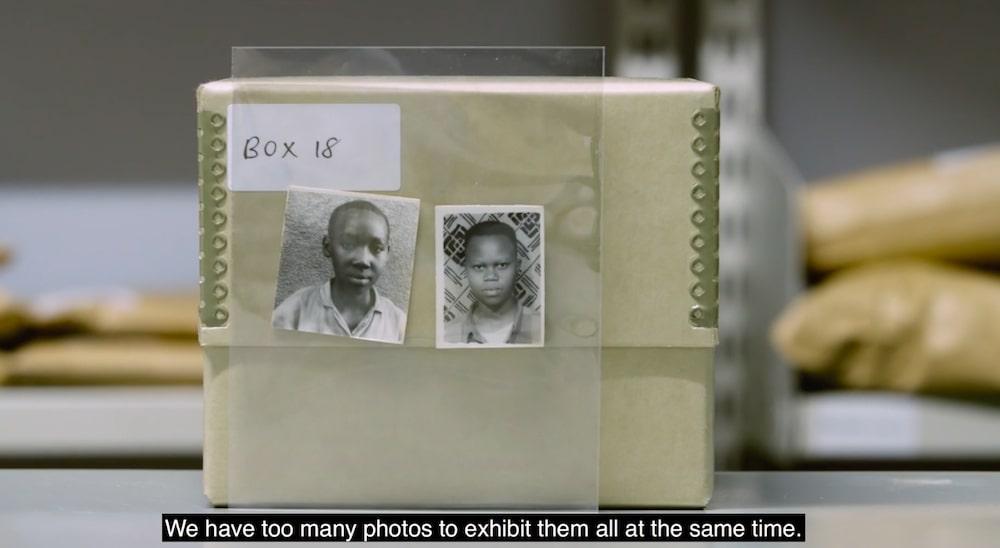

Photographs in archival storage at the Genocide Archive of Rwanda.

An important parallel that Cieplak draws is between the two kinds of spaces of remembrance portrayed in the film, namely the personal located in the homes of the survivors, and the professional ambits of two institutions, namely the Genocide Archive of Rwanda and the Kigali Genocide Memorial. At this intersection of the public and private, memory becomes an indelible link between the mass graves that occupy the same premises as the archives that preserve these photographs. Priceless as these photographs are to the families of the victims, a number of survivors submit them to the archive for safekeeping. As memorial institutions, these spaces come to contain and protect the traces of a collective remembering around a shared loss. Through their own intuitive vocabulary, the memory-keepers in these archives—Claver, Aline, Serge and Paul—focus on being able to build and sustain connections with each photograph that they encounter, refusing to let victims of the genocide remain mere statistics on a graph.

Photographs on public display at the Genocide Archive of Rwanda.

Reactions and responses from the international community were slow on the uptake during and after the genocide in 1994. This is a tendency that Cieplak highlights in his book Death, Image, Memory: The Genocide in Rwanda and its Aftermath in Photography and Documentary Film, as he points to the reluctance and refusal to use the legal term “genocide.” Even in April 1994, at the height of the killings, the United Nations Security Council did not do so, despite the presence of overwhelming evidence. Following the passing of the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) in India in December 2019, concerned citizens took to the streets in record numbers to express their displeasure with the law. In February 2020, the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) threatened protesters in North-East Delhi. Violence erupted soon after, killing fifty-three people—the bulk of whom were Muslims—injuring 250 others, displacing a total of 2,000 people. The state and media were quick to label this violence as a “riot.” However, the term "pogrom" offers a more accurate description of the inherent systematisation at hand, implying state participation. In the scripting of a narrative, the legalities that define an act of violence often abdicate culpability, and the hesitation in identifying the premeditation inherent in a pogrom—or a genocide—is also aimed at desensitising the act of witnessing as a collective.

Adeline Umuhoza looks at a photograph of her father on her phone.

The memorialisation of the event, a crucial part of Rwanda’s post-genocide life, is complicated in its aftermath. The presence of these archives in Rwanda also prevents a forgetting; the memory of the genocide is an intense, unbearable perpetuity and these archives firmly disallow any passivity and indifference to exist. The archives are now working to expand into the digital domain in order to maintain the connections that are forged between people sharing their stories and those who seek a glimpse of the familiar within them. They are prioritising a counteracting of denial, and subsequently, problematising the spectacularisation of such histories across media. This is especially relevant as the Rwandan government faced sharp criticism for its politicisation of the genocide as a means of retaining power in the country. Zoe Norridge writes in a review of the film, “The Faces We Lost is extraordinarily gentle,” centralising the agential in the stories of these survivors. Mama Lambert, one of the survivors in the film, inscribes a photograph of her friends in Kinyarwanda, “Ndabibuka nkagira intimba (I remember you and feel pain).” In a similar frequency, Cieplak engenders a mode of listening in the film that invites viewers to witness the palliative affirmations that guide sentiment and the making of memory in Rwanda.

Mama Lambert’s inscription around a photograph that states, “Ndabibuka nkagira intimba (I remember you and feel pain).”

In case you missed the first part of this post, please click here.

All images from The Faces We Lost by Piotr Cieplak. 2017. Images courtesy of the artist.