Between Image and Text: Reading Malavika Karlekar’s History of Early Photography

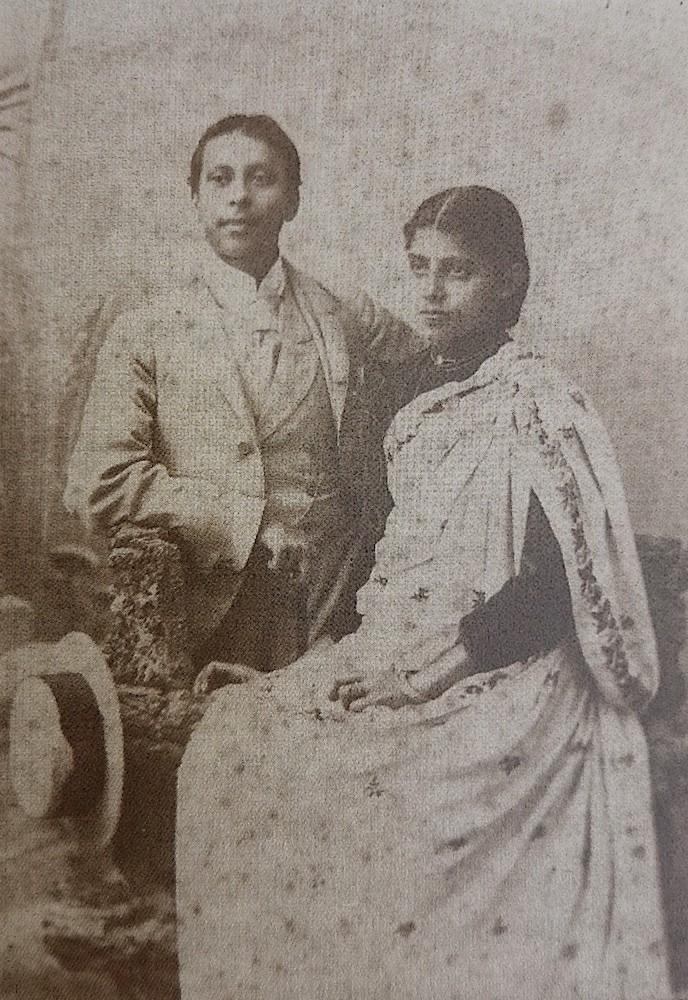

A young Rabindranath Tagore, seen here with his ten-year-old bride, Mrinalini. Taken at Bourne and Shepherd, this picture also represents a type of the conjugal photograph that glossed over—without really concealing—the vast gulf of differences in age, background and intellectual maturity between the two. (Image courtesy of Rabindra Bhawan Photo Archives, Visva-Bharati University, Santiniketan.)

Malavika Karlekar is a historian and anthropologist, specialising in nineteenth-century women’s histories in India, often with a focus on Bengal. Her book, Re-visioning the Past: Early Photography in Bengal 1875–1915 (Oxford University Press, 2005), is an account of the early years of photography from the perspective of those disciplines. This book is a revised version of the report Karlekar submitted to the India Foundation for the Arts as part of a two-year Arts Research and Documentation grant. Explaining the use of the photographic material in her book, she contends that its job is not to provide a litany of “pretty” supplements to written accounts of the same past. Rather, she writes,

“I argue ’reading’ photographs is to introduce another dimension to the experience of colonialism in Bengal. The focus is on how the photograph intervened in the lives of the landed elite and the growing middle class who had made their homes in and around Calcutta seen against the backdrop of colonialism and its increasing use of the visual.”

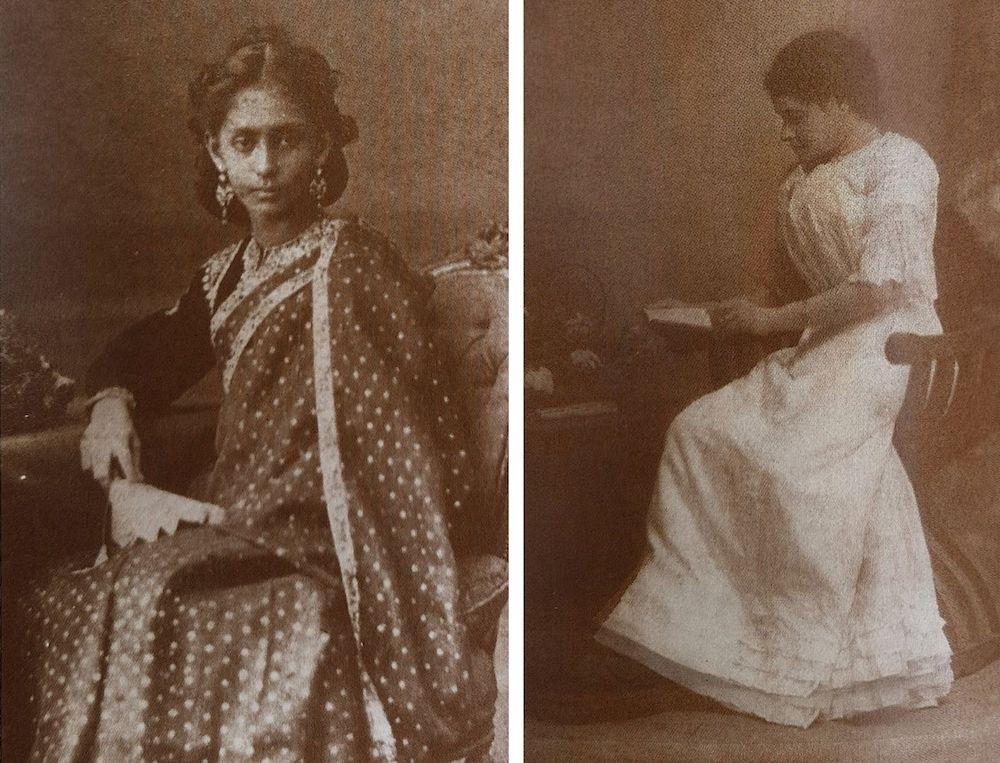

Protibha Debi (left) and Indumati (right) were granddaughters of Debendranath Tagore. Photographs of unmarried women were rare; so, in pictures like these, they occupy their "primary role" as wives of socially significant men. Indumati wore a gown while Protibha Debi was dressed in her fashionable best—with a fan, an elaborate coiffure and long earrings—before a social occasion. Being fashionable thus became a way of distinguishing oneself in public. (Images courtesy of Rabindra Bhawan Photo Archives, Visva-Bharati University, Santiniketan.)

The narrative of the book is largely confined, therefore, to erstwhile Calcutta of the late nineteenth-century (and a few of its suburbs where studios were set up)—where the photographic studio became a charged site of the colonial encounter with self-fashioning practices. Apart from the wide number of colonial officials and their family members, the first human subjects of these early studios were the local people of Bengal. Middle-class Bengali elites, especially those joining the professional ranks or the civil services, occupied this nascent subjectivity. Thus, their experience forms one of the earliest traces of this negotiation—where colonial technologies were adapted, imitated and refashioned by a colonised group in Asia.

A cabinet-sized portrait of Sarala, the fourth daughter of RC Dutt, with her husband, JN Gupta, 1895. Among the cultural and social elites of Anglophile Bengali society, Dutt had followed Satyendranath Tagore’s example of entering the prestigious but exclusive Indian Civil Service. Newly (and colonially) established patterns of aspiration and self-fashioning were foregrounded in these early photographs. (Image courtesy of Malavika Karlekar.)

This class of people perhaps most visibly included writers and bureaucrats like Romesh Chunder Dutt, Toru Dutt and her sisters, as well as Rabindranath Tagore along with his extended family. With the growing popularity of cartes-de-visite, most middle-class families would have a photograph made that announced their presentation to the public sphere—much as a calling card or a formal memento. Here, nuances of body language, sartorial choices and acts of looking could determine a world of social differences (whether those between Anglicised Indians and nationalist Indians, or orthodox, caste Hindus and Brahmos, for example) and cultural aspiration. Apart from conjugal couples or staid government servants, photographs were also made of children along with several props like toys, or other properties that were usually provided by the studios. For instance, they often provided backdrops that ranged from monochromatic, impassive screens to painted, oriental images which were employed either at their discretion or on the orders of the client involved. These photographs were then preserved, displayed or exchanged among the local population as well as between them and their British friends in London or elsewhere. Thus, in a letter to a friend made in Cambridge, Toru Dutt sent and received their “likenesses” and wrote: “I will send you three different views taken of our Garden House (bagan bari) and Garden at Baugmaree (Bagmari)… Our Calcutta house has also been photographed, but the photograph has turned out to be such an ugly one that I do not care to send it.”

Aru and Toru Dutt, 1871. Reared in the illustrious Dutt family, they grew up writing and translating fiction and poetry in English and French. They travelled widely and corresponded with friends across Europe. As early literary cosmopolites of the colonial world—whose sensibilities were primarily shaped by their encounter with colonial discourses of European culture—it was inevitable that they would encounter the practice of photography in their daily life. (Image courtesy of Parvati Wadhawan, New Delhi.)

The photograph presented an aspect of the visible self that was closely curated, partially assimilated (to Victorian sensibilities) and actively involved in crafting the image of new Indians as colonial moderns—who were as much subjected by alien norms as willing to put up a traceable resistance to such norms of presentation.

Early photographs were also documents of contemporary fashion, registering the new changes that were being introduced to women’s fashions by women like Jnanadanandini Debi—reflecting a creative mode of adapting styles from across Indian cultures as well as the colonial Anglosphere. (Images courtesy of Rabindra Bhawan Photo Archives, Visva-Bharati University, Santiniketan.)

To read more about early photography in colonial India, please click here, here and here.

All images from Re-visioning the Past: Early Photography in Bengal 1875–1915 by Malavika Karlekar. New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2005. Supported by India Foundation for the Arts. Images courtesy of the author and Oxford University Press.