A Tree at the End of the World: Salomé Jashi’s Taming the Garden

A tree is transported across the sea to be transplanted in Ivanishvili’s private garden.

Quietly cryptic in its cinematic absurdity and beatific slowness, Taming the Garden (2021) is a film by Georgian filmmaker Salomé Jashi that builds the strange story of a Georgian billionaire who collects trees from the countryside for his own private garden-island. These trees—age-old beeches and acacias—are extricated from homes and shared spaces within the community, travelling miles over land and sea, as they leave in their wake the detritus of their removal and the shattering of intergenerational associations. Folkloric in its unravelling, the film asks how we define ourselves in relation to what exists around us, raising questions about humanity, ecology, sociality and wilderness. Described in her bio as “minimalist, poetical, sensitive and rough,” Jashi’s approach to filmmaking delves into the environment as a fathomless spatiality constituted of a recklessness that complicates our coexistence with nature. Taming the Garden positions an intersection of need and want that plays out across the subtleties of class and capital, artfully defining the act of uprooting as a haptic prolonging.

Residents work on extracting a tree in the countryside. The detailed process of digging the tree out involves heavy-duty drills and pipes as well as hours of manual labour.

In the film, we are taken through the mundanities of life in the Georgian countryside, which is suddenly marred by the extravagance of one man’s defiance and eccentricities. Jashi avoids obvious allusions to the extent and consequences of greed as well as the luxuries of whim, allowing viewers to see for themselves the brutality at the heart of this film. The visibly painful process of extracting these trees is immensely labour-intensive, and the camera follows in measured gestures the heavy machinery and load-bearing transportation required to carry these trees to the sculpted landscape that awaits them. Bidzina Ivanishvili, the former Prime Minister of Georgia and the richest man in the country, is responsible for this theatre of the grotesque. He remains unseen but present throughout: conversations in the dimly lit interiors of homes lead to arguments about whether the promise of better infrastructure should cost them a forest, rumours about his fortune—both financial and futuristic—are passed along as residents watch his actions tear through their carefully tended orchards.

After extricating the tree with its root system, it is transported on massive platforms, hoisted on trucks and rolled through the roads. On the left, one of film’s stationary shots frames the process of moving a giant tree in the darkness, its branches illuminated by headlights and flashlights, abrading wires and other trees in its path.

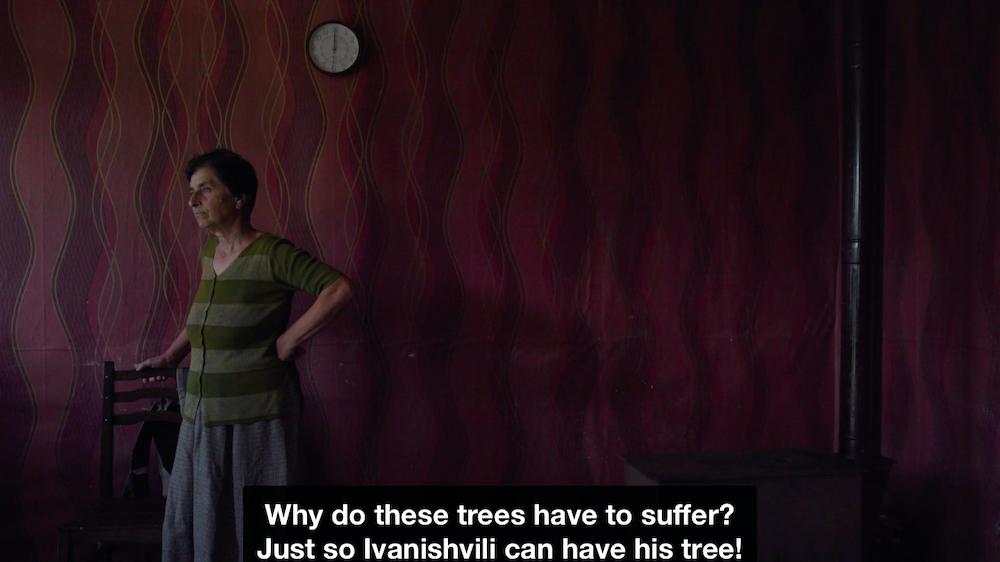

With breathtaking imagery, Jashi, cinematographer Goga Devdariani and sound designer Philippe Ciompi manage to convey an onomatopoeia of the act of uprooting. In scenes from the film, textures of sound take precedence: groaning branches stretch and pull with ubiquitous birdsong as trees are moved along narrow roads, metal pipes gurgle and hiss as they are inserted into mounds of earth around the base of trees, and idle chatter attempts to make sense of the imminent upheaval ripping through the fabric of the community. Sounds of the land are imbued with a mechanical hum, almost ambient in its suffusion. As the film sets aside any voiceover or narrative input, snatches of conversation further illuminate what are possibly a shared ethics of belonging, perspectives on jealousy and a common indignation at this specific kind of disruption, that is, a single-minded preservation of the self. As vestiges of history and memory, these trees sheltered both life and livelihood, and as we follow the path of the last tree, a dirge-like procession forms and a reluctantly compliant witnessing unfolds. As a couple watches a tree being felled, an older woman weeps softly, comforted by her fellow onlookers—a community realigns itself.

Residents walk behind a tree being transported to Ivanishvili’s private garden.

A tree reaches the shore, having crossed the Black Sea to Ivanishvili’s private garden.

Foregrounding a fragmenting countryside, the film establishes the incessance of that which is forcibly made temporary. In the drive towards development and definitions of progress, the powerful continue to vanquish environments and ecologies. One reads into Jashi’s tactful filmmaking a study of the image that delves a genealogy of care: what do we, as a society, lean on? What is a landscape, how do we visualise it, and who tends to its expanse? Taming the Garden is crafted with an ambivalent tranquility and an urgent appeal to the centrality of carework as commons.

A couple watches as Ivanishvili’s commissioned labourers cut down a tree in a private compound.

Conversations between residents shed light on their interpersonal confusions about Ivanishvili’s intentions and the ludicrousness of the situation as they mourn the loss of these well-loved trees that were familiar landmarks for the community.

Taming the Garden is screening online till the 14th of November as part of the Dharamshala International Film Festival.

All images from the film Taming the Garden by Salomé Jashi. Georgia, 2021. Images courtesy of the director.

To read about some of the other films at the festival, please click here and here.