Revolution in a Family Album: Firouzeh Khosrovani’s Radiograph of a Family

“Mother married father’s photograph.”

Tehran-based filmmaker Firouzeh Khosrovani’s Radiograph of a Family (2020) opens with these lines pronounced by a narrator, and a haunting moving shot of a mostly empty room, with some furniture covered in ghostly white sheets surrounded by empty walls. This is a site that we return to in the film constantly—an architectural model of her parents’ home in Tehran—a place to visualise and process their altering lives. The shot shifts to sepia-toned photographs of a decadently dressed bride at her wedding with family and friends. And indeed, propped up next to a bouquet of flowers is a stand-in photograph of her husband, who was not able to make the wedding due to commitments at work abroad. Here, already, the viewers encounter the centrality of the photograph in the family album as prompts for the narrative of the film—both in terms of the content of the images, and their materiality as objects that contain memories and histories.

This story is the filmmaker’s personal foray into the shared lives and experiences of her parents—in Iran, in Switzerland and then back again in Iran—reconstructed through fragments of family photographs and videos from public archives. Fictionalised dialogues narrated by actors animate the photographs along with slow, intimate tracking shots of the still images. Khosrovani situates the larger turbulent political moment in Iran during the Revolution of the late 1970s within and through her family archives, where we witness the manner in which the “Revolution entered our house” and penetrated the personal photographs of her parents.

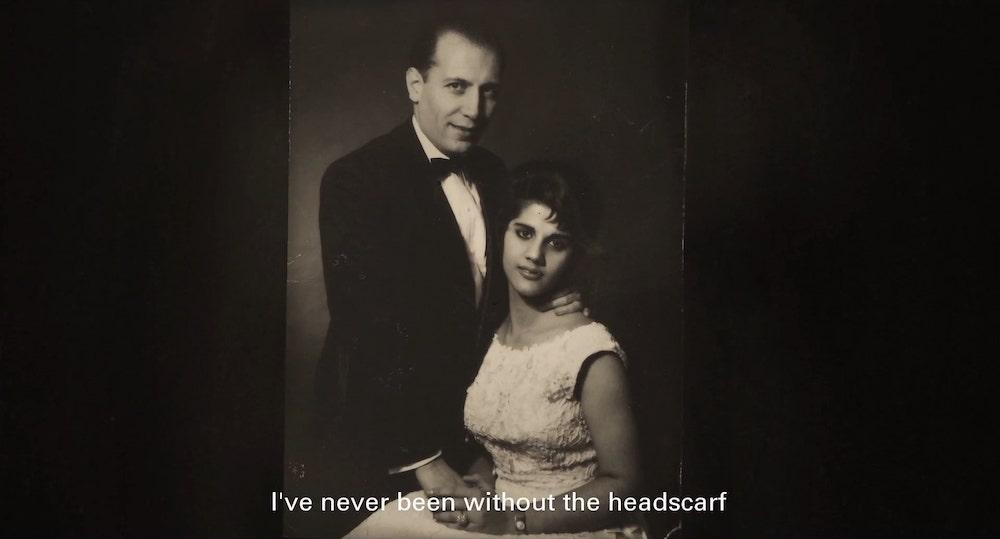

After marriage, Khosrovani’s mother Tayi, shifted to Geneva to be with her husband. Hossein was a secular, progressive man studying radiology, who loved classical music and the company of his international friend group. Tayi’s arrival itself is the onset of her alienation. Through the use of public archival videos combined with home footage, we encounter the conviviality in bars and on the streets that had swept Europe after the Second World War. These images and videos of people dancing, smoking and wandering are overlaid with Tayi’s trepidation—her fear of godlessness, of loss, and the awareness that “she never felt at home.” One of the most powerful scenes in the film is put forth through a photoshoot of the couple at a local studio, where we learn that Tayi’s husband requested, and later insisted, that she remove her headscarf. She could not say no, and the image symbolises all that Tayi resisted and yet found herself bound to—an image of herself that she could not recognise or reconcile with.

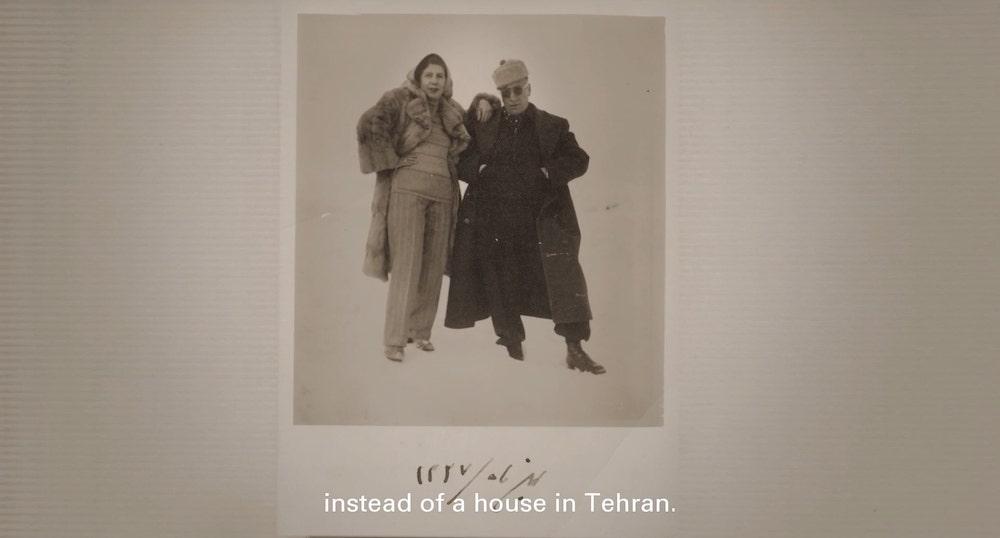

In another revealing scene that is mediated through photographs, Tayi looks at her husband’s carefully documented childhood and teen years in his family album. Confronted with the openness with which his female cousins swam in the sea and how they dressed in public spaces, she comments, “It was as if we lived in two different Irans.” It was after she encountered these albums, that she became resolute and inconsolable—they had to return to Iran.

After Tayi becomes pregnant (with the filmmaker), she holds her husband accountable to his promise that they will shift back to Iran, and the family photographs are set again in Tehran. There are tender moments captured: of Khosrovani’s birth and early childhood, birthdays and family picnics. The site of the house comes to be decorated with paintings and furniture, as the tumult gradually creeps in. Tayi sets out on a journey to find her own identity as she joins (and later becomes a leading figure in) the movement that leads to the Iranian or Islamic revolution—which removes the Pahlavi dynasty. Tayi dawns her headscarf again,which she had let go of in Geneva and in the early days of her return, and in a poignant scene with the piercing sounds of tearing paper, we are told that she destroyed all the photographs in which she was unveiled, erasing her past and destroying evidence of a dissonant, distant self. The images increasingly contain her and her friends in the movement, as they are militarised. We see photographs and footage of the women in their billowing burqas practising the firing of shells to participate in the Iran-Iraq war that followed the revolution. In parallel sequences, the interiors of the model of their home is transformed—at first containing all the elements of modern-day Western influences and joint conjugality, then slowly shifting to separation, and the tremors of air raids.

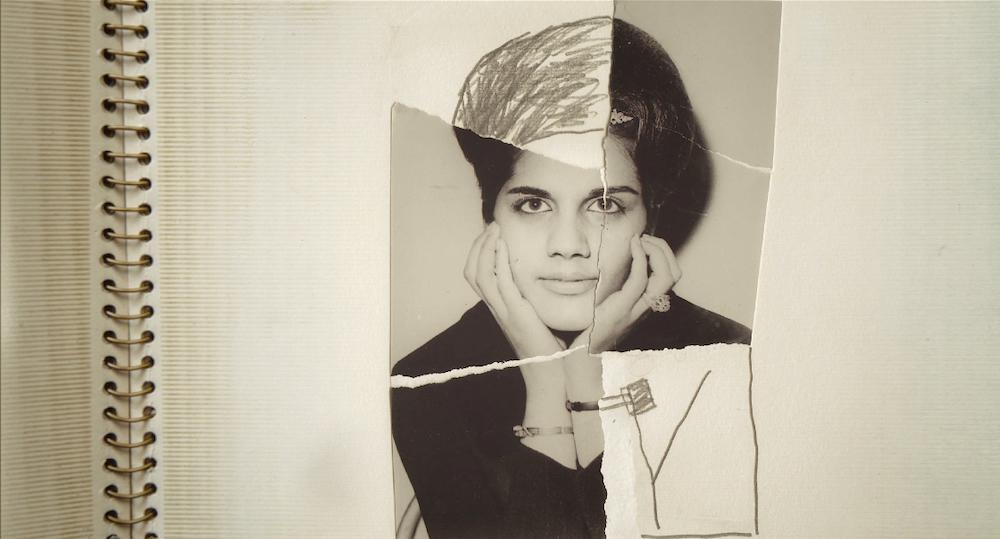

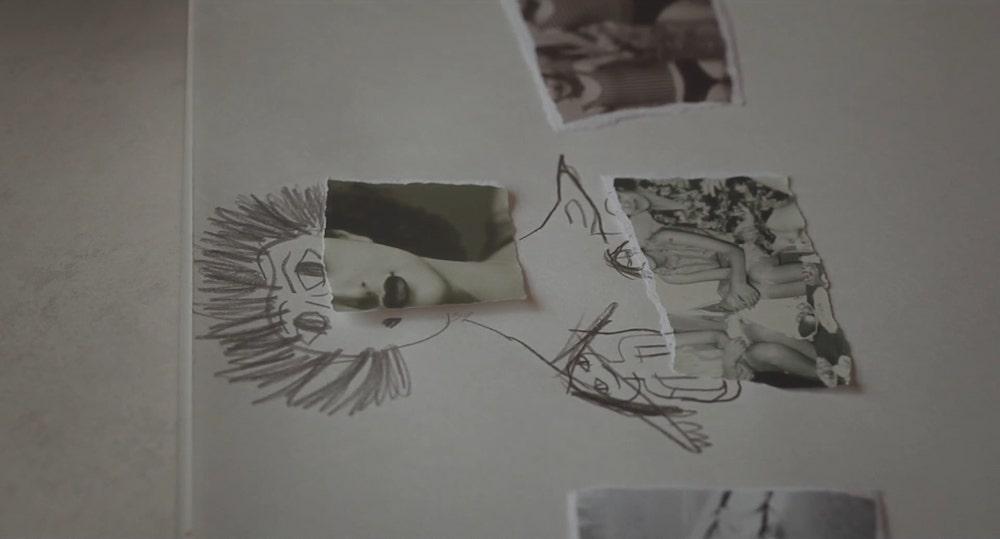

After Tayi cuts up her photographs, we see the filmmaker featured as a young girl going to collect the detritus and remains thrown in the trash. She takes them to her room and begins sticking the images in her sketchbook, completing and joining them—in an attempt to rescue and to reconfigure—blending the documentary photograph and the fabulated drawing. This creative act from her childhood is also the form of her documentary, where she assembles varied materials to tell a story, and turns her lens to relook at and reconstruct. Much like her father’s work with X-rays through radiographs, the filmmaker’s remembrance is a probing and inventive gaze at her family’s past and, through them, Iran’s recent history.

Radiograph of a Family is screening online till the 14th of November as part of the Dharamshala International Film Festival 2021.

All images from the film Radiograph of a Family by Firouzeh Khosrovani. 2020. Images courtesy of the director.

To read about some of the other films playing at the festival, please click here, here, here and here.

.jpg)